India strikes nine sites in Pakistan with missiles to avenge the terror attack in Kashmir. On Tuesday, this was the lead story in much of the American media. But two weeks ago, when 4 terrorists killed 26 male Hindu tourists in the scenic spot of Pahalgam after identifying their religion, the horrific massacre barely registered here.

India has said the military operation was precision-targeted against the terrorist hideouts in Pakistan-administered Kashmir and Punjab, was not against army positions and was non-escalatory. Pakistan said at least 20 civilians were killed in the strikes and called it an act of war. Islamabad has claimed shooting down some Indian aircraft involved in the operation. A day after, one only hopes the escalation of hostilities does not lead to an all-out war between two nuclear-armed neighbors.

“What a shame!” President Trump remarked when informed about the Indian missile strikes, adding, “I hope it ends very quickly”. Indeed, war is not good for either side, and there is (almost) never a ‘just’ war. But what were India’s compulsions?

I attended a vigil over a week ago on Long Island in New York to mourn the victims of the terror attack on April 22. It was organized by the local Indian community. From what people said from the podium, I sensed there was palpable anger and agreement with India’s position that the attack was most likely aided and abetted by Pakistan, even though New Delhi did not present any proof. However, in the past, links to terror attacks on India were often boasted by Pakistani leaders, justifying the policy to protest Indian occupation of the disputed territory of Kashmir, called the Switzerland of the subcontinent.

The calls for revenge from the Indian community in America have been stronger because it was the first time that terrorists had singled out Hindus, perhaps to inflame Hindu-Muslim tensions. (It did not transpire thankfully as even Kashmiris of all stripes condemned the massacre.) You can imagine the sentiment back home in the Hindu majority nation. The Indian government, led by the BJP, a Hindu nationalist party, had to act in some manner in retaliation. The May 6 midnight Operation was codenamed Sindoor, the vermilion powder many married Hindu women wear in their hair parting, referencing the Pahalgam widows.

Islamabad’s position that Pahalgam was a false flag operation did not wash. However, some reputable Muslims from Kashmir I know here did question how the terrorists could carry on the massacre unimpeded in broad daylight at a popular tourist spot in a tight-security zone. It was a serious security lapse, to say the least.

That it was a mere act of terror did not wash either, said an Indian diplomat from the New York consulate at the vigil. It was a conspiracy, he hinted, to derail Kashmir getting back to normalcy after decades of insurgency and when tourism was coming back. Maybe that is what the terrorists and their minders did not like. They also wanted the attack to be seen as a protest against what they claimed was Hindus from outside being settled in the Valley to change its population mix. Kashmiri Hindus (also called Kashmiri Pandits), on the other hand, have nursed a strong resentment that they were hunted out of their native places in the valley in an exodus in the early 1990s.

There is a long history of hostilities over Kashmir and allowing self-determination for Kashmiris. After India’s partition in 1947, both countries have laid claim to the coveted territory, but have only parts in their control. They have fought three wars and come to the brink a few more times.

The worst terror attack in India’s history – its own 9/11 – took place in November 2008, when 10 members of Lashkar-e-Taiba, a Pakistan-based Islamist militant organization, carried out 12 coordinated shooting and bombing attacks lasting four days across Mumbai, including in the storied Taj Mahal Palace hotel and a synagogue. A total of 175 people died, including six Americans and nine of the attackers. Extreme restraint was exercised by the party in power then, Congress, which was shaped by leaders like Mahatma Gandhi, the Apostle of Peace, before Independence. Pakistan condemned the attack, admitting that one survivor was its citizen.

