John Milbank argues in his Beyond Secular Order that “historicism cannot straightforwardly be considered as something specifically modern” (8).

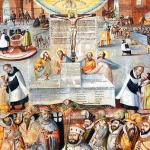

In fact, it originates from a Christian insight: “the sense of estranged distance from the past is initially the fruit of the Christian contrast between old and new covenants and with the pagan world. Even the Renaissance sense of a loss of pagan glories is not unanticipated by Patristic accounts of the general decline of the human race and the way that pagans often put contemporary Christians to shame. Partly for this reason, the first attempt to ‘re-gather’ pagan wisdom was made as early as the Anglo-Saxon period in England, and this impulse was then sustained through the influence of the Englishman Alcuin at Charlemagne’s court in the tenth century and in various monastic and cathedral schools in the twelfth” (8).

What we often think of as historicism – the Renaissance attempt to recover the past or the Enlightenment breach with the “Dark Ages” – is in fact the opposite: “The sense faintly present later on in ‘the’ Renaissance and then more emphatically in the Enlightenment of a distance of the modern world from a superstitious and benighted past cannot be considered to be fully fledged historicism . . . because it is more a celebration of a final exit from historicity” (8).

In the sense Milbank uses the term, “history” doesn’t refer to the deliverances of academic historians but the to the “lived history of memory and non-identical repetition” that sustains the common memory of a society.

This isn’t mere memory of facts otherwise established an known. Rather, Milbank argues, “enacted events have imaginative and theoretical horizons, then even the ‘facts’ of what has occurred only get clarified in the light of later re-enactments and later recallings. To say that these can ‘falsify’ is true, but superficial; more fundamentally they alone establish the truth of the occurrence of what has occurred. There can be no storming of the Bastille as a historical event (as opposed to a clashing of material atoms) without its annual commemoration, as Péguy famously concluded” (8).

From this perspective, the medieval world elaborates the patristic outlook, which was already incipiently historicist: “the Middle Ages, both as a traditional culture and as a Christian culture rooted in a commemorated event of rupture with an older past, were latently historicist through their activist account of memory and thought” (9).