Women couldn’t be teachers, at least not of men, in the early centuries of the Christian world. On top of that, St. Jerome, the genius who made the first translation of the Bible into Latin, was entirely too fastidious about contact with women. But Jerome gave in to the request of Marcella of Rome to teach to the community of women she founded. Thus began a long friendship in which teacher and student often traded places. Dr. Joan Ferrante and colleagues at “Epistolae” are my source for this and much of the information that follows.

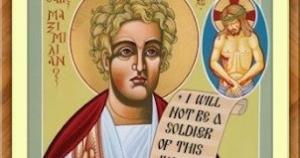

This post is in the series “Ordinary Radicals,” heroic men and women described in Common Prayer: A Liturgy for Ordinary Radicals. Marcella of Rome’s feast day is January 31.

Letters crossing in the “mail”

Most of what we know of Marcella comes from letters Jerome wrote to her or, after she died, to her friend Principia. In the letters (epistolae in Latin, abbreviated “ep.” in the references.) Jerome describes Marcella as a teacher “in the study of scriptures and sanctimony of mind and body.” (ep.65.2) But she was both aware and respectful of restrictions women faced. Jerome says,

She answered any arguments that were put to her about scripture, including obscure and ambiguous inquiries from priests, saying that the answers came from me or another man, even when they were her own, claiming always to be a pupil even when she was teaching, so that she did not seem to injure the male sex because the apostle did not permit women to teach. (ep.127.7)

There must have been a hundred letters between Jerome and Marcella. She says their letters often “crossed.” Only 17 of Jerome’s letters survive, plus the one to Principia. None of hers have survived.

About Marcella of Rome

Marcella, 325-410, was high-born. Consuls and prefects were family members. In their home on the Aventine, one of Rome’s seven hills, she and her mother, Albina, established a women’s religious community. A cousin was a close friend of St. Jerome’s.

Marcella married, but her husband died after only seven months. Young and “distinguished for her beauty” she attracted men, including an old man named Cerealis. He was a wealthy consular and persistent suitor. He “offered to make over to her his fortune so that she might consider herself less his wife than his daughter.” Marcella answered:

Had I a wish to marry and not rather to dedicate myself to perpetual chastity, I should look for a husband and not for an inheritance. (“On this day: St. Marcella of Rome,” in National Catholic Reporter)

Marcella practiced austerity already in adolescence, Jerome says in ep. 127.6. Well-educated from her youth, she especially liked Plato’s comment that “philosophy is a meditation on death.” That austerity along with their connection through Marcella’s cousin no doubt made things easier for St. Jerome. The Epistolae site says Marcella “overcame Jerome’s hesitation to meet the eyes of noble women by her industry, so that it was she who enabled him to make the contacts with those women who would be so important for him.”

In her letters Marcella so peppered Jerome with questions that he had to write hastily to keep up. Jerome the Latin stylist explains he knew “she was more concerned with answers than with polished style (ep. 29).”

Charity onto death

Besides her intellectual prowess, Marcella was a model of Christian charity. Born into wealth, she gave away the riches of her estate to assist the poor. Jerome writes,

Of gold she would not wear so much as a seal-ring, chosing to store her money in the stomachs of the poor rather than to keep it at her own disposal. (“On this Day: St. Marcella of Rome”)

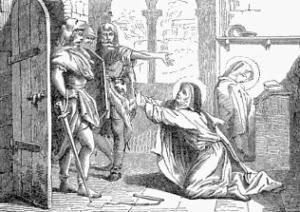

Indirectly this charity led to her death in 410 during the seige of Rome led by the Visigoth King Alaric. Invading soldiers entered the home on the Aventine. They demanded riches, but Marcella told them there were none. Angered, they scourged her and beat her with cudgels until the arrival of other soldiers with “some reverence for holy things.” Jerome’s narrative continues:

They escorted the two women [Marcella and Principia] to the church of St. Paul—one of those which had been named by Alaric as a sanctuary for all who chose to take advantage of it. Here the venerable Marcella, exhausted with here fatugues and wounds, died the next day. (“On this Day”)

Image credit: “The Monstrous Regiment of Women: Marcella of Rome,” by Christine de Pizan