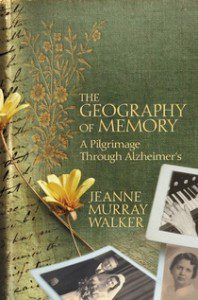

In her new book The Geography of Memory, Jeanne Murray Walker sensitively portrays her experience facing her mother’s Alzheimer’s disease. In the process, she discovers the power of memory to transform her life and discovers a blessing, albeit a difficult one, in responding to her mother’s illness. For this reason alone, not to mention the intimacy and beauty of the writing, The Geography of Memory invites the reader to reflect on her or his own mortality and the mortality of our parents, siblings, and children. Is there a blessing to be found in mortality? Can we find goodness in the midst of life’s necessary limitations, the most striking of which involve the death of mind and body? Is there anything redemptive to be found in illness that ravages the human spirit?

In her new book The Geography of Memory, Jeanne Murray Walker sensitively portrays her experience facing her mother’s Alzheimer’s disease. In the process, she discovers the power of memory to transform her life and discovers a blessing, albeit a difficult one, in responding to her mother’s illness. For this reason alone, not to mention the intimacy and beauty of the writing, The Geography of Memory invites the reader to reflect on her or his own mortality and the mortality of our parents, siblings, and children. Is there a blessing to be found in mortality? Can we find goodness in the midst of life’s necessary limitations, the most striking of which involve the death of mind and body? Is there anything redemptive to be found in illness that ravages the human spirit?

While Walker does not claim to be a theologian, the text is permeated by reflections on God’s presence in situations of loss and limitation. There are no easy answers here nor should theological reflection ever prefer ease over struggle. Simplistic theological answers run aground in times of personal and corporate crisis. Old gods may die and perhaps a new god, more attentive to the pain of life, may emerge.

As I read Walker’s text, two apparently contrasting texts came to mind. Psalm 22’s lament, repeated by Jesus on the Cross, “my God, my God, why have you forsaken me” and Paul’s affirmation from Romans 8, “in all things God works for God.” They appear to express a different theological temperaments, but both emerge from the struggles of faith to affirm God’s providential care amid what Paul describes as the “groaning of creation” in the human and non-human life. These texts may be windows through which to catch the glimpse of a faith worth believing, especially at times when there is no hope for a cure and our loved ones are slowly taken away from us.

I am a pastor who has sought to be faithful to persons with Alzheimer’s and their families. I am also a process theologian, and process theology has shaped my pastoral ministry and response to persons in crisis situations. Affirmative in nature, process theology asserts that God is present in every situation, providing an array of possibilities and the energy to embody these in the concreteness of life. Divine possibility does not limit, but encourages human freedom. God seeks abundant life in every situation. All are chosen to receive God’s grace, but divine grace and power are not irresistible.

Dynamic in nature, process theology also affirms that human freedom and the conditions that characterize our lives may also limit the scope of divine possibility. The parent of process theology, Alfred North Whitehead, notes that God’s aim, or vision for each moment, is the best for the impasse, and that the best may not always in this moment be particularly good. God as well as humankind must face the limitations of concreteness, whether these involve the movement of cancer cells, the loss of memory though Alzheimer’s, unjust and inadequate social conditions, or the impact of heinous and traumatic human actions. All of these can stunt our experience, leaving us scarred for life or render a once vital life decimated.

The affirmative dialogical nature of process theology begs the question: If God is omnipresent, that is, present in all things, and if God aims at wholeness and Shalom, how is God’s vision manifest in such moments of devastation and suffering? Here, I am not primarily addressing the traditional expression of the problem of evil, and its attempt to balance divine goodness and power and the reality of suffering. I am granting from the outset the reality of suffering as something with which God must contend and which is not the result of divine decision-making. I also affirm that although God is ever-resourceful and always present, divine power is always contextual and relational; it is realized in interaction with the free play of the universe, the randomness of cellular life, and the reality of human decision-making. I am also granting that while divine power is universal in scope, from the very beginning – or, as a matter of fact – built in the nature of reality itself, God is always working with a world that has its own integrity in relationship with God. There are some things that God cannot control, and only influence to greater or lesser degree.

The specific questions raised here are: “Does the omnipresent God continue to act in the lives of persons with Alzheimer’s? Does God continue to work in the lives of persons with Alzheimer’s, or does this disease somehow render God’s presence null and void?” Or, in simpler language, “Where is God in Alzheimer’s?”

There are no easy answers, but process theology asserts that God is present within all experience as the “sighs too deep for words.” God is not limited to the conscious mind, but is present in the depths of the unconscious. Could God be providing comfort and calm at the deepest levels of experience? Could God, unbeknownst to us, be moving within the experiences of persons with Alzheimer’s at a place that sustains without curing? If God is not providentially moving within the lives of persons with Alzheimer’s, then omnipresence is a sham doctrine.

God is also present in the lives of caregivers. Being a caregiver for a person with Alzheimer’s or an incurable illness is a day to day burden. Despite our love for significant persons, there is the anxiety of life-threatening illness and the pain of responding to a parent who no longer recognizes you or whose personality has been destroyed by the ravages of illness. There is also the boredom or potential resentment that emerges in day to day care of incurable illness. God is present to nurture our highest selves and to provide comfort, inspiration, and insight, and a second wind when inner resources are at their breaking point. God speaks through us in the nitty gritty realities of persons for whom we care.

Finally, God embraces the experiences of persons with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers. God is the one to whom all hearts are open and all desires known. God’s responsiveness is connected with God’s receptivity. God’s creativity is related to God’s experience of the world. Our suffering and joy matter to God because God feels our lives from the inside, not as an observer, but with the same intimacy as parents, siblings, and children experience their significant others. God feels the sense of defeat and hopelessness as well as moments of memory and mirth. God’s victories are not unilateral, but reveal the tragic beauty that characterizes real life at its best.

There may be, as Jeanne Murray Walker discovers, a deep grace to be found in caring for vulnerable loved ones. There are no victories but the possibility of healing and reconciliation even when there cannot be a cure.