Reading Parables as Subversive Speech, I’m letting William Herzog challenge my older reading of many of Jesus’ parables. Those down-to-earth stories might not be earthy metaphors for a far-off heaven, as often supposed. They could just be stories about day-to-day life on earth. The Parable of the Laborers in the Vineyard begins, “The kingdom of heaven is like….” But that may be the Gospel writer Matthew’s idea and not part of Jesus’ parable. Or, if it is, it might be Jesus simply being ironic, Herzog says. The life pictured in the parable doesn’t seem much like heaven.

In Part Two of his book, William Herzog tests the model of Jesus as “pedagogue of the oppressed” (teacher of Palestine’s poor people) that he laid out in Part One. (See this post.) The Parable of the Laborers in the Vineyard in Herzog’s Chapter 5 poses the first test. (A note at the end explains why I don’t give page number references.) Is this parable about the surprising way God deals with people in the kingdom of heaven? That’s Matthew’s idea, and practically every interpreter since agrees with Matthew in one way or another. But maybe the story’s picture of life in the midst of oppression is actually about life in the midst of oppression.

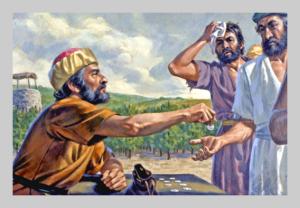

The parable doesn’t say, exactly, that it’s about oppression. A landowner sends laborers into his vineyard to gather the harvest. Groups are sent at different times of the day. The earlier ones work the whole day or most of it. The last work for only one hour. All get the same pay. The question we readers often ask – and the first group of workers posed it as well – isn’t about systemic oppression. It’s simply, Is that fair? Do the ones who worked the whole day have a legitimate complaint against their employer?

The landowner justifies his action and accuses the grumblers of being envious. Essentially he says, “I gave you a fair wage. As for these others, I can do what I want with my money.” The traditional interpretation takes the landowner’s side and criticizes the complainers. Herzog says that’s blaming the victims.

Earlier posts in this series

- William Herzog Reads Jesus’ Parables, Brings them Down to Earth

- Paulo Freire, the “Pedagogue of the Oppressed”: Is This a Good Fit for Jesus?

Traditional interpretation

The Parable of the Laborers in the Vineyard appears only in the Gospel according to Matthew. Matthew tells us that the parable is about one of Jesus’ favorite themes, the kingdom of heaven. This move makes the landowner a God figure. The daily wage that the laborers receive is grace, or salvation, or membership in the community of Jesus’ followers. God distributes grace based not on human merit but on his own will to save all people. God accepts with equal favor those who have “born the burden of the day’s heat” and those who worked only one hour. The parable criticizes the complainers for trusting in their own merits rather than God’s grace.

Looking deeper, interpreters following Matthew find analogues for the various groups of laborers sent at different times. The first groups represent the original members of Matthew’s community, Jews, who were the first followers of Jesus. The last groups would be Gentiles who have joined the Jesus group more recently. Matthew’s story argues that Jewish members should accept Gentiles as equals even without their having to “bear the burden” of Jewish circumcision and dietary laws. (Some Jewish members must have been grumbling about the Gentiles.)

The lesson is not just for Matthew’s community; it has universal application. Matthew sums up the lesson twice with a saying about the first and the last. He begins the parable immediately after Jesus ends a different lesson: “But many who are first will be last, and the last will be first.” And in the parable Matthew’s Jesus concludes: “Thus the last will be first, and the first will be last.” So we learn not to be like the grumblers in the parable, not to focus on our own merit or compare ourselves with those we might deem less worthy of God’s grace. We are not made righteous by our works but only by God’s grace.

We can certainly thank Matthew for this inspiring, inspired lesson. But was it the same lesson Jesus taught?

Dramatis personae, 1: The landowner

The interpretation of the landowner steers Jesus’ parable in one direction or another. Does the landowner represent God as traditional interpretation has it? Herzog says, Let’s first find out about real owners of land in Jesus’ time.

In first-century Palestine rich persons owned much of the land, but poor peasants could have their own land. Was the landowner in the parable a wealthy businessman or a poor peasant? With some key details Jesus lets us know that the landlord was rich. He was rich enough to have a servant, a foreman, who doles out the wages. The fact that this parcel of land was a vineyard also indicates much wealth. A peasant would not put his field into grapes. He’s too interested in mere survival to commit the necessary four years to developing a luxury crop like grapes. This landlord has put survival worries behind him. He has many fields, enabling him to devote some of them to a crop that he knows will yield a healthy profit in time.

