THE DAGHEE

Charles Johnston

Mid-February 1889.

Who would have thought there was a woman in the case?

“Who is he, Babu?”

The old man was squatting on the ground behind his tile, looking up at us with a glint of fire in his eyes. He was not like the rest of our tame Bengali jail-birds. Not only was his face different—wide cheekbones, olive skin, eyes a bit oblique—but there was a vigorous, breezy air about him: big mountains and forests and precipices in the background. Not one of our flat-footed Delta folk.

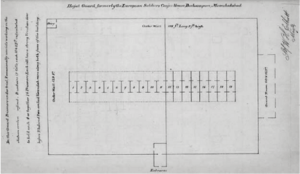

Plan for Berhampore Jail.[1]

“This fellow, sir?” responded the fat-bellied jail superintendent, Babu Hari Kishto Mozumdar, in his fluttering white garments. “Yes, sir! He is a Burmese!—a prisoner from Burma, sir!” and the Babu gave a wave of his plump brown hand, indicating far-off barbarian strands: “He is a daghee!”[2]

“What is a daghee, Babu?”

The Babu colored with pride and pleasure under his brown skin. He loves to instruct the white person.

“A convict, sir! A life-convict!—It comes, I believe, sir, from the Perzyan—that is how Hari Kishto Babu pronounces Persian—“the Perzyan, dagh, a wound.[3] Our predecessors used to brand them, sir!” (By “our predecessors” the Babu meant the Moguls.)

The old Burman’s eyes leaped from my face to the Babu’s. He was getting a bit restive, though he sat very still, rather like a frog on a water-lily pad.

“What is his name, Babu?”

“We call him Manmathan, sir!”— Again the patronizing wave of the hand. Instantly the old fellow was on his feet, with a vigor that made the Babu jump back and turn gray.

“Sahib! My name is Maung Hkin!”

“The foreign name is difficult for us,” the Babu palliated. “Therefore we have adapted it, speaking of him as Manmathan.”

“Maung Hkin! My name is Maung Hkin!”

“Maun Kin!” the Babu attempted, cowed.

“Muang Hkin!” I tried to follow the sounds exactly. The old man was mollified and smiled.

“They would take even my name,” he said in his deep voice, glaring at Hari Kishto. “These Bengali—”

I hastened to interrupt. “A good name! A very good name! What is its significance, Maung Hkin?” And I laid my hand on the old man’s shoulder.

He seemed rather to like it and smiled again.

“I was born,” he said, “at Magwe, on the Great River, on the day of the moon! Therefore I am called Maung Hkin—’He who awakens love.’”

I looked at the old man—sallow, white-haired, wrinkled, withered, a mat of grizzled hair on his breast. “He who awakens love!” Then an etymology flashed into my mind.

“Babu! What is the meaning of Manmathan?”

“It is an epithet, sir, of the God of Love,” and the Babu rolled his eyes; “of Kandarpa, ‘Whose bow is of flowers, with honey-bees composing the string.’ The name signifies ‘the one who pounds the heart.’” He laid his plump paw just above his stomach, as if he too had suffered wounds.

“There!” I said to the old man. He was by this time considerably pacified. Perhaps the Babu’s poetry did it. “Manmathan is exactly the same as Maung Hkin! One is Sanskrit—the other is Burmese.”

“Sanskrit, Sahib? Not Bengali?” he asked a bit querulously.

“Pure Sanskrit! Kalidasa, isn’t it, Babu?”[4]

The Babu beamed and showed his white teeth. Everyone likes his quotation recognized.

“Well,” the old fellow accepted it; “if Manmathan is the god of love—”

And with that he sat down on his heels again behind the square tile.

“A fiery old person!” Hari Kishto Babu commented; “a highly irascible old person!”

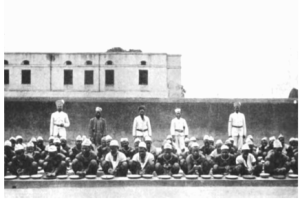

We left the old Burman and went on down the line. We had a hundred of them, in four rows, squatting in the shadow of two immense peepul trees, a flat tile nines inches square topping a little mound of earth in front of each of them. That is our jail provision for dinner tables. On each tile, two large flat leaves were laid, by way of dishes.

