The following is an excerpt taken from my Blessed Are the Hungry (Canon, 2000).

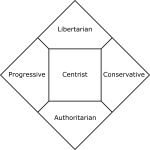

The Lord’s Supper is the world in miniature; it has cosmic significance. Within it we find clues to the meaning of all creation and all history, to the nature of God and the nature of man, to the mystery of the world, which is Christ. It is not confined to the first day, for its power fills seven. Though the table stands at the center, its effects stretch out to the four corners of the earth.

For centuries, theologians have attempted to explain “what happens in holy communion” by employing philosophical concepts—derived from Aristotelian or existential-personalist or some other philosophical tradition—or, more recently, by using models from the social sciences. In many ways, these efforts (framed in what theologians call “second order discourse”) have been illuminating and have contributed to a fuller practice of the Supper.

But such efforts give the illusion of moving beyond the “naive” outlook of Scripture to the more “fundamental” reality of the sacrament. I have written out of the contrary conviction that the Scriptural descriptions of the Supper are the most fundamental possible descriptions, though they may be elaborated (carefully) using extra-biblical concepts.

To the question, “What happens in holy communion?” my first answer is thus not “The whole substance of the bread and wine is changed into the substance of the body and blood of Jesus”; nor “We enter into the divine present where the past event of Jesus’ death is eternally re-presented”; nor “We have a personal encounter with the risen Christ through the medium of signs”; nor “We move ritually through a liminal moment of communitas toward the renewal of differentiated community.”

Some of these expressions are, I believe, simply wrong, but even if they were all perfectly correct, they would get us no closer to the base reality of the Supper than the variety of biblical descriptions.

What happens in holy communion? I wish to say: “We, as children of Adam, are offered the trees of the garden; as sons of Abraham, we celebrate a victory feast in the King’s Valley; as holy ones, we receive holy food; as the true Israel, we feed on the land of milk and honey; as exiles returned to Zion, we eat marrow and fat, and drink wine on the lees; we who are many are made one loaf, and commune with the body and blood of Christ; we are the bride celebrat- ing the marriage supper of the Lamb, and we are also the bride undergoing the test of jealousy; at the Lord’s table we commit ourselves to shun the table of demons.”

The claims made in the first paragraph above may be defended from two angles, one soteriological, the other eschatological. The soteriological argument is this: At the heart of our redemption is our union with Christ in His death, resurrection, and ascension. We are justified by union with Christ’s resurrection, adopted in the Son, made alive together with the One whom the Father raised from the dead, sanctified by the indwelling presence of Christ through His Spirit, made priests and kings in the Priest and King. In whatever way we wish to describe our redemption, we are describing some aspect of our union with Christ (see, further, chapter twenty-seven).

And this is precisely the soteriological meaning of the Lord’s Supper: “Is not the cup, which we bless, a communion in the blood of Christ? Is not the bread, which we break, a communion in the body of Christ?” (1 Cor. 10:16). If these two things are true—that union with Christ is the fundamental reality of our salvation and that the Supper is communion with Christ—then the Supper must mean everything that union with Christ means.

The Supper is a ritual sign of our justification, for in it God shows that He considers us righteous, i.e., table fellows and covenant- keepers; it is a sign of our adoption, for we are given food by our heavenly Father; through bread and wine we are joined to the power of the risen Christ, who is present in and through His Spirit; in the Supper we are raised to heaven to feast on Christ, enthroned in heavenly places, admitted to the holy place to eat sacred bread. The significance of the Supper is as high and deep and wide as salvation itself.

Further, Jesus is the climax and recapitulation of all re- demptive history. He is the victorious Seed promised outside the gates of Eden, the miracle Child of Abraham, the true Israel, the Prophet greater than Moses, the Priest after the order of Melchizedek, great David’s greater Son. The whole history of Scripture is the history of Christ Jesus, and in the Supper we are inserted into this Christ and this his- tory. Redemptive history came to a climax when the Father sent the Son who gave Himself as the bread from heaven, for the life of the world.

Therefore, the meal in which we feed on Christ is the climax of salvation history. To put it yet another way, the Bible is about the totus Christus, the whole Christ, Head and Body. Since the body of Christ is formed as body at the table, the whole Bible is about this meal.

The eschatological argument is this: Scripture teaches that the final order of things will be the kingdom of God, and Jesus consistently described the kingdom of God as a place of feasting. Better, the kingdom is not a place where feasting occurs, but the feast itself. The trajectory of human history was set at the cross, and it has been set to this one end: That the elect may feast forever in the presence of God.

At the Lord’s table, we receive an initial taste of the final heavens and earth, but the Lord’s Supper is not merely a sign of the eschatological feast, as if the two were separate feasts. Instead, the Supper is the early stage of that very feast. Every time we celebrate the Lord’s Supper, we are displaying in history a glimpse of the end of history and anticipating in this world the order of the world to come.

Our feast is not the initial form of one small part of the new creation; it is the initial form of the new creation itself. And this means that the feast that we already enjoy is as wide in scope as the feast that we will enjoy in the new creation. That is to say, it is as wide as creation itself.

Therefore, Lord’s Supper is the world in miniature; it has cosmic significance. Within it we find clues to the meaning of all creation and all history, to the nature of God and the nature of man, to the mystery of the world, which is Christ. It is not confined to the first day, for its power fills seven. Though the table stands at the center, its effects stretch out to the four corners of the earth.