The landowner came to possess all those fields the same way financiers have preyed on the poor through the ages — through hostile takeovers. He foreclosed on loans that peasants had to take out, with their fields as collateral. Today we’ve almost forgotten how to lament the loss of small family farms; it’s been going for so long. First-century Palestinians experienced – to the profit of some and the ruin of many more – a similar commercial dynamic.

This is the picture of Jesus’ rich landowner that Jesus’ listeners would have had in mind. Herzog asks us to think whether Jesus would use a capacious loan shark as stand-in for God.

Dramatis personae, 2: the laborers

Some of Jesus’ poor listeners probably belonged to the same socio-economic group as the laborers in Jesus’ story. Not just workers like employees of today. These were day laborers, a class well below that of peasantry. A peasant farmer who lost his land might end up as a day laborer. His other option, only slightly better off than a day laborer, would have been artisan, a maker and seller of crafts. Joseph and Jesus during his “quiet” years may have been artisans.

Day laborers, as the name implies, worked for a day if they were lucky enough to have somebody hire them. The typical daily wage, one denarius, was barely enough to feed a family for a day or two. But day laborers didn’t work every day. When it wasn’t harvest or planting time, there was little work available. They had to beg or starve or both. Needless to say, they didn’t have families. Once reduced to the ranks of the day laborers, a man’s life was short – five to seven years, Herzog says.

Still, there was always a plentiful supply of day laborers, fed not only by peasants who had lost their land but also by these farmers’ excess children. A small farm could support only so many.

The parable Jesus told vs. the parable in the Bible

Our Bibles give the Parable of the Laborers in the Vineyard 16 verses. Modern scholars generally say that in the parables the Bible comes very close to the actual words of Jesus. That still leaves some room for adjusting what the Bible reports.

William Herzog adjusts less than some. He agrees with the majority that Verse 16, “Thus, the last will be first, and the first will be last,” does not belong to the parable. (Most likely Jesus said these words some other time.) And the first part of Verse 1, Verse 1a – “The kingdom of heaven is like …” – he thinks, probably does not. Here is the parable as Jesus, more or less, may have spoken it:

The Parable of the Laborers in the Vineyard (Matthew 1b-15)

A landowner went out at dawn to hire laborers for his vineyard. After agreeing with them for the usual daily wage, he sent them into his vineyard. Going out about nine o’clock he saw others standing idle in the marketplace, and he said to them, “You too go into my vineyard, and I will give you what is just.” So they went off. And he went out again around noon, and around three o’clock, and did likewise. Going out about five o’clock, he found others standing around, and said to them, “Why do you stand here idle all day?” They answered, “Because no one has hired us.” He said to them, “you too go into my vineyard.”

When it was evening the owner of the vineyard said to his foreman, “Summon the laborers and give them their pay, beginning with the last and ending with the first.” When those who had started about five o’clock came, each received the usual daily wage. So when the first came, they thought that they would receive more, but each of them also got the usual wage.

On receiving it they grumbled against the landowner, saying, “These last ones worked only one hour, and you have made them equal to us, who bore the day’s burden and the heat.”

He said to one of them in reply, “My friend, I am not cheating you. Did you not agree with me for the usual daily wage? Take what is yours and go. What if I wish to give this last one the same as you? Am I not free to do as I wish with what is mine? Are you envious because I am generous?”

The parable that peasants and day laborers may have heard

Herzog puts Jesus’ words into Jesus’ own world. Jesus didn’t speak to the ages or to Matthew’s community but to people of the third decade of Century One. He was one of them. He knew how they thought and how they would understand and feel about his stories. What they would have understood must be what Jesus meant. Imagine being there and hearing the Parable of the Laborers in the Vineyard:

- “A landowner goes out to hire laborers.”

That’s wrong. (You’re thinking.) Everybody knows a rich landowner wouldn’t be caught dead associating with laborers. They send servants to do their bidding. What’s Jesus up to?

- “He agrees with them for the usual daily wage.”

As if a day laborer can bargain with the powerful rich. Nonsense!

- “I will give you what is just.”

Is anything in these times just?

- “Why do you stand here idle all day?”

That’s insulting. It’s not like they’re choosing not to work.

- “Give them their pay, beginning with the last and ending with the first.”

Another insult. The first laborers should get paid first.

