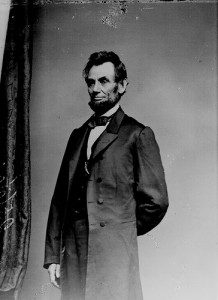

One of my favorite books is Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals, in which Goodwin reflects on Lincoln’s sagely leadership of a cabinet, many of whose members opposed both Lincoln and one another prior to Lincoln’s election and, at times, during Lincoln’s presidency, one of our nation’s darkest hours. With the future of the nation at stake, Lincoln creatively synthesized opposing factions, transforming polarization into contrast for the well-being of the United States.

One of my favorite books is Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals, in which Goodwin reflects on Lincoln’s sagely leadership of a cabinet, many of whose members opposed both Lincoln and one another prior to Lincoln’s election and, at times, during Lincoln’s presidency, one of our nation’s darkest hours. With the future of the nation at stake, Lincoln creatively synthesized opposing factions, transforming polarization into contrast for the well-being of the United States.

One of my teachers Bernard Loomer saw “size” or stature as one of the most important aspects of theological reflection. Loomer asserts that size signifies “the volume of life you can take into your being and still maintain your integrity.” No doubt, Loomer remembered words describing Jesus’ growth, “and Jesus grew in wisdom and stature.” Size invites us to embrace as much reality as possible, to see the possibility of partnership amid contrasting opinions, and to seek reconciliation with opposing forces. The concept of size or stature finds its foundation in the recognition that relationship, interdependence, and unity along with individualism and diversity characterize the nature of reality. Despite our differences in politics, theology, ethnicity, sexual identity, and values, we are ultimately “one in the spirit.” As Loomer asserted just two days prior to his death, “Unless you begin with unity, there is no way in which you can achieve a unified outlook on life. The intuition, the sense of unity, has to be there fundamentally. If it is there, then you can understand the various roles and parts in relationship to this unity. But if you don’t have the unity to begin with and you try to create a unity out of the parts, this never works […]. Once you have seen [the unity], you can divide life in various ways providing that the centrality of unity never leaves your mind […] The strange business is that once you have grasped the unity or been grasped by the unity, the fearsomeness is gone.”

Despite his flaws, Lincoln exemplifies the stature that is only rarely attributed to national or political leaders. The term “stature” eludes our descriptions of a good many religious leaders as well. But, today, stature is more important than ever. We live in a time of political gridlock, mirroring the violence of the culture and religious wars in our time. In politics, there is virtually no such thing as a “loyal opposition” to the President, as reflected in the vitriol, intransigence, disrespect, and, dare we say in some quarters, racism heaped on the President of the United States. Surely red and blue have something in common, but some would rather destroy the nation and put our delicate economy in jeopardy than agree with one another. Such behavior reveals a trifling imagination and picayune spiritual life.

Though Lincoln surely knew how to manage and on occasion manipulate and outfox his often -warring cabinet, individually and corporately, he also saw their gifts and brought them out – even when these gifts led them to challenge him – for the well-being of a divided nation. A smaller spirited person would have chosen a team of “yes men” and our nation would have been lost. Lincoln turned “opposition,” a term with violent undertones, into “contrast,” an aesthetic term which focuses on the interplay of diverse pigments, each of which in their diversity is enriched by and enriches the others.

Lincoln’s stature was evident in his response to a questioner in the final days the Civil War. His questioner asked, “What will you do to the South after the War is over?” The questioner, who expected vengeance from the President, was shocked when Lincoln responded, “I will treat them as if they’d never left.”

In the spirit of Lincoln, we need to lay aside the culture and religious wars to take our place as God’s partners in healing the world. We need to reclaim the spirit of Reinhold Niebuhr’s counsel to recognize the falsehood in our truth and the truth in our neighbor’s falsehood. We need to see the holy in all its most distressing disguises, as Mother Teresa notes, and these “distressing disguises” are often the faces of those we describe as our political and theological opposition. I have chosen recently to eliminate the words “opposition” and “opponent “ from my vocabulary, substituting the word “contrast,” because it implies the possibility of complementarity and common ground.

In the height of last year’s battles over issues of budget and the debt ceiling, I was caught up in the polarization that enmeshed most Americans. I realized that my animosity toward certain political leaders was harmful not only to them – in a world of interdependence and quantum entanglement – but also to my own spiritual life. I decided then and there that I would “bless Boehner.” I still held onto my social values and commitment to justice, marriage equality, care for the poor, and earth-keeping. Although my own affirmative theology and politics required me to take a different path than Boehner, Cantor, or the Tea Party movement, I still sought to see the divine within them.

I still seek common ground and look for ways I can work together with religious and political conservatives. I look to Lincoln as a model for my own spiritual and political adventures, affirming the personhood of allies and detractors alike and reaching out to find ways we can become companions in God’s vision of shalom.