The story the Bible tells is a story of monotheism from beginning to end. But that does not reflect the real history of the Jewish people. For them monotheism only gradually became the general rule. The process started with the novel idea of a god of history, then developed into a whole new mindset about history and reality.

This is the eighth in a series on the Creed of Christians. An introduction consists of my retelling of the Creed’s story. That and links to other posts in the series are here.

The change that the Jews accomplished, abandoning all gods but one and rejecting the cyclical worldview of all their neighbors, must have been difficult. The Israelites knew how others lived. To their neighbors belonged the familiarity of a world of repeating cycles. The new insight of the Jews was less comfortable and sometimes hard to believe:

Vanity of vanities, says Qoheleth, vanity of vanities! All things are vanity! … One generation passes and another comes, but the world forever stays. The sun rises and the sun goes down; then it presses on to the place where it rises. … What has been, that will be; what has been done, that will be done. Nothing is new under the sun. (Ecclesiastes 1:2-9)

You can see that, unlike the Pagans, Jews, or some of them, hated this feeling. But their God also said, in the words of the prophet:

See, I am doing something new! Now it springs forth, do you not perceive it? In the desert I make a way, in the wasteland, rivers. (Isaiah 43:19)

I think Israel’s amazing, if not miraculous, beginning had something to do with their belief that God could do new things in history.

A rocky career for Israel

That beginning wasn’t the only new thing “God,” in this interpretation of history did for and to Israel. In the year 587 BCE Israel disappeared as a nation, and about 40 years later it came back to life again. Here are some facts about Israel’s history between its birth and this rebirth:

- There was a period during which Israel was only a loosely knit conglomeration of tribes without a central leader. (Late 1200’s to late 1000’s B.C.E.

- David and Solomon succeeded in establishing a united and fairly prosperous kingdom. (1000-931)

- Archaeological remains and the biblical record both show that monotheism wasn’t quite the norm. The worship of gods other than Yahweh was going on during these periods. Solomon set up shrines to foreign gods. I suppose that was partly to keep his many foreign wives and girlfriends happy, but certainly it was also a way to conduct affairs of state—good foreign relations.

- After Solomon the kingdom split in two. There was a larger Northern Kingdom, usually called simply Israel, and a Southern Kingdom consisting of the Tribes of Judah and Benjamin, called Judah. Jerusalem was the capital of the Southern Kingdom. The two kingdoms were usually hostile to each other.

- Neither kingdom was consistent in the exclusive worship of Yahweh. Prophets dared to oppose political and economic powers with the word of Yahweh, but there were false prophets, too.

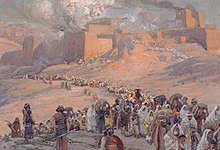

- In 722 Assyria conquered the Northern Kingdom. In 587 Babylon finished off the Southern Kingdom. They forced the king, whom they blinded, and the elite of the people into exile. This, the Babylonian Captivity, was the end of the nation of the Israelites.

What comes after the end?

I suppose you could consider this a success story.Monotheism was barely started, but Israel lasted almost 500 years. Compared to Egypt that’s not much, but it’s twice as long as U.S. history. The ones in exile couldn’t see it that way, though. They had been God’s people, but now they were no longer a people. God had been active in their history, but now their history was over. They had risen and fallen in apparent obedience to the cyclical pattern of all the rest of the world.

What could the people possibly believe about God in a situation like this? What kind of vision of themselves could they have now? How could they continue to trust? Why should they be faithful to Yahweh now that their story seemed to be over?

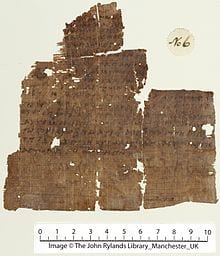

These Israelites continued to be a distinct people even in exile in a foreign land. That fact, I think, is almost as miraculous as their birth as the Bible tells it. Without land or temple the Jews became people of the book. Synagogue services based on readings from sacred texts may have started around this time. It was a time of collecting, editing, combining, rewriting, and composing texts.

Jeremiah and other prophets interpreted anew the Jews’ history as God’s people: When they were faithful to God and God’s commands, God favored them. When they were unfaithful, which seems to have been most of the time, God punished. Most important, when they repented and turned back to their covenant with God, God was merciful. This pattern occurs over and over in the sacred writings, most of which were put into final form around the time of these huge defeats or later.

Monotheism: One god for all the nations

According to the new interpretation, God wasn’t showing weakness compared to other gods when Israelites suffered. The suffering was God’s punishment, and God’s instruments for punishment included the hated Assyrians and Babylonians. That meant God was more than a tribal deity. God was actually using other nations, whose own gods turned out to be irrelevant. That might not have seemed like such good news. A person might have preferred to be free of God’s interference. But for the Jews it saved their identity as a people.

The Israelites might have given up on their national god and gone wholeheartedly into the service of a more powerful god of a more powerful nation. They had done that before in less dire circumstances. Instead they reached for a god not limited to any one nation. In a crucible where torture and death could be the price for faithfulness to Yahweh, Jews began to think of the foreign gods as no gods at all. Monotheism was born in agony. It was about this time that the people began to be called Jews.

While Israel was still a going concern, the story was about Israel and Israel’s God. In the aftermath of national tragedy, the Jews’ story couldn’t remain the same; it had to die or grow. The Jews kept their story alive by expanding it to the world. God became the god of all the nations.

History is God’s story.

The new thing that the Jews added to our understanding of our lives and our world is that meaning is found not just in the regularities, the repeating patterns, the laws of nature but also in history. History is not just one thing after another and not just a repetition of the same things over and over. History, as the Jews conceived it, has a new kind of meaning; it’s a story. History goes from somewhere to somewhere else. New things happen in history.

There was no historical or psychological necessity for the Jews to take this step, but there is a kind of narrative necessity, after the fact, in the story of a historical god. Psychologically, the Jews may have wanted to switch to a more powerful god. History would seem to dictate that the nation that ends up on top gets to keep its story intact. But at least some Jews, perhaps realizing that no nation stays on top forever, decided against a temporary fix. They leaped with both feet into the story itself, the story of a historical God, and history as God’s story. It could no longer be a story of any one nation; it had to be universal. The God of such a story had to be not just Israel’s but everyone’s.

Image credit: Wikipedia