Inclusive language is an important, but puzzling, theme in the Church’s life.

I was at a dinner party with friends, and after we’d drunk a decent amount of wine, the conversation turned to religion. I made a statement referring to God as “he,” and one of the participants immediately corrected. “You mean ‘she,’ don’t you?” I thought, If I’m going to talk about God when I’m this far under the influence, I shouldn’t have to worry about inclusive language or my personal pronouns.

This is the sixth in a series on the Creed of Christians. An introduction consists of my retelling of the Creed’s story. That and links to other posts in the series are here.

I think the movement toward inclusiveness—less masculine language, more feminine images—in the way we speak about God is a good thing. I’m just not sure how far inclusive language should go. We need to give this controversial issue time to sort itself out.

Some beginning thoughts about inclusive language

- It’s good to have more than just masculine images for God. To king, judge, father, we could add friend, lover, counselor, consoler, advocate, solid rock, companion, patron, support, friend, source and ground of our being—and mother.

- The English language is unusually big on personal pronouns. We use the words “he,” “him,” and “his” much more often than, say, Spanish or Latin. In both the latter languages “he” is often omitted. The Spanish “his” doesn’t even look or sound masculine, and in Latin it takes the gender of the word for thing possessed, not the possessor. The result is that language about God sounds a whole lot more masculine in English than it does in some other languages. If inclusive language is important anywhere in the world, it’s in English-speaking countries.

- Some religious speakers and writers, sensitive to the impressions that even the sound of language can make, have found ways to say what they want to say without using quite so many of these masculine words. This more inclusive language seems like a good thing to me..

- On the other hand, I think there are limits to how far inclusive language should go. One priest I know never uses a masculine pronoun for God in his homilies, and it sounds stilted. He has to repeat “God” all the time and use made-up words like “Godself” instead of “himself.” It isn’t really our language. If the long struggle we Catholics had getting the liturgy in English means anything, it’s that God speaks to us in our own imperfect language.

Should we call God “she”?

Let’s say the Church someday becomes comfortable with feminine as well as masculine images for God. Can we also use feminine pronouns for God? And can we raise the status of the feminine images; for example, can we also say “Oh Mother” to God as we now say “Oh Father.” Can we mean that literally, not just think of God as a father with motherly characteristics or as mother but only metaphorically? I can only guess at an answer, and my guess is Yes and No.

The “Yes” part is already happening. My friend (of the dinner and wine party) can pray to her “Mother” and think of God as “she.” Feminist theologians say there is a deepening of spirituality when women are free to think of God as one like them. I think the feminine images can deepen men’s spirituality as well.

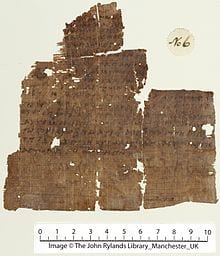

My “Yes” would be a limited one, though. First, much is perfectly appropriate in a person’s private spirituality and prayer. Julian of Norwich, a fourteenth century mystic (and possibly the first person to publish a book in English, Wikipedia says), wrote of God and even of Christ as mother.

You can expand the mind faster than the heart. It’s easy enough to think about God as mother, even if your image of God is very masculine. Saying to God from the heart “Oh Mother” is another story. The Liturgy appeals partly to the mind, but mostly it’s a prayer from the heart. In our hearts we’re not all Julian of Norwich. “She” and “Oh Mother” may work for some in private prayer but not in the Liturgy.

‘Identifying’ with a masculine or feminine God?

I have a second, more serious objection, not to any particular feminine images or to calling God “she,” but to what it might mean in a person’s spirituality. Catholic feminist theologian Carolyn Osiek asks, “Can you [men] identify with a feminine Goddess in the same way that women have been expected to identify with a masculine God?” I don’t know if men identify with a masculine God, but I don’t think they should. “Identifying with” is a modern psychological concept. It doesn’t apply very well to our relationship to God.

God identifies with us, most especially in Jesus. The distance that God traveled from the divine to the human in that historical event completely overshadows the choice of becoming a male human as opposed to a female human. And how odd it would have been if God had decided to become both sexes! Then God would not have identified with anybody.

In a sense we all invent our gods, that is, our favored images of God. But the classic “inventions” of god images, that ones that have kept their power through time and across the world, don’t seem designed to make identifying with God easy. Take the main one at issue here – Father. Could the average dad in Palestine identify with the One Jesus called Father? Jesus described that Father clearly. He’s the one who lets his son take off with an inheritance and welcomes him back with a kiss and a robe and a party. As Pope John Paul II says, that’s more like a mother than a father. And the parable doesn’t help men (any more than women) identify with God. If God is Father, then we’re all on the other side of a relation; we’re God’s children.

Images of God are relational

There are other traditional images that don’t allow anyone to think that he or she is somehow more like God than somebody else:

- the image of the soul as feminine and God as the masculine lover. We find that in the Bible’s “Song of Songs” and also in the writings of many saints, including men.

- and the image of the Church, Pope to bodies in the pews, as bride and Christ as the bridegroom.

God is the male figure, but if I’m touting my own masculinity, the images don’t work at all. There are other classic images that challenge the ways we like to think of ourselves. They effectively stop us from affirming ourselves in ways that divide us from each other:

- the image of us as sheep and Jesus as the shepherd,

- us as clay and God as potter,

- even the image of God as holy and us as sinners.

All of these images involve us with God, but none of them have us quite where we like to think we are. The important thing is they are all relations. Separate yourself from the relation, picture God alone with your favorite image, and you have an idol.

Idolatry

What if potters thought of God as the Supreme Potter but didn’t understand that they were the clay? Or if shepherds imagined Jesus as the Good Shepherd without placing themselves among the sheep? Suppose rulers worshiped the Great Ruler in the sky but didn’t allow that they were among the ruled along with everybody else. That’s idolatry.

There’s a reason why Jesus never called God “the Man in the Sky.” White beard or no, that image is without relationship. It’s just a bare Something all by itself. If you’re also a man, then you might take delight in that image and in your divine-like masculinity. But it’s not Christian.

The classic images, conditioned though some of them are by their time and place and culture of male dominance, put us all–men and women, weak and strong, and so on–in the same position. At times, not often enough but in our better moments, we recognize the privilege of being in that position: To be a recipient of God’s love in its many forms—maternal, paternal, solicitous as a good shepherd, and dependable as a solid rock. To be equal to each other and under the loving discipline of God.

Image credit: Coffee and Canticles via Google Images