Presently the two cooks emerged from the cook-house, and came toward us, blinking, through the glare of sunshine. To each man the cooks, who also were prisoners, doled out, from big earthen pans, first a little hill of well-cooked rice, then a heap of curried vegetables and fish.

“Who are your cooks, Babu?”

“They are Kshatriya, sir—men of the Warrior-caste—in jail for felonious assault, sir! Before them, we had Brahman cooks—much higher caste—but they were released last month”

Yes! In this heathen land dinner is a rite, even in jail, which only a high-caste man is fitted to administer. I rather fancy the notion.

Behind us, a stir and raised voices. Two or three of the men rose to their feet. Others simply revolved gleaming dark eyes toward the noise.

I turned quickly on my heel. Our rugged old friend Maung Hkin was the center of it, drawn to his full gaunt height, wildly brandishing his fist in the face of one of the cooks, who, for a man of the Warrior-caste, looked rather abashed. The Superintendent Babu and I hurried over to them and I am convinced, just saved the Warrior-cook from getting his head punched.

To the Babu’s evident displeasure, I laid my hand on the old man’s shoulder. He started and wheeled quick round on his bare heels. His fiery eyes met mine; when I smiled, he suddenly quieted down and looked deeply ashamed, blushing a kind of olive brown.

“What is the matter, Maung Hkin?” I asked.

“This Bengali ” he said, flaring up again.

I cut him off. “Yes, I know! What has the Bengali done?”

“He has stolen my mutton!”

The old man’s face was dark with indignation. Hard put to it not to burst out laughing, I turned to the Babu.

“This man is a Buddhist, your honor,” he explained, with a slight Brahmanical sneer, “and he eats sheep. It is prepared for him each day.—Where is his sheep?”[5] He turned haughtily upon the brow-beaten cook.

“His sheep is in the kitchen. I cannot serve it! It is against my caste!” the Warrior-cook explained.

“Who usually serves it?” I asked.

“We had a Mohammedan boy, Khoda Baksh!” the Babu explained. “But he is in hospital. He is sick your honor.”

“Come, Maung Hkin! Come, Babu!” I found a solution. “We shall get it from the kitchen ourselves!”

Mealtime in a Bengal Jail.[6]

We crossed the glaring sunlight, plunged into the redolent darkness of the brick cook-house, and found the mutton stewing in a little earthen pot over charcoal. Maung Hkin stooped to lift it, burned his fingers on the rim of the pot, and laughed happily—until he saw the Babu laughing. Then he laid the little pot down and rushed at the Babu, who precipitately fled.

I grabbed the Burman by the arm; his withered body swung against me. He was trembling with wrath.

“Bengali pig! Bengali pig!” he panted, his eyes on fire.

I held him tight, remonstrating. “Maung Hkin! Maung Hkin! You would hit a Bengali?”

It was as if I had accused him of maltreating a child.

He was quieting down, when Hari Kishto Babu came striding back with two up-country warders armed with batons.[7] At the door, he stepped behind them, pushing them in first. Had I not been there, unpleasantness would have supervened. There was one quick way out of it.

“Babu,” I said, magisterially, “I have ordered Maung Hkin to solitary confinement for insubordination! Get the keys of the cells!” Charley said, magisterially. “Maung Hkin, bring your mutton and come!”

The old Burmese followed trustingly, while the Babu bustled off for the keys, his white garb fluttering, in heart exultant over his enemy—of whom, to tell the truth, he was horribly afraid.

I took the bunch of big, well-oiled keys, opened the cell-door myself, to soften it to the old man, signed to him to go in—and then had an idea.

“Babu,” I said, “I shall see to this man! Go to the office and get the accounts ready for me! I shall go over them minutely!”

The Babu went off haltingly, with an uneasy mind. He is quite honest, Hari Kishto Babu, but he has a haunting fear of what might happen if someday the accounts should not come out.

