IN THE MIDST OF THE SEVEN CANDLESTICKS.

~

Alexander Svoboda had wandered Asia and the vast Ottoman Empire for many years, and, being a jealous man, could claim, with pride, to be the first to photograph the caves of Elephanta and the monument of Ctesiphon. No place in the world, however, seemed so remarkable for its natural phenomena as Hierapolis. Together with his friend Barth, who had joined him from Smyrna, he wandered among the tapestry of ruins in the quilt of the “holy city.” It was a testimony to the supra-cultures of empire. Was it Europe or Asia? Was it Ottoman or Greek? It was what is was, just like the artist in pursuit of its mysteries.

Alexander Svoboda.

Svoboda, born in Baghdad in 1826, was the son of Anton Svoboda, the Austro-Hungarian Consul at Baghdad, and Euphémie Muradjian. It was from them that he inherited his curiosity and sense taste of adventure. His father, the son of a Croat Hussar, was a dealer in crystals and cuneiform relics; his mother, the daughter of Baron d’Ohsson, was the niece of the famed orientalist, Ignatius Mouradgea d’Ohsson.

The men explored the famed hot springs, where a number of Roman columns and fragmented marble could be seen at the bottom of the water. They climbed the slope of a hill to reach the Theatre—a pursuit that was more difficult on the way back down. Barth, losing his footing on the a large stone building at the foot of the hill, was assisted by Svoboda. To the left of the building, under its walls, they found deep hole hidden by shrubs.

Stella Antonia Romanini

Svoboda looked out into the great distance at the hill range that the natives called Pambouk Kalesi, the “Castle of Cotton,” and remembered a time long ago. In 1848 he fell in love with Stella Antonia Romanini. Her father, Count Angelo Romanini, did not tolerate this love affair, and locked her away in her room. Stella escaped by climbing up the wide chimney of the house, while her sisters helped her to drag up her boxes with a rope. Svoboda, waiting on the other side, helped her down into the street when she emerged. The couple eloped and had two daughters, Effie and Joanna. Fighting back the memory, Svoboda pulled out a dog-eared copy of Strabo’s Geography from his satchel. When he located the desired page, he re-read the following passage:

Near the Messogis, opposite Laodicea, is Hierapolis, where are hot springs and the Plutonium, both of which have some singular properties. The water of the springs is so easily consolidated and changed to stone, that if it is conducted through watercourses, dams are formed consisting of one solid block. The Plutonium, situated beneath a small brow of the overhanging mountain, is an opening of only sufficient size to admit a man, but is of great depth. Round this is a square fence, about half a plethrum in circumference (50 feet.) This space is filled with a thick and dark vapour, so dense that the ground is scarcely visible. To those who approach the outside of the railing, the air is innocuous for in calm weather it is free from the vapour which then remains within the enclosure. But animals which enter within the railing die instantly. Even bulls, when brought within it, fall down and are taken out dead. We have ourselves thrown in sparrows, which immediately fell down lifeless. The Galli, who are eunuchs, enter the enclosure with impunity, approach even the opening or mouth, bend down over it, and descend into it to a certain depth, holding in their breath meanwhile, for we perceived by their countenance signs of some suffocating feeling. This exemption may be common to all eunuchs, or it may be confined to the eunuchs employed about the Temple, or it may be the effect of Divine care, as is probable in the case of persons inspired by the Deity; or it may perhaps be procured by those who are in possession of certain antidotes.

“The Plutonium is probably somewhere near this spot,” said Svoboda.

It would be quite the discovery. Ploutonions, or “Pluto’s Gates,” were religious sites dedicated to the god Pluto. Herodotus and Strabo regarded them as the Gates of Hades. The lost Ploutonion at Hierapolis was considered by many to be merely a myth.

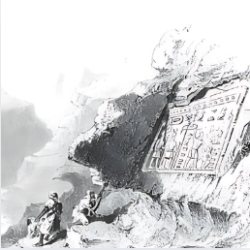

Svoboda’s Photograph of the Ploutonion at Hierapolis

“Look there!” said Barth, pointing at a dead bird between the stones near the opening.

“The bird must have come to roost, and died on the spot by the effects of the exhaled vapor from that hole.” Svoboda, wincing slightly at another slight memory, approached the rocky aperture for a closer look. Peering inside, he found that it was ten feet deep, and at the bottom there was bubbling water, and sulphuric smelling vapor. “Go to Pamukkale and procure two fowls,” Svoboda told his guards. When the guards returned with the birds, Svoboda tied a string to their feet, and directed them into the opening. They both died immediately upon reaching a level of only two feet. He then lowered a bottle into the sulphuric spring, to collect a sample for Professor Frankland at the Royal College of Chemistry.

Alexander Svoboda

Svoboda catalogued his findings, and cleaned up the camp as the sun began to set. His eyes lingered on the dead birds on the strings. Svoboda was a jealous man. His marriage with Stella was not a happy one. She had a bird which she used to feed from her lips. Even this invoked his jealousy. Svoboda killed the bird before her eyes. He could not apologize, even if he wanted to. Stella died in 1865 at the age of 29, but the couple divorced a fews years before that. Svoboda remarried in 1863 and had a new family now. In the months following Stella’s death, Svoboda made preparations to photograph the the seven churches which John of Patmos mentioned in Revelation 1:11. While he did not record what he found in the explorations of his internal ruins, his photographs and findings in Turkey were published in the 1869 book, The Seven Churches of Asia. Recognized by the academic community in his time for discovering the Ploutonion at Hierapolis, his contribution seems to have been forgotten in the century that followed.

SOURCES:

“Art And Literary Gossip.” The Manchester Weekly Times and Examiner. (Manchester, England) May 17, 1879.

Clarke, Hyde. “On The Assyro-Pseudo-Sesostris.” The Journal of the American Oriental Society. Vol. VIII. (1866): 380-381.

Hannoosh, Michèle. “The Art of Wandering: Alexander Svoboda and Photography in the Nineteenth-Century Mediterranean. Chapter in The Mobility of People and Things in the Early Modern Mediterranean. Edited by Elisabeth A. Fraser. Routledge. Oxfordshire, England. (2020.)

Mrs. Patrick Campbell (Beatrice Rose Stella Tanner.) My Life And Some Letters. Dodd, Mead And Company. New York, New York. (1922): 7.

Svoboda, Alexander. The Seven Churches of Asia. Sampson Low, Son, And Marston. London, England. (1869): 29-33, 37.

~

For more information about the Svoboda family check out The Svoboda Diaries Project.