St. Paul wrote: “The weakness of God is stronger than human strength.” (1 Cor 1:25) Formerly, I translated this in my mind as a clever way of saying, “God’s strength is really strong.” I take God’s weakness more literally now.

This is the third in a series on the Creed of Christians. An introduction consists of my retelling of the Creed’s story. That and links to other posts in the series are here.

God’s kingdom

When I look at Jesus, I don’t see a lot of his own power, even when it comes to the miracles. Jesus would always credit a miracle to something else. It’s a person’s faith. “Daughter, your faith has saved you.” (Mark 5:34) It’s the new thing that’s happening all around. “Cure the sick and say to them, ‘The kingdom of God is at hand for you.’” (Luke 10: 9)

When I think of kingdoms and kings or other human rulers, I think of power. Looking at Jesus, that doesn’t seem to be his way to think of God’s Kingdom. God rules, but what is God’s manner of ruling?

“You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and the great ones make their authority over them felt. But it shall not be so among you. Rather, whoever wishes to be great among you shall be your servant; whoever wishes to be first among you shall be your slave. (Matthew 20:26-27)

God rules, but not by wielding power over subject people. There’s practical wisdom in that.

The things power can’t do but weakness can

A young Jew had been riding toward Damascus on a mission. Saul had all sorts of power. He had strength of character, vitality, backing of the authorities, an armed band accompanying him. Saul was used to the ways of power. He obviously had been expecting resistance from Christians, the ones he intended to “persecute.” That’s the word a voice in his head had used.

He had not been expecting that voice and wasn’t prepared for what it said. It didn’t seem to come from his familiar world of power. It posed no threat that he could tell. Just a simple question and a bit of telling it like it is: “I am Jesus. You are persecuting me. Why?” (Acts 9)

Here’s the truth about power: No amount of it would have converted this man, who became Paul, the Apostle to the Gentiles. What if Saul had met hostility, resistance, or self-righteousness among Christians equal to his own previous bluster. Whatever stirrings of doubt he might have harbored would have been buried under an avalanche of self-defense.

No amount of divine power can accomplish the things that God wants most. But power invades much of our thinking about God, whether it’s “my Higher Power” or the “power” of love. My guess is that God isn’t very interested in power.

The power (?) to create

Jesus didn’t show any interest in his own power, but in the beginning God created the world—out of nothing. I was taught once that there is an infinite distance between nothing and something. Mustn’t it have taken infinite power to bridge that distance and create the world?

I look at the story of creation in Genesis, Chapter One. In comparison to creation epics of Israel’s neighbors, Israel’s God had an easy time of it. God didn’t have to slay any monsters like Tiamat, whose split carcass became earth and sky in one epic. God spoke into the nothingness, and the heavens and the earth were. Yes, there’s an infinite distance between nothing and something, but my experience of working on old houses tells me: Starting from scratch is easier.

There’s a myth in Plato’s Timaeus in which a being Plato calls the Demiurge doesn’t start from scratch. This Demiurge makes a world out of pre-existing matter consisting of geometrical shapes. The “urge” in Demiurge comes from the Greek word for work. It’s real work putting form into that recalcitrant matter. The ideal forms in the Demiurge’s toolbox don’t quite fit those geometrical pieces so the world in Plato’s myth tends to fall apart. In Genesis God starts with the closest thing to “scratch” the Israelite mind could conceive. The the author calls it chaos. God, the creator of heaven and earth, has none of the Demiurge’s problems.

The Hebrew Scriptures and God’s power

God’s power is a major theme in the Old Testament. God’s mighty arm punishes Pharaoh and rescues the Hebrews from slavery. God is a warrior who wins battles for Moses and Joshua. Those were huge displays of power, but a story about Aaron in the Book of Exodus has impressed me even more.

Aaron is Moses’ right-hand man during the wandering in the desert. He’s also high priest with the duty to enter God’s presence in the tabernacle. He has to take special precautions when he does. He must wear a robe with bells tied all around the bottom hem. Otherwise he will die. (Ex 28:33-35)

God radiates so much power that it would kill any mere human who comes too near. But the bells give warning that somebody is coming, and God gentles his power a few notches.

Still, amidst all this divine power, there’s some ambivalence about power in the Old Testament. There’s a dramatic scene in the story of Elijah. (1 Kings 19:1-13)

Elijah was exercising some of God’s power. He put to the sword all of King Ahab queen’s favorite prophets, prophets of Baal. Now he’s in trouble from the queen. He flees for his life to the mountain of God, Horeb. There the Lord tells Elijah to watch because “the Lord will be passing by.”

Elijah expects a great display of God’s power, and he does, in fact, witness rock-crushing winds, an earthquake and fire. But the Lord was not in any of those things. Then comes a “tiny, whispering sound.” God famously speaks to Job out of a whirlwind, but to Elijah it’s just a murmur. Eventually Elijah gets the help he needed, but not from God directly. God has him anoint a couple kings of Israel and Judah and get himself a successor prophet named Elisha. They will save Elijah’s life and destroy the idolators.

Weakness and power in the New Testament

In the New Testament Jesus becomes God’s instrument, but not primarily by performing powerful deeds. Miracles are part of Jesus’ story, but what defines him is humble obedience. Obedience leads to Jesus’ death on a cross—a result that God surely did not want—but God didn’t intervene to stop it, either. Whatever God’s will was, no amount of power was going to accomplish it.

It’s hard to find a mightier display of power than at the end of the New Testament, the Book of Revelation. The seer, who calls himself John, has a vision of a scroll with seven seals. (Revelation, Chapter 6)

As the seals are broken one by one, all sorts of powers are released. A white horse and rider with a bow gallops forth. A red horse and a rider with a sword take peace away from the earth. A black horse brings what looks like price inflation in the barley and wheat futures. Not that it matters much because the future isn’t going to last very long. A Green horse with a rider named Death brings sword, famine, and plague to a quarter of the earth.

The breaking of the fifth seal wakes up the souls of those “slaughtered because of the witness they bore to the word of God.” They wait for the next-to-the-last seal which will avenge their blood. With that sixth seal the sun will turn black and the moon blood-read, stars will fall, and mountains will move from their places.

That’s only the beginning of the troubles. It makes exciting, gruesome reading in symbols that are hard to figure out. But one thing is clear right away. All this power is only secondary. None of it comes to pass unless somebody opens that scroll with the seven seals. That would have to be somebody immensely powerful, right? Wrong! Here’s how the episode with the seals starts:

John, the seer of these visions, is weeping because no one seems to be worthy to open the scroll. An elder says not to worry; the Lion of Judah is coming. He has triumphed, so he can open the scroll. But what does appear is the opposite of a lion in strength. It’s a lamb. Not only that, but the lamb seems to have been slain.

The lamb, of course, is Jesus. The Book of revelation is about one who triumphed over the “powers,” but not by strength. God’s weakness is greater than strength.

The dynamics of weakness and power

I think we have to continue speaking of God’s power, and we have to keep on singing “A Mighty Fortress is Our God.” But, applied to God, power is only a human metaphor, and it can mislead as well as lead. We need the contrary metaphor of weakness. In the dynamics of these two metaphors—this is the world-shaking Christian insight—weakness is primary.

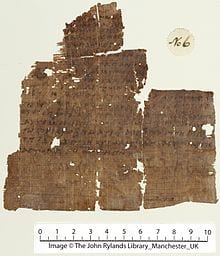

Image credit: Wikipedia