Enlightenment secularism is committed to “freedom” as its overarching value. In an address on “Freedom and Truth” (published in The Essential Pope Benedict XVI), Benedict XVI describes the Enlightenment as a “will to emancipation” (citing Kant’s sapere aude).

Kant’s plea for philosophical freedom has political dimensions. According to the Enlightenment, critical reason will free us from the burdens of authority (341). Ultimately, the Enlightenment’s dream of freedom is Marxist, the dream that we can desire anything and also have the opportunity to carry out that desire. For the Enlightenment, “our own will is the sole norm of our action” (338). (Like Radical Orthodoxy, Benedict recognizes that this has Christian roots, in medieval voluntarism.)

In a word, freedom has been detached from truth that might guide, limit, tether it. This isn’t accidental. For the secular Enlightenment, “truth” is what we need to be freed from, since truth is limiting. Benedict brilliantly argues that this conception of freedom is internally contradictory and can only result in the opposite of freedom.

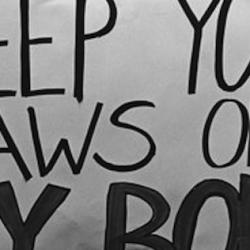

He begins with a discussion of abortion. Abortion must be legal, it is said, so that women can make decisions about their own lives. Benedict raises the obvious question: “Is she not deciding precisely about someone else – deciding that no freedom shall be granted to another and that the space of freedom, which is life, must be taken from him, because it competes with her own freedom?” (346).

The unborn child can only survive by physical union with the mother, yet the unborn child is genuinely other than the mother. For the child, “to be oneself in this way is to be radically from and through another.” The child is with the mother and this “being-with” places an obligation on the mother. She must “become a being-for, which contradicts her own desire to be an independent self.”

Even after the child is born, he or she remains dependent, a being-with who is dependent on the mother’s willingness to take the responsibility of being-for. And this structure of dependence and obligation remains throughout life: “Even the adult can exist only with and from another, and is thus continually thrown back on that being-for which is the very thing he would like to shut out” (346).

For Benedict, the unborn child is only a special case of what is generally true. The child in the womb is “simply a graphic depiction of the essence of human existence in general” (346; emphasis added).

Ultimately, this is the truth, an anthropological truth: “Since man’s essence consists in being-from, being-with, and being-for, human freedom can exist only in the ordered communion of freedoms” (352). This anthropological truth is rooted in theological truth, the truth of the God who is Trinity: “The real God is by his very nature entirely being-for (Father), being- from (Son), and being-with (Holy Spirit)” (347).

When our laws and institutions are detached from this truth of man and God, they cannot promote genuine freedom. They promote the pseudo-freedom of the will to emancipation.

The Enlightenment aspiration to liberate freedom from the truth of man is a latter-day expression of the original Adamic aspiration to be as God, to be “totally free, without the competing freedom of others, without a ‘from’ and a ‘for.’”

To be free is to be self-created. Perhaps with a nod to Milton, Benedict concludes that “this god that we aspire to be is not God but a devil” (347).

Notice what has happened here: Human being are created in the image of a God who is being-from, being-for, being with. The truth about man is that we are set in a network of relations and a “communion of freedoms.” In aspiring to be liberated from this communion and obligations it entails, the Enlightenment aspires to be free of humanity.

The attempt to be radically free becomes an aspiration to be free of humanity, free of myself. Enlightenment freedom ends in unfreedom. Radical secular humanism inverts into anti-humanism.