This past Sunday, the Catholic lectionary juxtaposed two famous Biblical stories. In the Old Testament reading, we had the powerful and troubling story of Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac. Our Gospel reading, in contrast, was the transfiguration of Jesus.

By putting these stories together, the lectionary is inviting us to think about them in connection with each other. In both stories, a “beloved son” goes up a mountain. In both stories, there’s some kind of divine acknowledgment of a special covenantal role (Jesus as beloved son, Abraham as the one in whose descendants all the earth’s inhabitants will find blessing). And both stories involve, at least by implication, sacrifice. Jesus speaks to the disciples about his coming death and resurrection more clearly than ever before as they come down from the mountain. And in Luke’s version this link is more explicit. Moses and Elijah are talking to Jesus specifically about “his departure which he was about to accomplish at Jerusalem.” As commentators and preachers commonly point out, Jesus’ path off the mountain is a path to the Cross.

Obviously there are a lot of differences as well. Jesus goes up the mountain of his own accord, whereas Isaac is brought there by his father, not knowing what the purpose of the journey is. Jesus’ sacrifice takes place after he leaves the mountain rather than on it. While neither of them dies on the mountain, Jesus does, in fact, go through with the sacrifice. (So that in traditional Christian interpretation Jesus can be seen as both the perfect Isaac–the beloved Son offered in sacrifice–and the ram whom God provides as an alternative sacrifice in the Genesis story. Indeed, Christians traditionally see Jesus as the true fulfilment of Abraham’s evasive answer to Isaac that “God will provide a lamb.”)

Most importantly, Jesus offers himself willingly as a sacrifice. Some traditions suggest that Isaac also did so, but the Biblical text itself does not say this.

Divine child abuse?

This allegorical (or typological) way of reading the story is less popular among Christians than it used to be. Progressive Christians, in particular, are uncomfortable with appearing to legitimize the horrible literal sense of the story by allegorizing it. Indeed, a number of theologians (as well as non-Christian critics) have suggested that the connection between the two stories works the other way. If Jesus’ death is a sacrifice for our sins, then it is an act of “divine child abuse.”

I’ve heard some very good sermons on the sacrifice of Isaac from liberal pastors in the Reformed tradition. (Before getting a permanent gig playing the organ for a Catholic church, I was a substitute for a lot of local churches, including several Presbyterian and one Congregationalist one. And these gigs tended to happen in the summer, which is when the Revised Common Lectionary used by many Protestant churches assigns the sacrifice of Isaac.) These pastors wrestle with the text and treat it as an example of a “text of terror.” One of these sermons treated it (in part) as a kind of cautionary tale, asking why Abraham did _not_ question the apparent divine command.

I think this is a legitimate approach. We shouldn’t play down the horror of the story. And we emphatically should not use this story to promote the demonic “divine command theory” that says that our ethical principles are subordinate to what we believe God is commanding us. (We can of course be confident that no true divine command would be evil. But we can be surer that killing children is evil than that any specific impulse or apparent revelation is really a divine command.)

Myths of sacrifice

But I don’t think this critical approach should be our last word on the Genesis story.

Sacrifice is a widespread part of human culture. Its roots seem to lie deep in our collective experience of the sacred. There are of course a lot of possible explanations for this. One that has gained a lot of traction in certain Christian circles is Rene Girard’s “scapegoat” theory. Girard argues that sacrifice is a ritual that developed out of a primal event in which human beings blamed one person for their conflicts and expelled or killed that person, thus restoring harmony to their society. The ritual of sacrifice reunites this primal, mythic act of violence, with the sacrificial victim “bearing the sins” of the community.

In this interpretation, the sacrifice of Jesus is the “sacrifice to end all sacrifices” because it exposes the lie at the heart of sacrifice. Since Jesus is innocent, Jesus’ death “unmasks” the mechanism of sacrifice as a way in which we project our guilt onto someone else. This interpretation is in one way deeply traditional and orthodox, and in another overturns the traditional Christian understanding of sacrifice as something necessary to atone for sin.

