I’ve been searching through the Old Testament for stories Jesus might have told the disciples on the way to Emmaus. Jesus, without their knowing who he was, explains why the Messiah had to suffer in this story from Luke’s Gospel. My guide in this search is René Girard. His theory about rivalry, the scapegoat, and religious violence helps me select and interpret certain Bible stories. Here I take a look at Girard and a theory about the scapegoat that explains what lies behind much of human history.

Episode 2 in the series “Opening the Scriptures on the Way to Emmaus: Why Did Jesus Have to Suffer.” Introduction and a Table of Contents here.

In the last post’s story a “human sacrifice” was able to restore a dysfunctional community to a cooperating unit. The Israelites had known a big defeat; they blamed Achan; they killed him. This victim’s death renewed the harmony that enabled the ensuing victories. All of this was orchestrated, according to the story, by the unseen force they called God. In their minds it was God whom they offended, God who punished, and God who rewarded when satisfaction was complete. But really it was a mechanism that we see all the time in human relations. It’s called the scapegoat.

The scapegoat in the Bible and history

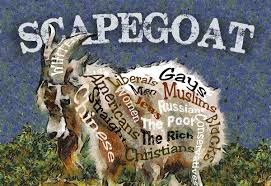

The Israelites had a ceremony in which the people would symbolically lay all the sins of the community on a goat and then send the sin-laden creature out into the wilderness to starve or be eaten by wild animals. (Leviticus 16:20-22)

This scapegoat mechanism has played an important role in human history. It singles out and shuns someone or some group who are not “WE.” It strengthens the sense of “US.” We become a more cohesive group, and we can forget whatever may have been dividing us and go out and do “great” things.

Here’s the catch. For one who understands the mechanism the way I just explained, it won’t work. The truth has to be hiding, the mechanism unconscious. In human history purity and taboo, sacrifice and myth are the tools, the lies, that have accomplished that. Another word for it is “religion.” René Girard discovered the scapegoat mechanism, hidden or more or less exposed, at work in literature and religion.

Girard imagines a much older history: Religion’s Beginning

You might guess where Girard takes his theory – toward an explanation of the origin of religion that doesn’t require any real gods. It just needs a few reasonable assumptions about human nature and a plausible story.

Humans, by nature, are especially good at imitating each other. In particular we imitate each other’s desires. What we think of as our own desires are really, Girard thinks, imitations of the desires of another. Advertising illustrates this dynamic: a sports hero praises some shoes, and we go out and buy that brand. A child contentedly playing with one toy sees another child with a different toy, and suddenly wants that one. Adults always want to “keep up with the Joneses.” Scientists have even discovered a gene they called “mimetic” – related to imitation. Such rivalry often leads to conflict.

As a species we very early lost the instinctive restraint that, in other imitative animals, ends a conflict before it becomes a fight to the death. These other animals establish hierarchies rather easily, but we have no instinct for accepting our place, especially if it’s a lower one. Something must have restored that restraint or we would long ago have disappeared as a species. How that may have happened constitutes Girard’s plausible story.

Girard hypothesizes a story about human beginnings

A band of proto-humans was on the verge of self-destruction. Possibly some toy or tool had become the object of every creature’s desire. Everyone was everyone else’s rival in the struggle to possess that object. Chaos threatened. But the human tendency to imitate each other’s desires turned from rivalry to cooperation in a process very familiar to all of us—“ganging up on someone.” Usually it would be someone who is different from the others in some way. We project onto that other the blame for our troubles.

Suddenly in that ancient gang there’s this new thing to imitate: “Get Shorty!” Poor Shorty doesn’t stand a chance. Everyone else feels great to belong to such a wonderfully cooperative group again. As often happens, in the rush of solidarity they’ve forgotten what the original fight was about.

Nobody knows how that new unity among the gang came about. It’s like a miracle. But everybody knows who belongs and who doesn’t because they have the wrong look about them or violated some spoken or unspoken rule. Nazi Germany is a perfect example of this “miracle” of solidarity that arises from blaming a scapegoat.

Religion begins

Girard thinks that this dynamic—which no one understood or it wouldn’t have worked—tended to be sacrilized. Taboo and ritual, purity codes and sacrifices, especially human sacrifices, arose as a more stable form of this same mechanism. Eventually a story, or myth, makes sense of all these while hiding the real truth. In a word, we have religion.

With a religion you don’t have to wait for a crisis before calling forth the mechanism, the “sacred violence,” that strengthens the group’s identity and unity. You can have regularly scheduled sacrifices, priests, maybe kings. A whole bureaucracy and a system of laws, lawyers, judges, and politicians follows. We get hierarchy and layers of prestige and authority after all. This time it’s by custom instead of, as in other animals, by instinct. The human race, minus a few sacrificial victims, survives.

Girard thinks that human culture and the hierarchies that instruct everyone on where they belong arose this way. Human history started with this deceitful and cruel mechanism of sacred violence. So, in terms of one Christian myth, religion is about the same as Original Sin. Salvation, as Girard sees the Christian concept, would start with the unmasking of the mechanism of sacred violence.

Girard surprises everybody

I expect that religion could have a natural explanation. I like this theory better than some others by atheist scientists (religion as faulty science) or psychologists (religion as a coping mechanism). Admittedly, it connects religion with some of the worst things humans do to each other, but religion obviously has such connections. Girard’s theory places humans within the natural world. From there we step out into an artificial space, where the uniquely human begins.

I imagine quite a few of Girard’s atheist readers were pleased to have a new theory to “explain away” religion. Reading his later work, they found out he was not doing that at all. Quite the opposite, in fact. Girard is a Catholic, a convert. Actually he returned to the Catholicism of his youth. A number of theologians have praised Girard’s work.

The way Girard manage to combine Christian faith and theorizing about the origin of religion is by looking closely at the Bible. It’s a place where episodes of sacred violence (fictional or historical) are recounted. More important, it’s a place that exposes and criticizes the mechanism of sacred violence. This critique gradually develops in the Hebrew Scriptures and comes to particular clarity in the story of Jesus.

In the next posts I’m going to look at more stories from the Hebrew Scriptures that unmask the scapegoat mechanism. In the process they have something to say about Jesus and the meaning of his death.