In a Facebook conversation a while ago, I made the claim that all the major religions reached their current form through a long and difficult process of rational inquiry. A number of people (presumably atheists) reacted to this with snarky comments about how ridiculous it was to ascribe “rational inquiry” to religious traditions. The most succinct response was: “A belief in talking snakes does not come [by] rational inquiry. Try again.” So I did. Here’s a longer and more developed version of my reply.

Was the snake ever just a snake?

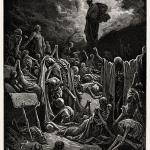

The crack about “talking snakes” presumably refers to the story found in Genesis 3, in which a talking snake persuades the first two humans to eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil. The story is part of the Torah, the five “Books of Moses,” most likely written in its present form roughly around 500 B.C. (OT scholar friends correct me if I’m misrepresenting the current consensus.) But the “J” strand to which Gen. 2-3 belongs may be older than that, and the story itself is most likely a folk tale that had been passed down in oral form for quite a while.

Are there any real literalists?

The long and winding course of the ancient serpent

The idea that the snake is Satan not only isn’t anywhere in Genesis, but isn’t anywhere in the Old Testament at all that I can think of. (Though to be sure there are various references to malevolent serpent/dragon-like beings.) It pops up in the Book of Revelation (12:9, 20:2) explicitly and is probably implicit elsewhere. (Romans 16:20 speaks of God crushing Satan under the feet of believers, which is probably a reference to Gen. 3:15; John 8:44 refers to Satan as a liar and a murderer from the beginning, probably an allusion to the serpent bringing death through deceit. 2 Corinthians 11:3 speaks of the serpent deceiving Eve and one can perhaps assume that Paul thinks of the serpent as identical with Satan and of Satan as the one he fears will deceive the Corinthians, but he doesn’t actually explicitly say so.

Since the Jewish tradition also identifies the serpent with Satan, one can assume that the interpretation has its roots in the Second Temple period. (Jewish theology about Satan is significantly different from Christian interpretations, though.) But it obviously resulted from process of inquiry into what the “animal fable” of Genesis 3 could actually mean. What kind of serpent could really cause death and labor pains to come into the world? Over the centuries, both Jews and Christians, in somewhat diverging ways, developed complex theological interpretations of Genesis 3 and its resonance for other parts of Scripture, and these theologies have (at least in Christianity) come to seem so obvious that many people simply assume this is the literal sense of the original text.

Three rival versions of inquiry: the seductive clarity of the Encyclopedia

Nearly all apparently “literal” interpretations have a similarly complex history. But why do we call this process “rational”? For many modern people, “rationality” implies an impartial, objective analysis unaffected by tradition and assumption. This is why so many atheists find it hard to acknowledge the rationality of religious inquiry, and why so many believers are unwilling to recognize the complex nature of the traditions that shape their own assumptions.

My use of the phrase “rational inquiry” is influenced by the work of Alasdair MacIntyre. In MacIntyre’s 1987 Gifford Lectures, Three Rival Versions of Moral Inquiry, published in 1990, he distinguishes between three different approaches to ethics (and by extension to rational inquiry more broadly). The first, the “encyclopedia” method, is characteristic of the Enlightenment. In this approach, truth is something objectively discernible by any rational person. People make mistakes because they are deceived either by their own flaws or by some corrupt external influence which biases their judgment. But all unbiased, reasonable people, looking at the same evidence, will come to the same conclusion.

Genealogy: the grubby roots of truth

The second approach, the “genealogy” method, is characteristic of Nietzsche and of much postmodern thought. In this view, there is no objective truth to be had. Truth claims are fundamentally rhetorical claims of power, and the proper response to such a claim is to unpack the history behind it, showing the contingent (and often disturbing) historical factors that resulted in people coming to believe in the claim. (Here’s one really influential example of this approach in action with regard to a highly charged contemporary issue.)

MacIntyre argues that both these methods are hopelessly flawed as general approaches to moral truth (or truth in general). The Encyclopedia method respects objective truth but is hopelessly naive about the possibility of anyone actually being entirely free from bias. And since people who hold to the encyclopedia approach see divergent views as errors resulting from the bias or corruption of the opponent, it’s hard for them to see where they might be seriously wrong. As MacIntyre argues at more length in his Whose Justice? Which Rationality? much Enlightenment thought took the thought habits of a particular group of British elites to be characteristic of human beings as a whole and thus constructed whole ethical systems that were really the projection of the interests and biases of a narrow section of humanity.

Tradition: truth through story

MacIntyre’s alternative is the “tradition” method. This approach acknowledges that there is a truth outside ourselves, but that we have no way of getting at that truth apart from a particular tradition. A tradition, for MacIntyre, is “an argument extended through time.” It’s not a set of beliefs or practices handed down unchangingly and accepted blindly. Rather, it’s a dynamic process of inquiry with certain parameters that have been worked out in a particular context as the appropriate ones for this particular inquiry. When new circumstances arise, a tradition may face a crisis because its methods and assumptions no longer work as well. But this also generates creative thinking, as adherents of the tradition seek to explain how a particular solution to the new problem makes sense of “the story so far” and explains the new challenges in light of that ongoing story.

I think this is by far the best way to approach questions of truth in general, but it’s particularly applicable to the history of Biblical interpretation. To be a “believer in the Bible” is not simply to believe that a particular text is true but to be part of a very long process of seeking to understand and apply that text. Stories that “don’t make sense,” often because they are removed from their original context, tend to generate particularly intense discussion. Thus, “problem” stories often become mirrors of changing cultural norms. They bridge gaps between generations and provide cultural continuity. This may not look like “rational inquiry” to people seduced by the specious clarity of the encyclopedia. But it is how the human race has historically carried out most of its inquiry into the meaning of life and death, and it is how most people continue to do so.

Michelangelo, Fall and Expulsion from Eden, public domain image from Wikimedia Commons.