I find Girard compelling in a lot of ways, but I don’t think think his account of sacrifice is adequate. It seems. in its own way, as reductionistic as a purely materialistic approach. (Seeing sacrifice purely as a way for elites to consolidate power, say.)

Sacrifice as communion

The root of sacrifice seems to be rather in the concept of communion–the intuition that life and its goods are a gift from the divine and that to honor the gift rightly we must invite the divine presence to share in those goods. Christianity has distorted our picture of sacrifice to some extent by making us prone to think of all sacrifice as a bloody act of atonement for sin. (Western Christianity does this more than Eastern and conservative Protestantism more than Catholicism.) But many acts called “sacrifice” around the world do not involve death or the shedding of blood. They may involve gifts of wine or fruit or flowers.

But many do involve blood. And understandably so. Because life as we know it is bound up with death. We live by feeding on other living things, and in the end we die and become the food for other living things in turn. It is death that reminds us most sharply that our lives are not our own. They are gifts from the Source of life from Whom we come and to whom we return.

The sacrifice of the gods

A particularly dramatic and gory example of a culture rooted in blood sacrifice is Mesoamerican culture, particularly Aztec. In Aztec mythology, each age of the world was created by a god who sacrificed himself in order to become the sun of the new world. In the most recent, fifth age, the god who sacrificed himself was the humblest and poorest of the gods. But by leaping into the sacrificial fire, he became the source of light and life for all creation. Aztecs sacrificed human beings to him, and to other gods, on a massive and horrific scale, believing that by doing so they were feeding the god who had sacrificed himself for them and thus allowing the universe to continue existing. They appear also to have engaged in ritual cannibalism of the sacrificed victims in order to commune with the gods.

From a Christian perspective, particularly a Catholic perspective, the Aztec practice was horrifically immoral but its mythological basis also contained profound truth. We believe that it is, in fact, the sacrifice of God that keeps the universe going. We believe that the one Creator became humble and poor and sacrificed himself for the life of the world.

The unbloody sacrifice

Where we part company with the Aztecs, of course, is in their belief that they needed to carry out continual bloody human sacrifices in order to continue the work of the divine sacrifice that had established the universe, or to eat the bodies of slain victims in order to commune with the gods. Furthermore, we can see how their mythological beliefs served to support (and inspire) their imperialistic violence, as it has done in many other cultures. (This is where Girard is clearly on to something.)

For us as Catholics, instead, the one sacrifice remains the sacrifice of Jesus, and that sacrifice is continually “re-presented” in the Mass. We don’t need to keep sacrificing ourselves or other people. Rather, we celebrate and share in the unbloody sacrifice of the Mass and we commune in the real, glorified Body and Blood of Christ. In this transfigured form of “ritual cannibalism,” we are transformed into Christ by eating the substance of his flesh and blood under the forms of bread and wine. We don’t consume others in order to give us power. We don’t worship a God who consumes us in order to feed his divine power. We worship a God whose nature is mutually interdwelling, self-giving love, and who makes that love known to us through the Incarnation, the Crucifixion and Resurrection, and the mystery of the sacraments by which we share in Christ’s saving acts.

But far too often we have acted as if bloody sacrifices were still necessary. The Spaniards who brought Christianity to Mexico and were (rightly) horrified by Aztec atrocities themselves practiced the ritual execution of heretics, often through burning them alive, as a way of purifying their society and affirming their orthodoxy. And they replaced Aztec imperialism with an imperialism of their own. And the modern secular order that has sought to replace both paganism and Christianity has created its own forms of bloody sacrifice.

The words of the Father on the holy mountain continue to sound in our ears: “This is my beloved son, listen to him.”

He offers us a way out of the economy of bloody sacrifice into the economy of indwelling love. But the choice remains: will we listen to him or not?

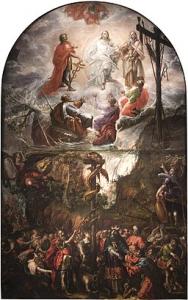

Image: “Moses and the Brazen Serpent and the Transfiguration of Jesus,” Cristóbal de Villalpando, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons