God Made All Things, Visible and Invisible – and the Visible Might be the Hard Part

Once I thought that the first paragraph of the Creed, which ends with the words “visible and invisible,” was something you could go along with if you believed in God at all. No Jesus incarnating God, no Holy Spirit, no Blessed Trinity, no Church, only God and, of course, the world. But even among Christians there was an early movement that objected to an important word or two in this section of the Creed. This movement, with an ancient-sounding name, Gnosticism, is alive today.

If God created the world, including all its visible stuff, then some conclusions follow. Neither Christians historically nor the nations of the world today consistently treat the world as if it’s God’s creation. Not everyone goes along with Teilhard de Chardin’s beautiful “Hymn to Matter.” Nor do all people, believers or not, feel like joining St. Francis of Assisi in his love affair with Brother Sun, Sister Moon, Brother Fire, Sister Water, Little Sister Nature, and Brother Ass, his own body.

The Church had to contest early on with despisers of all these beautiful things. That’s a sentiment that continues today in many ways. So this post is about the goodness of the visible, earthy part of the created world. It’s a theme that is becoming prominent among churches in the context of our many ecological crises. Other posts will consider the spiritual side of creation, the “things invisible” of the Creed. For these things I will employ the symbol “angel” and follow the lead of some theologians including Karl Rahner. He insists, if angels are not simply unreal creatures of myth, then they must have essential connections with the world that we see.

Stressing the material world.

In the phrase that closes the first section of the Creed, “maker of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible,” we come to things that are not God. We have to take this not-being-God seriously. The world is the result of God’s free decision to “make” something. The metaphor of making helps us see the freedom with which God acts. Only because this world is God’s free choice can we say God loves the created world.

The Nicene Creed names these things that are not God twice—“heaven and earth…things visible and invisible.” It’s as if the Creed’s authors wanted to be sure we get the point. But which point? Which part of the things that are not God is the Creed most concerned about?

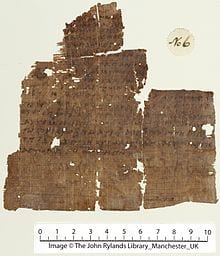

Since this is religion, after all, and since the secular world is familiar enough with earth and visible things, it seems obvious that the Creed would be stressing the heavenly and invisible. In the world of the Creed’s authors, though, the emphasis would have been the other way around. Gnosticism, a philosophy that honored spiritual things and questioned the value, if not the reality, of anything material, was the rage among the intelligentsia. Some Christians proposed that Jesus was a pure spirit, only the appearing to have a body. The true God, in this way of thinking, created only spiritual things. The material world was the work of some evil or maybe only lesser being. Perhaps the God of the Old Testament did it, upstaged eventually by the God of Jesus.

Opposites meet in the movement called Gnosticism

Gnosticism encouraged opposite extremes of behavior. Some gnostics attempted to distance themselves as far as possible from corrupt matter by denying themselves physical pleasures, especially the pleasure of sex. Others, with exquisite logic, felt free to engage in all the pleasures of the body without limit. Our bodies don’t have anything to do with God so God doesn’t care what we do with them. If you produced a child in the process of enjoying bodily pleasures, you just imprisoned another formerly blessed soul in evil flesh. But sex itself, including one-night stands, was no problem.

Other Christians responded: God created this material world and it is valuable in God’s eyes. This became the orthodox, though not entirely consistent, position in Christianity. At its best the Church chose a middle way in its attitude toward material things and pleasures. Enjoy them but don’t let them rule. The Church preaches conditions on our use of the goods of this world: chastity, moderation, days of fasting and abstinence. Living within limits is a way we respect bodily things, including sex.

A new Gnosticism

Part of the world in which this Church exists today, the part with the most of the world’s stuff, is falling into a new Gnosticism. Familiarity breeds contempt, and this world has new ways of showing contempt for material things. It likes consuming rather than the things that it consumes. It prefers getting to having. If it enjoys sex, it also finds ways to turn sex away from pleasure and its natural purpose and toward power, security, and a tool for advertisers. It teaches people not to be happy with their own bodies but to “improve” them according to the latest dictates of fashion. In comparison, the Catholic Church comes off as positively in love with bodily things even when it asks us to make sacrifices and not be caught up in material pursuits.

The Church requires one especially hard sacrifice in this day—giving up work on Sunday. The Sabbath is a gift that the Jews bequeathed to Christianity and the world. Neglecting this gift today flows naturally from a belief that the material world is there only to be worked on, mastered, and put to use. The consequences of this disdain for the intrinsic value of material things are many. For the earth: pollution, exhaustion of resources, extinctions, climate change. For people: isolation and failure of commitment, energy, and insight to do anything about these problems.

Looking ahead

Christianity values the material world more than much of the secular world. That is the theme of this series of posts, but it’s not entirely obvious. Biblical monotheism did away with the many gods of the world. Some say this disenchantment left the world ripe for abuse by us human beings. We took God’s command to subdue the earth and have dominion over it as permission to do whatever we wanted with the natural world. The next post will challenge this interpretation of dominion, but admittedly disenchantment has happened in the Christian world. I’ll look at the way science and disenchantment, for better and worse, took hold. Following posts will offer a kind of re-enchantment by way of finding a place for angels and even devils in the world.