In the shadow of Lent

Advent has always stood in the shadow of Lent. As the “other” season of fasting and solemnity and “paring back,” it has often been treated as a milder version of the Great Fast. In the Byzantine tradition, it is practiced for forty days like Lent, and Lent is often referred to as “Great Lent” with the implication that Advent (and the two other fasting periods of the Byzantine tradition) are lesser examples of the same sort of thing. (For reasons I’ll get into, this may not be as much of a problem in the Eastern traditions as it would be in the Western.)

In contemporary Western Catholicism, there’s been a laudable attempt to get Advent out from Lent’s shadow and emphasize its unique character. Indeed, Advent liturgical decisions in contemporary Catholicism are often embattled by discussions of whether a particular practice or even a particular song will make Advent “a little Lent.” (Conversely, one priest criticized me and the other layperson making song choices at our parish’s Spanish Mass for choosing a Lenten song that sounded too much like an Advent song.)

This year, for instance, I and the choir at our parish (where I’m the organist) discussed whether we wanted to use the chant Mass setting this Advent as we typically do during Lent. Would it make Advent too much like Lent? Or did restricting chant to Lent associate chant too much with penitence and mortification? In the end, we didn’t switch to chant for Advent, largely because the choir wanted to set aside some time to practice the chant setting and the organist, who is very much a part-time organist and has a new job this semester teaching Latin at a Catholic high school, never scheduled one. (Yes, that’s also one reason why it’s been so long since I’ve posted on this blog.)

What are we saved from?

These liturgical choices are fraught with a certain anxiety because, I think, we are all a bit hazy on what really makes the difference between Advent and Lent. For what it’s worth, I myself love Advent and would much rather make Lent a “big Advent” than Advent a “little Lent.” But I have nothing against Lent either. Each season, rightly understood, can I think enrich the other.

This Advent, I’ve been thinking about what really does characterize Advent as a unique season and distinguish it from Lent, at least Lent as we typically think about it in the Western tradition. And I think it’s this: Lent is primarily about repentance from sin. Advent, we always say, is about “waiting.” But waiting for what exactly? The salvation brought by Christ. But what is this salvation? The obvious answer is salvation from sin–which brings us back to Lent and repentance.

Death and corruption

In the Greek Fathers and the Eastern Christian tradition, salvation is often said to be fundamentally from death and “corruption,” with sin as one particularly vicious expression of that broader pattern of decay. Many of us in the West are seeking to recover that broader, more holistic understanding of salvation. And I think some of the “Lent/Advent” tension has to do with the discomfort many of us feel (for good reason) with the primarily moralistic “feel bad about your sins” approach that has often characterized Lent.

Salvation from death and salvation from sin aren’t, of course, opposed. They are concepts that depend on and illuminate each other. And Easter is certainly about salvation from death and not just from sin. (This is particularly emphasized in the Eastern traditions, which is why, as I suggested earlier, maybe treating Advent as a “little Lent” isn’t as much of a problem for them as it has been for us.) In the West, we begin Lent with Ash Wednesday in which we remember our mortality and not just our sinfulness.

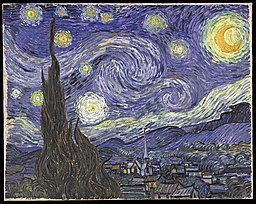

A time of darkness

And yet, I think Advent is uniquely able to reorient us to that broader understanding of the human condition and the salvation offered by Jesus. The overwhelming characteristic of Advent, in terms of our experience, is that it’s a time of increasing darkness. The days are getting shorter. The tooth of all-devouring time is felt more keenly. In the face of darkness and rain (or snow) and winter winds, we become aware of our fragility.

Lent, on the other hand, derives its very name from the word “lengthen.” It’s a time of longer days and increasing light. Somber though it is, it’s a time when the world around us is coming alive. This is one of the great beauties of Lent–it’s a time to tighten our belts and redouble our efforts as we march toward the great burst of light and life that awaits us, whose first rays we can already see and feel all around us in the natural world.

The helplessness of Advent

But in Advent we are helpless. We are tied to the wheel of the year rolling toward the darkness. Yes, we know that the light will return, just as, in spring, we know that the darkness will return. But our own experience (as opposed to the deliverances of the Faith) gives us little reason to be confident that our lives will follow the same pattern. At times of darkness like these, it is easier to say with Catullus:

soles occidere et redire possunt;

nobis, cum semel occidit brevis lux,

nox est perpetua una dormienda.

Or in Thomas Campion’s English rendering:

Heaven’s great lamps do diveInto their west, and straight again revive,But soon as once set is our little light,Then must we sleep one ever-during night.

Lent calls us to repent, which is hard. Advent calls us to wait and hope, which is even harder. Or, more precisely, it calls us to a form of repentance that is more about waiting and hoping than about doing anything. And it also offers us a different perspective on the sin from which we are called to turn.

Rebellion of the pitiful mammals

The Western approach to sin, since Augustine (and still more since the various reform movements of the late Middle Ages), has often been “you are a rebel and must submit to the rightful authority.” Growing up, I heard myself described this way many times. I was told that simply by virtue of being born I was in a state of rebellion from which only God’s grace could deliver me. My heart was “deceitful and desperately wicked.” By nature I hated God and hated goodness. Only by an agonizing process of repentance and surrender to God could I cease to be a person fundamentally committed to spit in God’s face in the service of my own sinful desires.

I’ve come to realize that this description simply doesn’t fit my experience. I don’t think that I have ever, to my knowledge, been the person my grandmother’s heavily Puritan-leaning version of Wesleyan theology told me I was. I experience sin not so much as rebellion but as weakness–a persistent tug toward death and darkness and decay, a helplessness that swallows hope. And yes, one of the temptations in the face of that all-encroaching darkness that flickers around the edge of my vision is to indulge in futile and absurd gestures of rebellion, to try to persuade myself that I’m really in control, to deny the darkness instead of confronting it.

The “rebellion” narrative of human sinfulness makes our sin more grandiose than it is. Our most notorious and obvious sinners–the great tyrants and mass murderers of history–are pathetic little mammals trying to deny the inevitability of death by making themselves the source of destruction. The much-quoted line from Breaking Bad, “I am the danger,” comes from a man whose whole story arc begins with a cancer diagnosis and the loss of his job.

Waiting in the darkness

Sometimes, in the face of our fragility, all we can do of any value is wait in the darkness. That is repentance–a turning from the acts of wrath that call wrath upon us. And it is an act of hope: that the God who made the stars of night will indeed be our everlasting light.