Chapter One, Part One of Torture and Eucharist by William T. Cavanaugh

Torture in Pinochet’s Chile did not only attack individuals. It was part of an assault on society. It aimed to create a certain perception of reality. The state wanted people to imagine enemies, which torture would create and from which the state would rescue society. Torture itself would be one of the necessary means.

On Chapter One, Part One of Torture and Eucharist: Theology, Politics, and the Body of Christ, third in the series on this book by William T. Cavanaugh, a Catholic theologian who writes about the Church and its role in culture, politics, and economics. Introduction to Cavanaugh and links to blogs in the series as they appear are here.

Cavanaugh sets his work in Chile during the repressive years of the Pinochet regime, 1973 to 1990. Before Pinochet started his dictatorial reign and for several years after, the Church in Chile had adopted a form of coexistence with secular powers. Cavanaugh argues that, in confining its work to the soul and leaving bodily matters to the state, the Church became ineffective in both areas. Essentially it consigned both soul and body to a murderous state.

The solution had to be for the Church not only to become interested in bodies but, more, to become a body itself, a social body, with its roots in the Body of Christ, the Eucharist. This, Cavanaugh says, is what the Church eventually did.

Torture and making up reality

The first major section of Chapter One begins, as Cavanaugh says, “abruptly, like the secret policeman’s nocturnal knock at the door.” He gives us a first-hand account of torture.

One’s first reaction is to condemn such a barbarous practice. Less primitive countries don’t do that anymore. Except when they do. Half of the world’s countries engage in torture, and a good many others finance it. (p. 23) And, far from being a primitive practice, modern-day torture follows advanced scientific principles.

Organizations responsible for torture in Chile had names like “National Center for Information.” From that you would guess that the purpose of torture is to gain information. From the Middle Ages to the second Gulf war, that’s an admitted, if rarely achieved, purpose for the use of torture. In fact, some sort of interrogation always accompanied the Chileans’ use of torture. Alas, the goals of torture, as practiced in Chile, were much more subtle than getting information.

The verbal component of torture – and it always has this verbal component – is designed to replace the victim’s reality with the reality of the state. More correctly, with the reality that the state wants to produce. The state is not interested in the true answer to any of its questions but in its answer, one that it makes up:

If you don’t sign this declaration, we will kill your husband or relatives, anyway they’re almost dead but you can save them by signing this declaration that we made. (P. 28, my emphasis. Cavanaugh quotes from archives of the Vicaría de la Solidaridad.)

Creating the individual’s reality is one of the powers this state aggregates to itself. What type of individual does the state want?

Creating enemies

In another book, Migrations of the Holy: God, State, and the Political Meaning of the Church, Cavanaugh describes a common interpretation of the formation of states. There is first a state of chaos. The so-called religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries serve as an example of this chaos. States come along as a response. They replace chaos with order and peace. In Migrations Cavanaugh disputes this analysis as a convenient mythology.

A totalitarian regime such as Pinochet’s in Chile uses a similar and equally mythical analysis. Pinochet’s group took over Chile from the elected socialist Salvador Allende government in 1973. There was almost no chaos after the initial coup. To justify continued totalitarian methods, the state had to manufacture chaos, had to produce enemies.

Interrogation, which always accompanied torture, was not designed to elicit information, at least not true information. The process was designed to get the victim to claim to be an enemy of the state. Having produced an “enemy” the state is justified in using torture to combat the threat. Torture is both the production of that threat and the response to it…. (p. 31)

The next section defines more precisely the type of individual and society the state produced for itself.

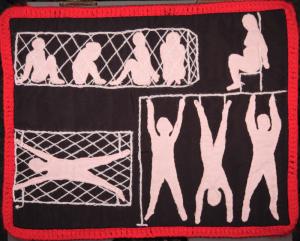

Image credit: Fulltextiles via Google Images