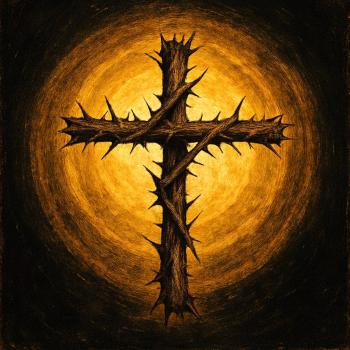

What do you do with Good Friday and the Cross when you’ve abandoned the centrality of the doctrines of substitutionary atonement and the divine necessity of Jesus’ death? Like many progressive Christians, I grew up hearing the mantras “Jesus died for our sins,” “Jesus died so that we might have eternal life and escape God’s wrath,” “Jesus paid the price for our salvation,” and “sin deserves death and Jesus stood in our place.” Recently, I saw a billboard with the stable and manger and three crosses in the background, with the description “born to die.”

Although I no longer believe in substitutionary atonement, I must confess that I still sing the songs of my childhood faith with their emphasis on transactional and vicarious atonement, “The Old Rugged Cross” and “How Great Thou Art.” Though I no longer believe the words of “How Great Thou Art” –

And when I think, that God, His Son not sparing;

Sent Him to die, I scarce can take it in;

That on the Cross, my burden gladly bearing,

He bled and died to take away my sin

Then sings my soul, my savior God to thee,

How great thou art

How great thou art. –

the hymn is still dear to my heart and represents the simple faith of my small town Baptist childhood.

Without reflecting on the meaning of their favorite hymns or the impact of Jesus’ death in the drama of salvation, many 21st century Christians, who regularly use AI, ponder photos from the Hubble telescope, marvel at images of black holes, go to Sikh and Hindu doctors, and believe that humankind emerged from a multi-billion year process of evolution, assume the following statements reflect the essence of Christianity:

• Human sin brought death into the world.

• We are born steeped in this original sin.

• Human sin deserves divine punishment.

• Jesus came to break our bondage to sin.

• Jesus’ death was foreordained and Jesus lived his adult life knowing he was going to die on the Cross.

• Jesus’ death is God’s way of securing our salvation.

• Only a divine sacrifice can free us from sin and insure eternal life, rather than eternal damnation.

• The only pathway to salvation is a personal relationship with Jesus, demonstrated by an explicit affirmation of our sin and the sole salvation of Jesus Christ.

Many believe that these are the only possible Christian understandings of the cross, forgiveness of sin, and salvation, and have left Christianity because these beliefs no longer reflect their personal experience or offend their ethical and spiritual sensibilities. They yearn for alternative ways of viewing the cross and the nature of divine sacrifice. They are looking for good news beyond God’s sacrifice of his son for salvation.

Although these “orthodoxies” of the past – claimed to be the only to understand the cross by some – may have provided assurance for us once upon a time, to many of us who still call ourselves Christian, they no longer make sense, nor do we believe in a God who requires the death of “his” son to secure our salvation. We also see divine grace operating in other religious traditions and in the experience of faithful agnostics. Still, many of us attend Good Friday services; some of us even preach at such services, despite our theological and liturgical reservations. Our quest to be faithful as we remember Good Friday begs the question: Can we as progressives “redeem” Good Friday in a way that affirms the interplay of divine love, human creativity, and human brokenness, while avoiding dubious theologies that assume salvation requires violence, including the predestined death of God’s only Child

We do not need to celebrate divine violence on Good Friday or any occasion, but we live in a world characterized by implicit and explicit violence against the Earth, child and adult slavery and sex trafficking, political gridlock, disparity between the wealthy and vulnerable, racism and injustice, the death of children in Israel and Gaza, and political unrest in our own democracy. Not to mention the violence involved in climate change and election denial, often perpetrated by those who claim to be the most “orthodox” Christians. When we open the doors of perception, we are only too aware that our precarious planetary situation and the threat to democracy is a result of human decision-making and the machinations of powers and principalities. We recognize that we need a loving power greater than ourselves to save us, and we also know that our salvation and the future of the earth depend on our willingness to be actors, rather than passive observers in the healing of the earth. We need theologies that recognize that Jesus’ saving action inspires our own willingness to become partners with God in saving the earth.

