Is  Abraham an imaginary figure or a historical person? If historical, what does a Catholic make of the fantastic stories the Bible tells about him. What can the rest of the world make of the god of Abraham?

Abraham an imaginary figure or a historical person? If historical, what does a Catholic make of the fantastic stories the Bible tells about him. What can the rest of the world make of the god of Abraham?

Episode 7 of the Rowing with Michael Series: A journey through the Jewish/Christian Scriptures in Verse and Commentary. Introduction and Contents for this series HERE.

Michael, row the boat ashore. Alleluia….

- Abraham was as good as dead. Alleluia.

- Still he believed what the Lord had said. Alleluia.

- Sarah laughed when she heard the news. Alleluia.

- “We’re gonna need diapers and baby shoes.” Alleluia.

Catholic Bible scholars are fairly unanimous in characterizing the stories in the first 11 chapters of Genesis—Creation, the Fall of Adam and Eve, the Flood, the Tower of Babel. There may be mythical elements in some of them, but they are not just myths. They are, however, stories, made up by anonymous story-tellers or anonymous writers. Some may have originated in Israel, earlier or later in that nation’s history, some may have started in other cultures and been borrowed and adapted by Israelites. The long and the short of it is that they are fiction.

The same unanimity among scholars does not persist through the rest of Genesis. There is a great deal of uncertainty about how to describe the stories of the patriarchs, starting with Abraham. Was Abraham a real person? What about the other patriarchs? The Catechism of the Catholic Church acknowledges the uncertainty in these words:

Given the lack of decisive evidence, it is reasonable to accept the Bible’s own chronology [and] that the patriarchs were the ancestors of Israel. (U.S. Catholic bishops on Genesis)

In other words, the traditional view is “reasonable.” It is not demanded of Catholics who want to investigate further. In fact, the traditional view is not accepted by all Catholic scholars. I won’t be taking a position on this issue, but a related decision seems necessary. I think one must take many of the stories of the patriarchs, as opposed to their existence, as legendary tales with no or scant basis in historical fact.

Was Abraham really 100 years old when he and Sarah had their first child? Did Abraham really hear God telling him to offer Isaac in sacrifice? Did Abraham really almost successfully argue God out of destroying Sodom? Doubts about all these and more are well within the bounds of Catholic teaching about the Bible.

The Bible is a human as well as a divine product. The ways of humans are not always easy to figure out, but we know memory is imperfect, stories get exaggerated, details get added, and whole made-up stories can, after a time, come to seem real. It has happened in our country’s history—witness the made-up story of George Washington and the cherry tree (a morality tale that in my youth I learned as history) or the ride of Paul Revere (history that morphed into an inspirational lesson). There’s every reason to suspect that the same transformation of stories into seeming history happened also in the formation of the Bible.

What exactly is revelation?

Jews and Christians believe that God acted in history. Their religion is not just ideas about God and some moral expectations but a story in which God is the main character. The connection between the story and actual history is always an important question, so scholars undertake the difficult work of uncovering history from the traditions.

Believers can always bypass this difficulty by saying that God gave either the storytellers or the writers some supernatural help so we end up with a product that is “inerrant” (as the technical word goes) and actually beyond human ability to produce. That’s a common enough view of what revelation is, but I think most Protestant and Catholic scholars, except fundamentalists, reject it. The Catholic Church says God works within, not outside of or against, people’s human, God-given abilities.

How does a Catholic find history in the pages of the Bible? Since there is both story and history in the Bible, it’s one of the businesses of scholars to tell the two apart. Most scholars agree that this can be done, though imperfectly and with varying degrees of probability. We can detect a historical core in many of the stories. Even with the uncertainty in telling story and history apart, we can say that both are interpretations of real events in the light of the faith of indisputably real people.

That last point means there is history throughout even in the storytelling, but it also means that we never, even in the most historical writings, get history straight. It’s always history interpreted, history colored by the demands of faith. It’s exactly the way people all over, until fairly recently, have written and told their histories, whether sacred or not. I like to say God is OK with that.

Historical fiction

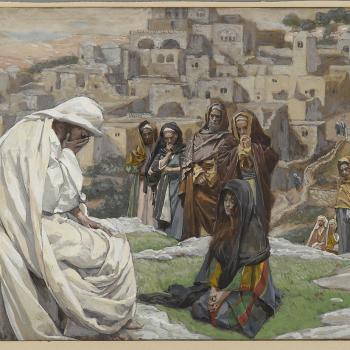

So the Israelites’ story of salvation begins with Abraham, a kind of historical fiction, if you will. And it’s historical fiction whether or not Abraham was real. As a religious story, it’s still quite distinctive. It’s not a myth, taking place in some aboriginal or dream time. It is set very deliberately in human history, around 8 or 9 hundred years before King David (a verifiable historical figure). Here time, place, and particular individuals and groups are important.

Abraham is not just another symbol standing for humanity in general, like those we find in the first 11 chapters of Genesis. The story of Abraham leads through definite times and places to the history of the Israelite/Jewish people and the Christians and Muslims too. The rest of the world does come into the story. God says that by Abraham and his descendants “all the families of the earth will bless themselves.” When parents bless their children they’ll say, “May you be like Abraham and Sarah, Ruth, David,” etc.

People ask: Why should the rest of the world bless themselves in the name of these people or even Jesus? There are other worthy heroes. Why not “May you be like Socrates, Buddha, or Confucius”? The Bible says God’s involvement in human history is particular. It starts in one time and place and reaches out from there to include everyone everywhere. Is it fair that God should lavish special attention on one small group of people?

Intellectually it’s weird. You can’t reason to such a God from general principles or universal human experience. But I find it very much like human love. There’s no such thing as love of everybody in general. It has to be particular and reach out from there. I can warm up to a god who becomes available in history slowly and haltingly, depending on often-erring men and women. A god anyone could reach independently of time and place—the way a scientific law has to apply “fairly” throughout space and time—would be intellectually satisfying and interesting, I suppose. The god of Deism is interesting, but I wouldn’t love such a God. And, anyway, it wouldn’t make a very good story.