The story of Noah and the Flood is a literary genre that we might call “scary story.” Hebrews adapted it from the Babylonian culture, where it was much scarier. The Bible’s story helps us imagine that our whole world is as precious as if it had been saved from a flood.

Episode 5 of the Rowing with Michael Series: A journey through the Jewish/Christian Scriptures in Verse and Commentary. Introduction and Contents for this series HERE.

Michael, row the boat ashore. Alleluia….

- God told Noah, “Build an ark,” Alleluia.

- “Before this world is a water park.” Alleluia.

- So Noah built a great big boat, Alleluia.

And set a new history of the world afloat. Alleluia.

The Flood, a story … or stories

I was at an adult faith enrichment class and casually mentioned that the Flood didn’t actually happen. It came as a shock to many of the participants. Happily, though, the presenter backed me up. The Flood story in the Bible is just that, a story. The biblical author based it loosely on one of the oldest stories that have survived from the ancient world, the “Epic of Gilgamesh.” It comes from the Babylonian culture just about straight east from Palestine.

There’s more than one biblical author for this story. You can tell that if you consider how many of each kind of animal Noah took on the ark. God tells Noah to bring with him a pair of each animal species. Then God turns around and says to bring seven pairs of each clean animal and one pair of each unclean animal. Finally the story turns again and shows Noah taking only one pair of each animal onto the ark.

Reading the Bible can be confusing, but scholars have sorted this one out. The Hebrews told two different flood stories. In one of them the storyteller wanted to have Noah offer a thanksgiving sacrifice to God and didn’t want him to cause the extinction of a species he had just saved. So he had his hero take some extras of the clean animals, the ones acceptable for sacrificing. The other author didn’t want Noah sacrificing anything because he wasn’t technically a priest. This latter story only needed two of each species. A final editor wove the stories together and included everything, even the contradictory details. I guess that shows how much ancient cultures valued literary traditions.

Neither the original storytellers nor the final editor felt any compunction about changing an older literary work. In the Babylonian story one god was annoyed with the humans so he decided to wipe them out in a great flood. Another god got wind of the plan, tipped off one of the humans, and really ticked off the first god. It just wasn’t what the Hebrew people were beginning to understand about divinity, namely that God acts justly.

Still the picture of a god who would destroy a whole world, including children and animals, even for a good reason seems a bit too vindictive. It’s helpful to know that the violent part of the story was around before the Israelites got to it. I think the important thing–the divine message, or the revelation–in the Bible’s version is not in the original Pagan story but in how God’s people changed it.

A precious world

There’s a special feeling that you get from stories, like the Flood, about near total destruction. We see it also in survival stories like Robinson Crusoe and the popular Armageddon-like movies. It’s a feeling of the precariousness of all existence. The first thing Crusoe does after his shipwreck is make a list of everything that’s left. Because it’s so little, it’s all precious. The same feeling of precariousness and the preciousness of all that’s left is part of the message of the story of Noah’s ark.

The Israelites had a scientific reason for this feeling. Here’s a bit of early Israelite science:

The Israelites had a scientific reason for this feeling. Here’s a bit of early Israelite science:

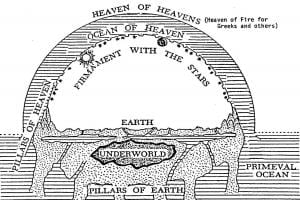

- God created the world in the middle of raging waters above, below, and on all sides. The world looks like an air bubble with a flat bottom in the midst of the waters. After first making day and separating it from night, God made the firmament, or sky, (the top of the bubble) that separated the waters above from the waters below. Then he gathered the waters below into certain places so dry land appeared.

- There are gates in the sky above that open downward. Usually God keeps them closed. It rains when God lets them drop open a tiny bit.

- I don’t know if all Israelites actually believed the story of the flood, but they did believe there was enough water around to make it happen. And it would happen, too, if God wasn’t on the ball with those gates. God was saving them from the flood all the time.

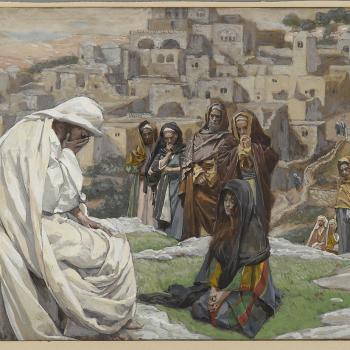

Being saved from a flood or shipwreck has a way of enhancing the value of each little or big thing saved along with you. I imagine Noah getting off the boat and looking around. Everything he sees has been saved from a tremendous wreck. Any single item, or for that matter the whole works, might have simply disappeared. He would make up his mind to do everything he could not to lose a single item on his “list” because each one has been saved for a reason. Each one is irreplaceable. (Too bad he went and, in a forgetful moment, ate one of the pair of unicorns!)

We have no scientific evidence that there ever was a universal flood, but we do have scientific evidence that the existence of life in this universe is precarious like that bubble of a world in the Bible. We would do well to hold everything around us as dear as if it has been saved from a flood.

Clean and unclean

Why would God designate some animals clean and others unclean? In the beginning, as the story goes, there was no meat eating at all. God gave Adam and Eve and all the animals “all the green plants for food.” This is not meant to be either scientific or historical but to say in symbol how peaceful God’s creation was meant to be. After the Flood it’s as if God decides to be more realistic. He approves using animals for food, but still not all of them. Humans are only allowed to eat meat from “clean” animals.

I don’t think there was ever a time when some spokesperson for God said, “Alright, folks, God says we have to quit eating pork chops.” A dietary custom was later put into a story. Other societies had food laws, too, some of them much stricter than the Israelites’. Some people say these customs developed for reasons of health, but I doubt it. God, in the Bible stories, never says that there is anything wrong with “unclean” flesh or the Forbidden Fruit, either. “Just don’t eat it!”

Dietary taboos often show respect. Hindus and other vegetarian societies showed respect for the souls of ancestors, who were believed to inhabit various animals. The Israelite custom shows respect, too—not respect for a human soul living in an animal but for the animal itself and the whole created world. The Israelites didn’t despise the animals that they wouldn’t eat. After all, God created them too, and their storied ancestor Noah saves them. They used the goods that nature afforded them, but they limited this use.

Israelites could not believe that the whole universe was there just for them. They believed nature had a more exalted reason for being—to worship God. Their own worship was just a part of this cosmic service. As God’s appointed “rulers” of creation, they added another dimension to this worship, making it conscious and free. But the worship was there before and outside them; they didn’t own it any more than they owned nature.

Consumers and producers

We no longer see ourselves as part of a cosmic service in praise of the creator. Nature is no longer the powerful context of our lives as it was for ancient societies. Commerce takes nature’s place. We allow ourselves to be identified as consumers and producers. The other day a radio commentator was talking about poetry and “consumers” of poetry. It sounded like blasphemy to me, but it’s the story we tell about ourselves.

Nature itself is a product that we consume, partly by visiting managed “natural” places and appreciating their beauty, but mostly by destroying things, using nature up. The environmental crisis, including climate change and rising oceans, is the consequence of our overuse and misuse of nature. And that takes us back to the story of the Flood and the rainbow promise:

- God said the seas won’t rise again.

- Unless it’s the work of women and men.