First, they came for the Confederate statues. But it didn’t stop there. Soon, the “woke” hordes were clamoring to tear down any statue of anyone who owned slaves. Then, anyone who had done anything that could be construed as racist. Eventually, every white historical figure, even those famous for fighting against slavery. And finally, activist Shaun King this week called for the removal of statues showing Jesus as a “white European.”

This, at least, is how conservatives are telling the story. In one Facebook group I’m part of, one of our more conservative members called on us to acknowledge the wisdom of one of the other members of the group, who had claimed all along that this was where the movement to tear down Confederate statues would lead. Indeed, many conservatives seem almost gleeful about Shaun King’s remarks. They confirm (allegedly) that, in fact, the BLM movement is an anti-Christian and “anti-American” movement. Over and over again, I’m seeing my conservative acquaintances proclaim, “It was never about the Confederacy.”

In other words, those of us who supported the removal of Confederate statues were, at best, “useful idiots.” We may not have intended things to go this far. But we should bow to our wiser brethren who knew, all along, that things would indeed go this far.

Descent of the Woke

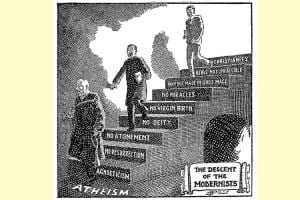

This rhetorical argument is yet another version of the time-honored “slippery slope.” Perhaps the most famous illustration of it is the cartoon “Descent of the Modernists” by E. J. Pace from 1924. In this depiction, liberal Christians descend inexorably from Christianity to atheism through steps that begin with denying the infallibility of the Bible and proceed to denying increasingly central Christian doctrines. (“No Deity” clearly means denying that Jesus was divine. And it’s interesting that this is above atonement, so that for Pace denying the atonement is a graver heresy than denying the divinity of Christ. But perhaps I read too much into the order of the steps. And at any rate I digress.)

According to Pace’s cartoon, someone who denies the infallibility of the Bible naturally moves on to denying more and more elements of traditional (Protestant) Christianity. And anyone who has grown up in conservative Christian circles has heard this kind of argument all the time. Ken Ham’s Creation Museum in northern Kentucky contains illustrations of devout Christians who became atheists as a result of believing in evolution. It also offers a scary urban wasteland which, we are to believe, is the social result of the theory of evolution. Deny Ken Ham’s version of “creation science,” and everything goes to hell. Literally.

It’s easy to mock many versions of the “slippery slope” argument. I remember the conversation in college in which my wiser friend Jonathan Huddleston debunked it for me. It was one of many small moments of liberation.

But obviously, movements and communities and individuals do, in fact, progress from one position to another that seems to them to follow from it. And often that progression leads toward a final result that most people would initially have found far too radical. We don’t have to rely on paranoid cliches about boiling frogs to recognize that the Overton Window does shift. And movements of social change contribute, deliberately or accidentally, to shifting it.

So if a “slippery slope” means simply that signing on to one position today may very well lead to signing on to a more radical one tomorrow, then slippery slopes do exist. Indeed, they are everywhere. We walk on an ever-shifting landscape of slippery slopes, tilting us this way and that. They may point to the “right” as well as to the “left,” and indeed to directions that don’t fit our rather stale political and ideological categories.

So how do we keep our balance?

I think a helpful starting point is to distinguish between different kinds of “slippery slopes.” I’ve come up with at least four.

Logical slippery slopes

First of all, there’s the logical slope. This is the slippery slope proper. We may hold ideas that do, in fact, have implications we haven’ yet fully worked out. As we think more deeply, we come to realize that our principles commit us to more and more radical conclusions. The interpretation of the Constitution held by Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass during the slavery debates, for instance, argued that the abolition of slavery was the necessary consequence of the principles embedded in the Constitution. Newman’s theory of development of doctrine (though it has its problems) argues that Catholic doctrine (and indeed any body of organized teaching) has a kind of “slippery slope” built into it. Over time, the Church comes to see more fully the implications of the original Christian revelation.

However, even here we should be very careful making claims about the implications of other people’s ideas. We naturally don’t understand the ideas of other people as fully as we understand our own, and if we are unsympathetic to them we are likely to caricature them. Furthermore, in fact none of us simply derive our beliefs from one single principle or a harmonious set of original principles. We are always navigating a complex set of ideas that pull us in many different ways.

So when we make claims about logical “slippery slopes,” we should be careful to phrase our claims modestly. It’s appropriate to say “I don’t see, given your premises, why you don’t conclude X.” And if, in fact, people do wind up concluding X, I suppose we can feel a little smug about it. But only a little. We should always be on the lookout for the tendency to make up straw-man principles and brilliantly derive other people’s actions and ideas from those principles.

