In his monograph on Aliens in Medieval Law, Keechang Kim notes that the distinction of citizen and “alien” replaced the earlier binary of “free” and “unfree” during the later middle ages.

He cites John Fortescue’s De laudibus legum Anglie (c. 1468-70), which argued that “”Hard and unjust (crudelis), we must say, is the law which increases servitude and diminishes freedom, for which human nature always craves; for servitude was introduced by man on account of his own sin and folly, whereas freedom is instilled into human nature by God” (5).

He elaborates: “Unfree status was already viewed as contrary to nature by Roman jurists of the Classical period. Nonetheless, it was wholeheartedly accepted as provided by ius gentium. But Fortescue was raising moral doubts not only against the unfree status as such, but also against the law which institutionalised it (‘crudelis’ . . . lex). Such an attack certainly explains the disapproval and eventual demise of the legal approach which relies on the division between the free and the unfree status. Undoubtedly, legal reasoning was to move along the path leading to the notion of equality” (5).

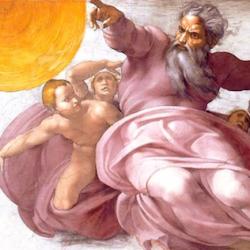

For Fortescue, this shift was related to an anthropology and a conception of political society: “men were viewed as ‘bundled up’ in units. Each such unit was portrayed as a mystic body, of which the king was the head.” Kim quotes Fortescue’s comment that “Just as from the embryo grows out a physical body controlled by one head, so from the people is formed the kingdom, which is a mystic body governed by one man as the head,” adding that “the law (lex) was responsible for the internal cohesion and unity of the mystic body of kingdom” (5).

In Fortescue’s own words, “The law, by which a group of men is made into a people, resembles the nerves and sinews of a physical body, for just as the physical body is held together by the nerves and sinews, so this mystic body [of people] is bound together and united into one by the law, which is derived from the word ‘ligando‘” (5-6).

This concept of the people as a mystical body, bound up with the notion of “ligeance,” appears repeatedly in the legal theorists that Kim analyzes. According to the law De natis ultra mare, “if both parents are ‘de la ligeance du Roi‘ when their children are born ‘dehors la ligeance le Roi,’ those children shall henceforth have the inheritance ‘deinz la dite ligeance‘” (141). The children are spatially dehors because they are born in another country; yet the ligatures of faith and allegiance that bond their parents to the king also bind the children, albeit at a distance.

As Kim explains, the notion of the kingdom as a mystical body lies behind this: “The realm has ceased to be a mere locus which is populated by people whose personal legal status is widely but justly different. The mysterious power of ligeance would homogenise the legal status of people ‘within’ it.”

Kim knows that the concept was borrowed from ecclesiology: “everyone of the medieval Christendom was thoroughly familiar with a parallel claim that the membership of the mystic body of Church was the key to obtaining the salvation (ultimate liberty) through Our Lord, of whom ‘our lord the king’ was the earthly deputy.”

By “tactful manipulation of terminology,” jurists found they “could demolish the thin dividing line between spiritual and temporal liberty. With the new use of ligeance, our lord the king could truly fulfill his mission in this earthly kingdom by graciously (gratiis) dispensing liberty, temporal as well as spiritual, to all those who are ‘within’ his ligeance, ‘within’ the mystic body of which he is the head. From then on, by engaging oneself within the bond and bounds of faith and allegiance of our lord the king, one would obtain liberty, spiritual and temporal” (142).

Robert Heimburger (God and the Illegal Alien, 43) is doubtful that the “mystical body” concept plays the role that Kim suggests, and doubts that it’s linked to allegiance in the ways Kim suggests: “His only source on the mystical body is the Fortescue passage . . . where Fortescue does not speak of faith and allegiance.”

That may be the only passage Kim cites, but he’s right to flag Fortescue’s usage. As de Lubac and William Cavanaugh have pointed out, the shift of “mystical body” from the Eucharist to the church to the kingdom is one of the subterranean sources of modern politics.

Kim, though, shows that the intention behind the political usage was humane. It expressed a conception of authority that did not rest on sheer power: “The sublime ideal repeatedly professed by Christian kings of medieval Europe was that their authority did not come from the sword, nor from the law, but from the faith. Ideally, their subjects should obey them not out of fear, nor out of harsh legal constraints, but out of faith. Precisely, it was this bond of faith which bound together the ruler and the ruled in a mystic body (corpus mysticum) within which subjection and liberty were curiously intermingled” (171).

It also elevated inhabitants of a realm so that all shared in the status of “insiders.” By the older definition, some of a king’s subjects were “unfree”; but by the later conception, they are all members of the king by being members of his mystical body. Echoing the rhetoric of Reformation polemics (deliberately?), Kim observes that “Only when law is truly grounded upon faith, can liberty be freely (gratiis) delivered to everybody in the name of law. Of course, ‘everybody’ here means an exclusive category of those ‘within’ the bond of faith: that is, everybody within the mystic body” (195).