A story of a sacrifice that shouldn’t have happened seems an unlikely candidate for Jesus to use to explain his own death. But the story of Jephthah and his daughter makes us focus intently on the sacrificial victim. In this case the victim is the real winner, at least long-term in Israel’s memory. So I’m proposing this as another of the Scriptures that Jesus opens up for the disciples on the way to Emmaus.

Episode 6 in Opening the Scriptures on the Way to Emmaus: Why Messiah had to Suffer. Introduction and links to other posts in the series here.

The victim’s point of view

The ability to see the point of view of the victim is part of the genius of Hebrew Scripture, but it’s sometimes there and sometimes not. God punishes Cain for the murder of Abel, but God also sympathizes with Cain, giving him a mark so that no one will dare kill him. God doesn’t want a second victim after Abel’s death.

In another story God saves a victim people—the Hebrew slaves in Egypt—and in the process creates another large group of victims. Egyptians suffer and die; and not all of the ones who suffered were guilty. The account in Exodus shows not the slightest sympathy for them. There’ is, however, this custom in the Jewish Seder celebration:

During the course of the Passover meal, wine is ritually spilled in compassion for, and solidarity with, the suffering caused to the Egyptians by God’s deliverance of Israel at the exodus. (This is a quote from J. Richard Middleton and Brian J. Walsh, Truth is Stranger Than it Used to Be, p. 93.)

The sacrificial victim remembered

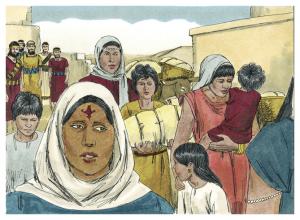

Jephthah’s story forces us to see a victim’s point of view. The victim is Jephthah’s daughter. Here’s the story more or less as the Book of Judges presents it:

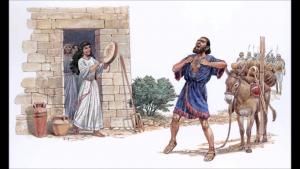

Jephthah, a judge of Israel, is worried about an upcoming military campaign. As insurance, he promises God that, if he wins the battle, he will sacrifice the first individual who comes out the door of his house to greet him on his return.

He wins the battle, and the first person out the door to greet him (you could guess this) is no slave but his beloved daughter. There’s no divine intervention to save the sacrificial victim this time, and the unnamed daughter says,

“Father, you have made a vow to the Lord. Do with me as you have vowed, because the Lord has wrought vengeance for you on your enemies the Ammonites.”

She does request, and is granted, two months reprieve to go off and “mourn her virginity” with her girlfriends—no boyfriends allowed. (Judges 11:29-40)

We can see the rashness of Jephthah’s vow, and there’s that moment of sympathy for the daughter at the end. This way the story makes it clear again that God does not approve of human sacrifice. But the victim is the lasting interest of the story:

It then became a custom in Israel for Israelite women to go yearly to mourn the daughter of Jephthah the Gileadite for four days of the year.

Undermining the common idea about sacrifice

There’s something especially touching about the daughter’s acceptance of her role as sacrificial victim. The connection with Jesus is impossible to miss.

The strangest part is God’s honoring Jephthah’s vow. If I had written this story, I would have cut it off half-way through. Jephthah would have lost the battle for making such a stupid vow. My story would have spoken against human sacrifice, but the Bible’s story helps to undermine a whole false ideology of sacrifice.

Jephthah gets what he asked for even though his promised sacrifice is completely inappropriate. And was the ensuing murder of the child a sacrifice made to God? Not at all! It was a sacrifice to Jephthah—not to secure his victory because that was already won, but to safeguard his honor. He could have broken his vow, but he would have had to admit he was wrong and stupid to have made it. He might have lost some status as Israel’s leader.

If this story is one that Jesus would have used to tell about himself, then Jesus is Jephthah’s daughter. A tender ego and delicate power relationships needed her as their sacrificial victim. We can imagine the powers that controlled the world of first-century Judea needing Jesus’ death to keep going.

Now the important question is: Can we imagine Jesus willingly going along with that system and somehow defeating the system in the process? Maybe so, since Jephthah’s daughter without a name triumphs over her father in the long run, in Israel’s memory.

Image credit: Carelink Ministries via Google Images