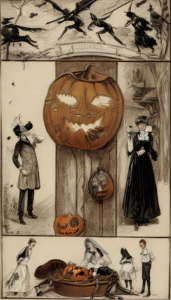

HALLOWEEN

In “olden times” it was believed that the night marked the annual return of spirits, and the occasion was one of fasting and prayer. By the turn of the (19th) century, it was already lamented that “Halloween became desecrated by the small boy, inasmuch as he considers it a night on which he can give free vent to his mischievous spirit.” The boys of New York had a variety of irritating pranks which they will make free use of tonight. One of the common ones was to walk up behind a particularly well-dressed man and strike him between the shoulders with a thin stocking full of flour. Another popular form of amusement with the boys was to travel in bands armed with potatoes and cabbage stalks and pelting a promising front door with their ammunition and make a run for it. Ringing doorbells, playing tick-tack on windowpanes, dumping ash barrels, and removing gates and signs, it was said, “[was] horseplay with which all men who have ever been real boys [were] thoroughly familiar.” The Old-World traditions survived in the New-World, however, taking on new forms and adapting when needed. Apples, nuts, rings, saucers, candles, tubs of water, turnip bogles and kale (or cabbage) were the most essential of the paraphernalia needed for a proper observance of the rites of Halloween.

KALE-PULL

Pulling the kale stocks (in some places cabbage) was a popular Halloween sport. After it was “good and dark,” young people set out (sometimes alone, sometimes in twos and threes,) to pull up the kale (or cabbages) by the roots. This had to be accomplished blind-folded and undetected. (Boys pulled them from old maid’s gardens, girls from those of bachelors, adults from a widow’s patch.)

If one’s presence was discovered, the owner of the garden had a time-honored right to “give the trespasser a good docking.” The shape and condition of the stock (or root) was said to tell a mystical tale. If the stock was misshaped and crooked so, too, would be one’s future spouse. If much earth came up with it, money would come with the marriage. Everyone took home their stock and laid it behind the outer door of their home. The first person to enter next morning was to be their future wife or husband. If the first person who entered was already married, the first letter of their name was to be the initial letter of the name of the future spouse.

TURNIP BOGLE.

The “turnip bogle” was fashioned from the biggest turnip the autumnal harvest produced. (The pumpkin took the place of the turnip in the United States.) It was often saved for the weeks leading up to Halloween. The interior was carefully hollowed out until nothing, but the shell remained. One side of it was then punctured with holes for the month, eyes and nose and made (as nearly as possible) to resemble a human face. Eyebrows were then put on it with soot to give it a demon-like expression. Horns were sometimes stuck on it to make the bogle look like the Devil (whose Sabbath All-Halloween is.) A lighted candle was then fastened within, and bogle was placed in a dark room, where the “young people may stray on it unawares,” or flashed from a window to surprise startled merrymakers.

SOLDER

Halloween was a night for divination. People would melt a bar of solder bit by bit in an iron spoon and drip it a little at a time into a tumbler of cold water. “Babies, coffins, bridal wreaths” were expected to show themselves in due order.

APPLES

Ducking for apples or pieces of silver in a large washtub was the most popular of the indoor amusements. (It was no common feat to pick a ten-cent piece from the bottom of a tub of water with one’s teeth.) After an apple was “captured,” the proper thing to do was to pare it round without breaking the skin, and after it was peeled, throw the paring over one’s right shoulder. Whatever resemblance of a letter the peel formed when it dropped on the ground was said to be the initial of one’s future husband of wife.

A stick about two feet long, tied exactly in the middle with a string, was hung from the ceiling to a level even with a person’s head. At one end of the stick was fastened a lighted candle and on the other end an apple. One after another would try to bite the apple (but typically only succeeded in “catching the spattering candle in the month.”

Other variations were had the boys stand in front of apples hung by long strings in an open door (one apple for each young man.) The one who ate his apple first with his hand tied behind his back would be the first to marry.

ENGAGEMENT

There was a time when Halloween was regarded as the luckiest night of the year to propose marriage. It was said that the couples who became engaged that night “would have the saints to protect them and give them long life, happiness and healthy children ad libitum.” Many rituals connected with this involved food.

NUTCRACK NIGHT

Nuts were so thoroughly associated with the festivities, and among those from the North of England it was called Nutcrack Night. Young couples would place two nuts side by side in the embers at the edge of the fireplace. If they burned quietly away together, they foretold a happy married life. If one cracked and jumped away it indicated a lack of harmony and an unhappy union. Another of the tests of the “Fates” was burning chestnuts that were named and placed upon a long-handled shovel in the fire. As they “burned brightly, burned black, or bursted with a loud report” good fortune, misfortune, or death was indicated.