Practical slippery slopes

A second kind of slippery slope, related to the first, is the practical slope. In this case, rather than having ideas whose implications we work out slowly, we have a practice that needs a justification. One disturbing example of this is the development of full-blown racial theory as a justification for the existing practice of enslaving people of African descent. 17th-century slavery, and even 18th-century slavery, was not rooted in racial ideology in the same way as 19th-century slavery. And the ideology has, to one degree or another, survived the practice that it came into existence to justify. It’s given rise to less extreme but still noxious practices. 21st-century white people justify the police profiling of African-Americans for essentially the same reasons that 19th-century white people used to justify their enslavement.

In some cases, of course, we may have one practice which many different people engage in for widely different ideological reasons. I think the destruction of statues is an excellent example of this. It’s a mistake to assume that everyone who does it belongs to a “woke” movement with a uniform ideology that will move in predictable directions. And of course the same is true for something like police profiling. In my previous paragraph, I fell into exactly the trap I’m warning against. Not everyone justifies it for the same reasons. We can’t always qualify our language to reflect this. But we should always bear it in mind and note it when appropriate. We should never assume that any group of people doing something we don’t like (or that we like, for that matter) are all doing it for the same reasons.

Psychological and social slippery slopes

A third kind of slope is the psychological one. We may tend to move from one position or action to another not because logical necessity compels us but because the same sorts of feelings and intuitions that lead us to think X will also eventually lead us to think Y. This is a “softer” slope than the logical one and we should always be careful about predicting other people’s behavior based on it. Even more than with logical slopes, there are all kinds of other factors that intervene. In the case of statue destruction, of course the same psychological impulses that lead a person to smash a statue of Jefferson Davis might lead that same person to smash a statue of Abraham Lincoln. Smashing statues is, I’m sure, fun and cathartic and if I got in the habit of doing it, I’d probably find it hard to stop too. (I did spray a statue of the Virgin Mary with a water hose when I was seven, but I have repented of that.) But that doesn’t mean there’s no way to approve of smashing one kind of statue without approving of smashing another. A psychological slope is not a logical one and we should not confuse the two.

And finally, there’s a “social slippery slope,” corresponding to the practical slope as the psychological slope does to the logical. Group movements take on their own momentum. Even if they don’t share all the same principles, the members of the group are prone to do what others are doing. People compete with each other to show their loyalty to whatever the key markers of group identity may be.

Standing firm on sloping ground

In the case of the statue-smashing movement, those of us convinced that Confederate monuments probably should be removed from places of public honor have no logical reason to agree that other monuments should also be pulled down. My own position is that if a monument has been raised to honor something good done by a person who also did evil, we should keep it. On that principle, there is no “logical slippery slope.” There is no doubt a social slippery slope–a pressure to show one’s “wokeness” by approving whatever seems the radical, iconoclastic thing to do at present. And it may well be that other people have more radical principles from the beginning.

If there are good reasons to pull down a statue of Jefferson Davis but not of Lincoln, or St. Louis, or whoever the target of the moment may be, then we need to have the courage to support the first but not the others. Doing so does not strengthen the hand of those who want to “pull down everything.” It weakens it. By standing firm for the approach that matches our principles, we create daylight between things that others, on both extremes, may wish to lump together.

The same is true for E. J. Pace’s cartoon. If I believe in the resurrection of Jesus because I believe in the inerrancy of a “commonsense” reading of Scripture, then denying the latter will lead me to doubt the former. But distinguishing between the reasons for believing in these two things weakens, rather than strengthening, the case for throwing them both out. Fundamentalists would have us believe that accepting evolution leads to atheism. But this becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

If you tell young people that they can’t accept mainstream science without rejecting the Faith, you are basically encouraging them to reject the Faith. You are tying the glorious truths of historic Christianity to a particular kind of modern literalism. And similarly, if you say that removing statues of Confederate heroes logically leads to a rejection of Western Civilization and Christianity, what are you saying about Western Civilization and Christianity? (Never mind the problems inherent in identifying those two things with each other.)

Pointing to the herd mentality that leads people to go from one kind of iconoclasm to another is itself just another kind of herd mentality. In an age of trends and fads, let us instead stand firm on principles. Let us pull down those statues that our principles tell us to pull down, and no others. And let us be willing to make a reasoned moral case for our choice both to those who wish to pull down fewer statues and those who want to pull down more.