- “Each of them got the same wage.”

He makes the first laborers watch the others get paid. Then he dashes their hopes for more. That’s the worst insult, but what do you expect from the rich?

- “They grumbled against the landowner.”

What else could they do but stand up for their honor, even though it’s hopeless?

- “My friend….”

Friend, my eye! He picks on one worker to make an example of him.

- “Take what is yours and go.”

He’ll never again find work in this district. Others, take warning.

- “Am I not free to do as I wish with what is mine?”

We know how you got all that you call yours.

- “Are you envious because I am generous?”

Generous? One stinking denarius!

Honor and shame

The job of what Herzog calls pedagogue of the poor is to bring people to a deeper understanding of facts they know all too well. Not all the above imagined responses to Jesus’ story are available to many of Jesus’ listeners. At least not consciously. Sociologists say oppressed people tend to take in, internalize, the worldview of their oppressors.

That explains Herzog’s surprising statement about Jesus’ peasant and day laborer listeners. He says they probably approved the landowner’s high and mighty attitude toward the story’s grumblers. After all, he is high and mighty. Day laborers are lowly in both circumstance and esteem. In first-century Palestine, the honor/shame regime has operated for so long that it seems like reality. A socially constructed reality, but as real as anything in the minds of all, poor as well as rich.

As a result, poor people must cling to what little honor they have, even if only the monetary value of their muscle. A few can hope to join the next level up in society, the “retainer” class. They would do society’s dirty work, relaying orders and collecting fees, rents, debt payments, and taxes. They would be the most hated of men, but it would be a living. If they were clever and strong, they might even collect enough extra for themselves to become rich — at the expense, of course, of their poor former compatriots.

At the opposite extreme, the honor/shame system obliges the rich to compete for honor. This comes from displays of wealth—conspicuous consumption. They must live in gated houses, wear expensive purple, dine on calf and lamb, separate themselves from the poor. To fund the show, they must extract as much from the poor as possible. In a zero-growth economy you become rich by making somebody else poor.

Religion and Scripture

Unequal societies find ways to justify the present distribution of wealth. For this purpose religion comes in handy. As the heavenly realm is high above the earth, so certain privileged classes are high above others.

Priests and other rich Judeans found one strain of their Scriptures especially useful. The holy texts contained many passages about purity. We find rules about diet, contact with dead things and certain animals, diseases and disabilities. There are things you can mix together and things you can’t mix. Women and their monthly flow and sex are big issues. The last mentioned makes a man impure for three days. In many cases, however, the path from impurity to purity is more complicated, including sacrificial offerings in the Temple. Following the ins and outs of the purity regime was next to impossible for a poor person. Hence, the common designation of the poor as sinners.

For Jesus a different set of passages had more weight. These were the Scriptures that cried out for justice for the poor, the widow, and the stranger. They demanded periodic forgiveness of debts and redistribution of lands, rebalancing the economy and reversing the natural upward flow of money. (Would that we had such mechanisms!) The Judeans had all this on record, but the powerful attended to these commands only to ignore or work around them. These are the Scriptures that were close to Jesus’ heart and often on his mind.

Consciousness raising

Jesus’ Parable of the Laborers in the Vineyard never told his listeners what to think. But it was devastating in its description of the real life of a day laborer or anyone who knew he might become one. It was bound to spark discussion. For every three listeners there would be four or more opinions clamoring to be heard. At that point, if Herzog’s model of pedagogue of the oppressed is correct, Jesus would let go of control of the debate. He’d let his listeners think for themselves. That’s how education of oppressed people should work according to scholars like Herzog’s guide, Paulo Freire. (I introduced this writer and “pedagogy of the oppressed” here.)

Is that what Jesus wanted? To get the poor of Judea to start thinking on their own about their lives, about justice, about God’s will? It’s a challenge to traditional ways of interpreting the Parable of the Laborers in the Vineyard. But Herzog’s view does have one thing going for it. If that’s what Jesus wanted, he could hardly have told the story better.

Jesus had more stories to tell, and William Herzog considers nine altogether in Parables as Subversive Speech. This first parable is one of five that, Herzog says, “codify” the experience of Judea’s impoverished and oppressed. In Part Three a further four parables, in his words, open up new possibilities and challenge limits. These parables and Herzog’s interpretations will be the subjects of further posts in this series.

Note: I’m working with an online version of Herzog’s Parables as Subversive Speech so I can’t reference page numbers.