Basil of Caesarea, well-known as a theologian, anti-Arian apologist, and defender of the Trinitarian theology of Nicaea, has a less known side. You can read about Basil’s theology elsewhere. I want to dwell the “city” with his name, Basiliad, and on his achievements as social justice reformer.

This post is in the series “Ordinary Radicals,” heroic men and women described in Common Prayer: A Liturgy for Ordinary Radicals. Common Prayer (January 2 entry) says this about Basil of Caesarea:

Basil [was] an early developer of Christian monasticism, and an incredible preacher and writer. … Basil first left the world to join the monastery, but eventually brought the monastery to the world through the city of Basiliad… This was a giant community of monastic men and women working with doctors and other lay people to provide food, clothing, shelter, and medical assistance to the poor of Caesarea. He later went on to become a priest and a bishop, but he always kept his vision of a monastic life not cut off from the world but embracing the pain and sorrow of the world.

Basil famously wrote:

When someone steals a person’s clothes, we call him a thief. Should we not give the same name to one who could clothe the naked and does not? The bread in your cupboard belongs to the hungry. The coat hanging unused in your closet belongs to those who need it. The shoes rotting in your closet [belongs] to the one who has no shoes. The money which you hoard up belongs to the poor. (Common Prayer)

I had been thinking Basil was exhorting us to give to the poor. Until, that is, I read about Basiliad. Basil was not just preaching charity; he had a better plan.

Basil and “social revolution”

Basil was born into a religiously and politically influential family in Caesarea in modern-day Turkey. Studies and a quarrel with a bishop, who didn’t like Basil’s asceticism, took him away from Caesarea for various periods. Eventually becoming bishop of Caesarea, Encyclopedia Britannica says, he “founded charitable institutions to aid the poor, the ill, and travelers.” With a closer look one can see Basil’s work as essentially social justice. The following information comes from Hektoen International: A Journal of Medical Humanities.

Basil had been preaching to the rich about the sin of hoarding excess wealth. A famine in AD 369 made it clear that charity had to be organized to be effective. Historians “think it likely that Basil had at least a soup kitchen in place by 369.” Undertaking “a much greater expansion in charitable works,” Basil “used the Gospel of Matthew to preach for social reform.” With that encouragement, if not arm-twisting, wealthy people began to support Basil’s “social projects for the poor. This work “challenged directly the hypocrisy, corruption, and uncontrolled self-interest” of the elite.

One sermon criticizes those who “bury your money and despise the oppressed.” Apparently, in Basil’s eyes, the poor were not simply the class who happened to be at the bottom rung of the economic hierarchy. Nor were they at fault for their poverty. They were the oppressed poor. Basil’s work has been called a “major social revolution.”

Basiliad, the “New City”

In Basil’s letters he describes Basiliad, a large complex of buildings centering around a church. The facility lay just outside the city of Caesarea. “Indeed, even when Caesarea itself fell into ruin centuries later, Basil’s neighboring ‘new city’ was still thriving—becoming the modern-day city of Kayseri. Here Basil arranged for the provision of professional medical assistance to the poor.

This New City also provided a safe space for needy travelers and, possibly, a home for orphans. In a letter Basil talks about the Basiliad occupants’ need to “learn such occupations as are necessary to life.” Trade schools were one of the services provided. It’s likely that orphans were recipients of such education. Basil was “teaching the hungry how to fish, not just doling out fish.”

As for the hospital, there is some question whether it was actually the first in the world. Prior institutions cared for the sick. But these did not care for the poor. Andrew Crislip is a researcher on monasticism and medicine. He says a hospital needs three components: “inpatient facilities, professional medical caregivers, and care given for free.” The article in the Journal of Medical Humanities concludes:

It seems that Basil started a new trend. Soon after his death, similar Christian hospitals were sprouting up elsewhere in the Roman empire, and they had become commonplace within one century.9 For these reasons, historians have argued that “the hospital was, in origin and conception, a distinctively Christian institution.”

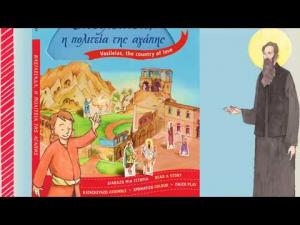

Image credit: Basiliad, the City of Love, on Youtube