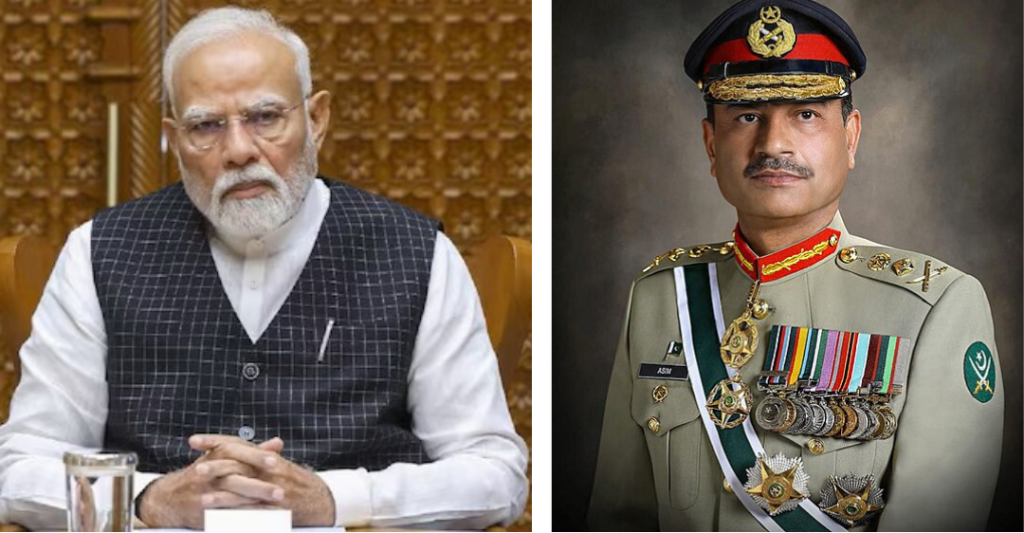

The newest provocation for Islamabad has been the fact that India, ruled by a strong leader, Narendra Modi, since 2014, unilaterally ended in 2019 the autonomous status given to Kashmir under Article 370 of the Indian Constitution. New Delhi said it corrected a historical blunder. Islamabad said it was tantamount to annexation.

In the last fortnight, while Prime Minister Modi was promising strong action, New Delhi also employed non-military actions to avenge Pahalgam. Most importantly, it suspended the Indus Water Treaty, which means India can shut or open at will the spigot of water of rivers that flow down to Pakistan. Islamabad called it an act of war and threatened legal action internationally.

The best we can hope for at this stage is a repeat of 2016, when India launched a ‘surgical strike’ inside Pakistan territory, attacking a terrorist camp after its military base in Kashmir’s Uri was attacked by terrorists. Escalation was wisely avoided by both sides in the aftermath.

But this time, containment may be challenging. Indian media has dubbed Pakistan army chief General Syed Asim Munir as a ‘Jihadi General’. The New York Times profiled him three days ago as the most powerful man in Pakistan. Not unusual for a country where the military has called the shots most of the time from behind the scenes and generals have staged coups and ousted elected governments.

General Asim Munir has used provocative language. He said, “Kashmir is the jugular vein of Pakistan,” borrowing from Mohammed Ali Jinnah, architect of the two-nation theory (a Muslim Pakistan and a Hindu India) whose obduracy led to the bloody partition in 1947 after two centuries of British rule and ended up in the largest ever movement of population in world history. The cleaving still left a sizeable Muslim population in India, currently at 14% of the total. India is still a secular state and Bangladesh breaking away from Pakistan in 1971 made a mockery of the two-nation theory. All eyes are on General Munir, as he may shape Islamabad’s response to Indian strikes.

India, the land of Buddha and Mahatma Gandhi, has historically been a peace-loving country. It does not attack other countries except when provoked or in self-defense. But vis-à-vis sworn enemy, Pakistan, and its purported state policy of terror, the attitudes in India have been hardening.

Independent analysts have said continuing hostilities are going to hurt Pakistan more, which has a fragile economy. The balance of power is skewed in India’s favor – India’s economy is nearly 10 times larger than Pakistan’s. It has much more firepower for a conventional war. Its clout as a world power has been rising. It has tactfully managed to remain friends with both the USA and Russia. With China, its relations have not been good as Beijing and Islamabad are close.

A nuclear conflagration in the subcontinent is the worst-case scenario. Worried, world leaders have advised restraint on both sides. Former Pakistan ambassador to the United Nations, Maleeha Lodhi, has said she foresees intervention by Washington, DC to defuse the situation. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has spoken to his counterparts in both countries and said on X, “I will continue to engage both Indian and Pakistani leadership towards a peaceful resolution.”

India has said it has acted in the way it needed to. Now it has to be seen whether Pakistan also calibrates its countermove to tamp down the temperature and yet save face in front of its people. Pakistan’s Defense Minister Khawaja Muhammad Asif has warned that India’s latest assault marked an “invitation to expand the conflict”, but cautioned that Islamabad is “trying to avoid” a full-fledged war.

Finally, I quote the late Urdu poet Sahir Ludhianvi, celebrated on both sides of the tempestuous subcontinental border:

Jañg to ḳhud hī ek masala hai, jañg kyā masaloñ kā hal degī.

War itself is an issue; how will it resolve problems?