SALT AND WATER

Girls would run around a city block with a handful of salt and a mouthful of water, and if they run clear around still holding water and salt and hear a man’s name that would be the name of their future husband.

COLCANNON

Another popular ways of forecasting the future was for the young people to place a thimble, a sixpence, and a ring into a pot of mashed potatoes (or a kettle of porridge.) Each boy and girl got a spoon and began to eagerly eat its contents. The one who got the ring was to be married within a year. The one who found the sixpence brought luck, and the one with the thimble become an old bachelor or maid. Some “canny lassies” were known to get the ring in one of their very first spoonfuls, and kept it hidden in their mouths until the kettle was emptied. “Such a lass was believed to possess the rare accomplishment of being able to hold her tongue.”

In the homes of the Irish there was a feast of colcannon (mashed potatoes,) oaten bread, potato cake, soda bread, apples nuts, and whiskey punch. A gold ring was placed inside the colcannon, and the lucky discoverer of said ring was entitled to select from the company a husband or wife, who, regardless of suitability, was compelled to submit.

THREE PLATES

One custom was to be blind-folded and then pick one of three plates containing earth, water, and a ring. Should “Fate” direct one’s hand to the first it meant death within the year; the second represented exile (or travel,) and the third meant marriage.

Another variation has a boy blind-folded and led one by one to stick their fingers in one of three bowls. If a man stuck his finger in the bowl which was empty, he would never marry. If he sticks it in one which holds clear water, he would marry. If he sticks it in one which is filled with dirty water: “Alas! the shout arises ‘a widow!”

CAKE

Some families ate a big cake at dinner time, inside which was a ring. Whichever one of the marriage-eligible youths got the slice with the ring could “rest assured that before next Halloween” they would be married.

Girls would bake a nice cake on the afternoon of Halloween. At precisely 9 p.m. she would cut it seven times, taking the smallest slice, and setting it aside. She would then eat the other six slices (the cake could be as small as one wished.) Before she went to sleep at night, she would place the smallest slice of cake under her pillow. It was said that she would have a dream of her future husband.

PAPER LADDERS.

Other bedtime rituals involved less baking. It was said that the last thing the girls usually did was cut out a paper ladder and set it at the foot of her bed that the spirit lover may run up and peep at her over the foot-board. She would then eat a thimble full of salt, hang her clothes inside out over a chair, and go to bed backwards.

MIRROR

Mirrors had a special place in Halloween observance. At midnight, when the “spirits of the dead and the wraiths of the living” were said to begin their revelry and “dare incredible exploits,” brave girls would muster their courage and light a candle from the one already lighted by “Dame Halloween” (the patroness of the festival.) She was then bidden enter a room where someone in “elfish” dress appeared “to guide her to her fate.” Without a word, and bearing her candle aloft, the girls would traverse “upstairs and downstairs, through dark halls and moldy corridors,” until her mysterious guide finally opened the door of a pitch-dark room and motioned her inside. The door was closed, and her guide would flee. Once inside the girl would find bare walls and floor, the only article of furniture being a chest of drawers, an heirloom from the time of her great-grandfather. Over it hung a cobwebbed mirror. In one of the drawers there was a box with her number on it, which she would take out and carry downstairs with her. As she approached the mirror, she would see in it the outlines of a strange face. It might be her own, or it might be that of her betrothed-to-be. If she had faith to look steadfastly, she was said to see him plainly. If she saw a “strange white face, with closed eyelids and two candles by it, instead of one,” then it was said that she saw her own wraith, the harbinger of her death within a year. As she turned to walk out again, a mysterious shadow (surely not her own!) would fall on the floor by her side. It was that of her unseen lover who walked to the door by her side.

Toned down variations saw girls walking down cellar stairs holding a candle in one hand and a mirror in the other while she invoked “the candlelight and the mirror bright” to show her future husband.[1]

[1] “All-Hallowe’en Frolicking—Oct. 31.” The Evening World. (New York, New York) October 28, 1887; “Halloween.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. (Brooklyn, New York) October 31, 1888; “Nut-Crack Night.” The Rutland Daily Herald. (Rutland, Vermont) October 31, 1889; “A Night Of Omens.” The Evening World. (New York, New York) October 31, 1889; “All Halloween’s Delight.” The Evening World. (New York, New York) October 31, 1890; Wilkes, John. “Historic Hallowe’en.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) October 28, 1906.