I believe that we can creatively remember Good Friday in worship and ritual by reflecting on the interplay of our personal and institutional shortcomings and God’s passionate companionship. “Were You There When They Crucified by Lord?” is the quintessential Good Friday hymn. Of course, none of us were there physically. But we are all part of an ambiguous history that persecutes prophets and promotes celebrities. On Good Friday, we can ponder all the little crucifixions going on right now in our world, often unnoticed, but very real – death dealing actions that lead to melting polar icecaps, global climate change and the potential cataclysm that awaits our children and children’s children, complacency at mass starvation and genocide, apathy at sex trafficking and human slavery, our addiction to oil and gun ownership, and the list goes on, even before we explore our own personal ambiguities and culpability in the subtle violence of everyday life.

Even though Jesus’ death was neither foreordained nor necessary to appease God’s wrath, we can recognize that we are no better morally and spiritually than many of those who shouted for Jesus’ crucifixion, stood idly by doing nothing to prevent it, and implicitly sentenced Jesus by their involvement in political and religious institutions. Are our political leaders – and we as USA citizens – any more moral than Pilate or the Jewish religious leaders? We also operate out of self-interest and are willing for many to suffer or die for the “American way of life.”

Good Friday also affirms the tragic beauty of God’s relationship with the world. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, from the vantage point of a prison cell, proclaims that only a suffering God can save and Alfred North Whitehead speaks of God as the fellow sufferer who understands. Throughout the centuries, Christians have debated the doctrine of patripassianism, the belief that God the Father suffers on the Cross with the Son, Jesus. While patripassianism, or divine suffering, has been labeled a heresy those who presume themselves to be the upholders of orthodoxy, based on the belief that the divine nature is incapable of suffering and that Jesus’ suffering touched his humanity but left his divinity unsullied, I believe that the deeper “heresy” (and heresy is a term I seldom invoke) is the belief that God does not suffer with the world. A changeless, unfeeling, and apathetic God can neither heal nor save. In contrast to a passionless deity, a meaningful vision of Good Friday proclaims that God suffered – the whole of God suffered – on the cross and in every moment creaturely suffering. God is not apathetic to our pain, God is empathetic, feeling our pain.

Difficult as it is to admit our complacency and culpability, we can on Good Friday answer “yes” to the question, “Were You There When They Crucified My Lord?” We can also say “yes” to the grace that feels our pain and regret, the pain of those broken by the world’s greed and complacency and live in the hope that the One who feels also forgives and transforms and enables us to rise up with new energies for global healing. Then the cross becomes the pathway to responsible partnership with God in seeking healing and justice for our good earth and its human and non-human creation.

+++

Rev. Bruce Epperly Ph.D. has served as a professor, seminary administrator, university chaplain, and congregational pastor at Georgetown University, Wesley Theological Seminary, Lancaster Theological Seminary, and South Congregational Church United Church of Christ on Cape Cod. “Retired,” he continues to teach in the Doctoral of Ministry program at Wesley Theological Seminary, give seminars, write, and rejoice in grandparenting and marriage with Rev. Dr. Kate Epperly. An ordained minister in the United Church of Christ and Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), he is the author of over eighty books, “The Elephant is Running: Process and Open and Relational Theology and Religious Pluralism,” “Jesus: Mystic, Healer, and Prophet,” “Walking with Francis of Assisi: From Privilege to Activism,” “Simplicity, Spirituality, and Service: The Eternal Wisdom of Francis, Clare, and Bonaventure,” and “Taking a Walk with Whitehead: Meditations with Process-Relational Theology.” His books on faith and politics include, “Talking Politics with Jesus: A Process Perspective on the Sermon on the Mount,” “One World: The Lord’s Prayer from a Process Perspective,” and “Process Theology and Politics. His most recent texts are a trilogy: “Process Theology and Healing,” “Process Theology and Mysticism,” and “Process Theology and Prophetic Faith.” He may be reached at [email protected].