My parish, St. Raphael’s in Springfield, Minnesota, has begun an adult education course on the Nicene Creed. We are listening to and discussing a series of video lectures by Bishop Robert Barron. (From Word on Fire: The Creed) The bishop’s first talk took us all the way through the first three words of the Nicene Creed. There was enough material there for some serious thought.

The Nicene Creed begins

I believe in one God, the Father almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible.

Bishop Barron starts out by noting that not every religion has a creed. Christianity does, and it has an important place in our faith lives. That says something distinctive about the Christian faith.

Christianity is more than an attitude toward life and a way of acting. Christianity tells us about the world, ourselves, and God. Christians make claims, and what we say is either true or false. We commit ourselves to defending these claims when we propose a creed to the world.

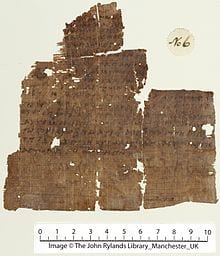

In the fourth century, some 300 years after Jesus lived, died, and rose, the Church knew it needed an official statement of what Christians believed. The Nicene Creed, worked out in theological debate and through two ecumenical councils at Nicaea and Constantinople, answered that need. Since then practically every Christian denomination expresses its faith with the Nicene Creed.

The first word, “I/We”

In the 1970’s the International Commission on English in the Liturgy adopted a translation of the Nicene Creed. This was the first English version of the Nicene Creed that I learned to recite in Church, and it differed from the Latin text. Mostly it was an attempt at more everyday English rendition of the same ideas, but one change was substantial. It changed “I believe” (Credo in Latin) to “We believe.” In 2011 a Vatican commission reversed this change, along with others. We now say, as the priest did before in Latin, “I believe.”

Bishop Barron discusses this issue and notes that the original Greek text, dating back to the fourth century, says “We believe,” not “I believe.” (Pisteuomen, not Pisteuo, in Greek.) The logic for “We” is twofold. First, and most obviously, in church we are professing this faith together. Second, it’s not as if we come by faith on our own. As Catholic theologian David Tracy says, we believe with the apostles. Or, as I like to say in private prayer:

I believe with the Communion of Saints on earth and in heaven, the Catholic Church; with apostles, martyrs, teachers, and all who encourage me by word and deed; and with the ones who passed on both faith and life to me, Dave, Rose Marie, and all my forebears.

I don’t believe on my own say-so.

But the “I believe” formula has a long tradition in liturgical use. It goes back even farther than the Nicene Creed. From very early times a candidate for entry into the Church would recite a creed at his or her Baptism. He or she would start by saying “I believe.”

Barron believes both forms are important, but I get the impression he would prefer the “We” form at Mass.

The second word, “believe”

Atheists, says the bishop, make an unwarranted criticism of Christian believing. They contrast faith and the knowledge that science procures. As if faith is taking a position arbitrarily, and knowledge is believing with evidence. Actually, nobody lives without a kind of faith guiding most of the things they believe. We rely on the experience of others whom we trust to tell us the truth, whether it’s the backyard gossip or a school textbook.

Our personal relationships depend on faith, especially when that’s a relationship of love. I had gathered a lot of factual, evidence-based knowledge about the person who became my wife, and she about me, before we entered into marriage. All that evidence didn’t add up to proof that she loved me or even that I loved her. Nothing in my experience could ever allow me to say, with the kind of evidence one looks for in science, that loving another person is even possible or reasonable. But what would life be like without the leap of loving commitment?

Barron says faith is not the same as knowledge. But it is not less than knowledge.

The third word, “in”

Like Bishop Barron I make a big deal out of this little word, “in.” I think about someone saying, “I believe in you.” When we say “I believe in God,” it’s like that. Unlike believing a mere fact, it involves one personally. Believing in someone is much more than believing that he or she exists.

The bishop gives this personal involvement some grammatical support from the Latin language. Latin uses the same word, “in,” for both “in” and “into” in English. Speakers of Latin differentiated the two meanings by the endings of the nouns that follow. Latin is a highly inflected language. Endings of words, or inflections, carry specific meanings. One ending implies static presence, in this case “in.” A different ending implies movement, “into.” The Creed in Latin begins “Credo in unum Deum.” The word for God, “Deum,” has the ending that implies movement.

According to the Christian Creed, believing in God isn’t an armchair exercise. To believe is already to start moving on a path of personal involvement. We believe into God. We enter into God’s story when we recite the Nicene Creed at Mass.