Proverbs 22:2 says: “The rich and poor have a common bond, Yahweh is the maker of them all.”

The text has an immediate contemporary application. Rich and poor aren’t different species, and they shouldn’t occupy different spaces. But, in the U.S. at least, we’re “coming apart,” as Charles Murray has written, with the wealthy segregating themselves physically, socially, educationally. Solomon would be appalled at the neglect of our derelict inner cities; he would be equally appalled at the isolation of our gated communities. We have organized our social space in a way that denies the “common bond” that we have as creatures of Yahweh. We recoil at our own flesh (cf. Isaiah 58:7).

Several of the surrounding Proverbsfill out details of Solomon’s vision of a society that embodies the common bond of rich and poor. Proverbs 22:9 says, literally, that “The good (of) eye shall be blessed, for he gives from his bread to the poor.” Jesus also uses the image of the “eye” when talking about wealth: “If you eye is clear, then is your body full of light” (Matthew 6). The eye is an organ of judgment, associated with valuations, including valuations of wealth. The “dark eye” cannot evaluate the true worth of heavenly or earthly treasure, and so hoards treasure. Those with good eyes know the true value of earthly treasure, and also see the greater value the poor.

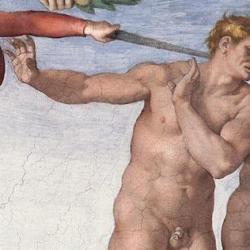

There is a connection with Genesis 3. The eyes of Adam and Eve were opened when they ate from the tree of knowledge of good and evil, a tree that signified kingly status and the authority to judge. By eating from the tree, they were elevated to a royal status for which they were unprepared. Proverbs 22:9 indicates kings with “open eyes” are generous. A good king is one with a good eye and a body of light. A good king discerns between good and evil, and provides for those who are in need. As always in the Bible, care of the poor is the criterion of a just society.

The Proverb says that the man with a good eye gives “from” his bread, or, as the NASB says, “some of his bread.” That might sound less than fully generous: Why doesn’t he give it all away? Is Solomon endorsing a residual selfishness? No. We should view this as a description of hospitality. The man with a good eye consumes his bread, but consumes it along with the poor. Hospitality, not unilateral dispossession, is the biblical ideal. Those who have should give to those who don’t have, but they should give in such a way that haves and have-nots share goods together. Economics is part of the larger “social” reality of fellowship. The common bond of rich and poor is expressed by common share in a loaf of bread.

From 22:22 through 24:23, Proverbs diverges from the typical two-line pattern. With a few exceptions, these proverbs run to at least two, sometimes several verses. Thus verses 22-23 form a single proverb, as do verses 24-25 and verses 26-27. Verses 28-29 go back to the normal pattern, but then the long-form proverbs resume in 23:1.

In 22:22-23 Solomon instructs his son in just treatment of the poor and afflicted. Proverbs is an instruction manual for princes. Solomon wants his son to rule justly. The “gate” is the place of trials and judgments, the place of entry and exclusion, and Solomon wants his son to establish justice among the elders of the gates. Rulers of the gates shouldn’t ignore the pleas of the poor nor favor the rich.

Verse 23 gives the rationale, echoing the warnings of the Torah (e.g., Exodus 23:6). Yahweh takes up the cause of the afflicted, and those who have no protector. He is Father of the fatherless, Husband of widows, Kinsman Redeemer of the oppressed. There is a lex-talionic justice at work: Yahweh threatens to “rob the soul” of those who rob the poor.

Of all nations, Israel should understand this. Israel was formed as a people when Yahweh delivered them from the oppressor – the Exodus. As Yahweh took up the cause of Israel in Egypt, He will take up the cause of the oppressed if Israel becomes an Egypt (as, ironically enough, it does under Solomon himself, and under Solomon’s son Rehoboam, perhaps the first recipient of these proverbs!). In Egypt, the Lord did “rob the soul” of those who “rob the poor,” taking the firstborn of Egypt in exchange for all the sons of Israel that were thrown into the Nile.

This is a portion of a post for Politics of Scripture. Continue reading here.