William R. Herzog II says he wrote a book about Jesus’ parables after puzzling about the parable of the Laborers in the Vineyard. My dad once told me how he felt about that very parable. It wasn’t just. The landowner should not have paid laborers who worked all day the same wage as those who only worked one hour. I could easily understand. Dad was a banker; financial doings were important to him. My response, which I don’t remember after all these years, probably appealed to the spiritual meaning of the parable. When it comes to God’s grace, human merit has no claim. We are all unworthy. God can be generous to anyone, and no one has any business complaining.

What if Dad was right not to like this parable? Jesus’ audience might not have like it either. Maybe Jesus was trying to make them think harder than they were comfortable with, not about grace, but about the oppressive conditions under which nearly all of his listeners lived.

That is the kind of interpretation William Herzog aims at in Parables as Subversive Speech: Jesus as Pedagogue of the Oppressed. He works against the traditional view of parables as “earthly stories with heavenly meanings.” (Chapter 1. See note below.) In a previous post I came to the same conclusion, writing about some of the parables in Mark. In some of these parables, I opined, “the meaning as well as the tone is quite earthly.” Parables are narratives or pictures that leave one wondering about how to apply them. Thus they stimulate active thought. Herzog asks, What if the deeper thinking Jesus was pulling his listeners toward was about things more earthly than heavenly.

In this and future posts I will be following Herzog through several of Jesus’ parables.

William Herzog, Paulo Freire, and the pedagogy of the oppressed

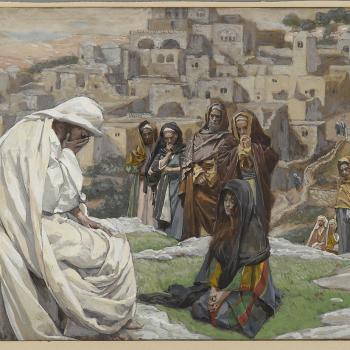

Jesus parables are mostly pictures of everyday life, which we like to think of as metaphors for more abstract moral or theological truths. Herzog asks, What if the parables are simply what they sound like? Specifically: what they must have sounded like to peasant laborers under the thumbs of foreign and domestic elites.

To better understand this situation of Jesus and his peasant listeners, Herzog adopts a model that theologian Paulo Freire proposed. Freire worked in a situation similar in some important respects to Jesus’. Paulo Freire was teacher and activist in support of poor and oppressed people in Brazil. The model that Freire embodied and Herzog applies to Jesus is: “pedagogue of the oppressed.”

Developing a model, William Herzog says, keeps an interpreter aware of what otherwise might be hidden biases. But the model, or exposed bias if you will, must be tested. For Herzog the test is whether or not the model—Jesus as pedagogue of the oppressed—helps to interpret several parables. Does it clear up some puzzles that bedevil more usual ways of interpreting parables? Herzog tries his model out on nine parables, a limited but significant selection.

Interpreting biblical literature

There’s more than one way to interpret the Bible, and William Herzog has chosen a method that is not the most recent. He explores the situation in which Jesus ministered, including its economic, political, and religious context. He tries to uncover the actual words of Jesus behind passed-down memories and the sometimes spiritualizing interpretations of the biblical authors.

As a Catholic Christian, I must pay attention to the stories as they appear in the Bible. The interpretations of the Spirit-led authors of Scripture are important. So is the way the text challenges me in the 21st century. Some of the most recently developed methods for interpreting delve deeply into the meanings of the text just as we find it.

But a foundational Christian belief is that God entered history. God became a historical person, to which Scripture gives witness, but not always clearly and straightforwardly. I don’t know which is more important, the revelation that the words of Scripture inspire in the receptive reader or the revealing in what has been called the “quest for the historical Jesus.” But I’m sure that we increase our understanding of God when we attempt to uncover that history behind the Bible. Besides, it’s a fascinating study and worthwhile even for the contribution to understanding our world that all history makes.

The next post will explain in more detail the “pedagogy of the oppressed” model. Herzog dives into the history, sociology, politics, economics, and religions of Jesus’ era to help understand the parables. I will indicate why that approach to me seems likely to bear fruit. The real test will be in the parables themselves. They’ll be the focus of following posts.

Image credit: Westminster/John Knox Press

Note: References will cite chapters instead of page numbers because I’m working with an online version of Herzog’s book.