George Landow argues (Victorian Types, Victorian Shadows) that the poetry of Gerald Manley Hopkins would look less bizarre, though no less innovative, if we placed Hopkins more firmly in the poetics of his time. Which is to say, placed him in the context of a typological poetics.

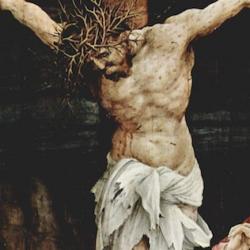

Hopkins’s “entire conception of inscape and its relation to the structure of a poem seems to develop from a mind accustomed to seeking types and figures of Christ” (7). Landow cites “The Windover” as an illustration of the method: Hopkins “elaborately presents the senuous, visible details of a really existing thing – here the hawk – and then makes us realize the elaborate Christian significance of each detail, as (like a type) the image of the bird is ‘completed’ only by reference to Christ” (7).

The typology is more explicit in the final lines:

No wonder of it: shéer plód makes plough down sillion

Shine, and blue-bleak embers, ah my dear,

Fall, gall themselves, and gash gold-vermilion.

Landow notes, “the basic of generating conceit of ‘The Windover’ is that higher beauty and higher victory come forth only when something – say, a hawk, an ember, or clump of soil – is subjected to great pressure and crushed or bruised” (7). Only when the hawk “falls” and “galls” does it “gash gold-vermillion,” bursting forth with greater glory.

The conceit is found also in “God’s Grandeur”:

The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed. Why do men then now not reck his rod?

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man’s smudge and shares man’s smell: the soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.

And for all this, nature is never spent;

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And though the last lights off the black West went

Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs —

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

The grandeur of God flames out when, gathered like an ooze of oil to its “greatness,” it is “crushed.” As Landow says, Hopkins alludes here to Genesis 3:15, a favorite passage of victorian preachers and poets; the crushed seed of the woman bursts with the grandeur of God. That “oil” is doubtless an allusion to the “christic” character of God’s glory, its focus on the glory of the crucified, the crushed Christ.

The hopeful second stanza also trades in typology. Commerce and toil have “bleared” and “smeared” a world charged with God’s grandeur, but “nature is never spent.” Hope for renewal doesn’t lie in some potency of nature but in what lives “deep down things,” the freshening Spirit, the Spirit who broods over the tired world as He did at the beginning, to make it new.

Or, we can read the stanza Christologically. Light fades in the west, but morning breaks in the east, the morning of Easter. Landow connects the brooding Spirit with the “crushing” of Jesus in Gethsemane (the garden of the wine press), the crushing that forces new glory into view.