There was a low bench at the back of cell, which was a quiet, cool little like chamber, like a garden-house, well-fitted for meditation. I bade Maung Hkin sit down on the bench, followed into the cell, and pulled the door, leaving a space of six inches. I watched him eat his mutton, daintily, his lean finger-tips, which he then carefully polished on his one garment—rather like blue bathing-trunks, with white stripes. Then I sat down beside on the bench, and pulled out a cigarette case. Maung Hkin’s eyes sparkled as he watched me, but he said nothing. In cells, smoking is strictly forbidden. I lit a cigarette, drew in the scented smoke, and puffed it out in a cloud in his direction. He sniffed up gleefully with his big round nostrils, murmuring, “Ah!”

I met his eyes—fine, honest old eyes they were—smiled, laid a hand his bony knee, and handed him the cigarette, saying, “It is permitted!”

He smoked it long and lovingly, in haling and holding the smoke in his lungs, then letting it filter out through his nostrils.

Finally I said, “Maung Hkin, tell the story of your coming here!”

At first, he hesitated, looking down, his cheeks dull brown. I laid my hand on his.

“That is why,” I said, “I have brought you here—away from the Bengalis.”

“Yes, Sahib! A light people, like the fluff of the silk-cotton tree!—Or like the Bunder monkeys in the jungle.”

“Or like the peacock that cries before the rain?” I suggested.

The old man chuckled, delighted, as he puffed at my cigarette. Then he fell into reverie, seeing things far off and long ago. I was careful to keep silent. At last he began to speak, and his voice came over the spaces of the years.[8]

“It was on account of her, my beloved, that I was brought here!—Ma San Nyun, her name was; born like me on the day of the moon; therefore the moon-god drew our hearts together![9] She was very fair, and small, and merry—very lovely to the eyes. And I think that, in the beginning, her heart was mine. For I was a fine young fellow in those days, Sahib, worth any girl’s eye, and I had boats upon the great river, in the grain-trade, and all things prospered with me! And I loved her and had it in my heart, when the young moon that drew us should come again, to persuade her, and carry her off with me to the forest. But one of your own people, Sahib, a masterful man and cunning, came between us.[10] He was hunting elephants in our mountains, and he stayed three days at Ma San Nyun’s village. When he departed, she was gone also; and never since then have I set eyes on her or heard of her.

“My heart was full of thorns and fire. I left my boats there on the river, with the grain in them, to rot, and took to the jungle. We were fifty men, well-armed, with good flint guns, and we made the villages along the Great River and through the hills pay tribute to us, or, if they would not, we fought them for it![11] And, Sahib, in the rush of the fight, when bullets were singing about our ears and men were shouting to each other through the smoke burning huts, I forgot the face and name of Ma San Nyun, and I had peace. But in the evening, as lay about the campfires in our hill fortress, reckoning up our spoils, her face would come back to me, small and merry and lovely, her eyes like stars, and then the fire broke out again in my heart, and gnawed me like a leopard. Then I wandered out into the night, moaning to myself, and all the time her face was before me, beckoning to me.

“Just before the red of the dawn she led me to her village; and it came to me, as I lay there looking through the undergrowth, that, if I burned the village, her face would leave me, and I would have rest in my heart. It was the dry season then, at the end of the month of flowers. So I made fire—I had my gun with me—and ran from house to house in the gray of the dawn, setting the red torch to the thatch and the palm-leaf matting of the walls; and as the smoke surged up into the sky, the dogs began to bark, and the whole village broke forth in an uproar, with shrieking and cries, and it brought great quietude to my heart. I could have fled then, to the river, and escaped, going back to our band, but the fire held me. It was burning the pain out of my heart! So I crouched there behind a tree, watching the red tongues licking along the eaves of the thatch, when the dogs found me, and came howling about me. The watchmen ran to the sound. One I shot, and wounded another, hitting him with the butt of my gun—I was a good man, in those days, Sahib!—and would have done for more of them, but a stray bullet caught me, and I fell. But my heart was cooled and solaced by the flames. As the houses burned down to ashes and blackness, so did my pain burn out; and as the village was gone, leaving bare jungle, so her face was burned from my heart, leaving peace. Then I knew I had done well.

“These Bengalis would not know how killing solaces a man; but, Sahib, you understand! And then they carried me away in chains, and I was sent hither, but there was laughter in my heart! And here they love me, as one who has fought well, for many times I have told the tale. But of her, of Ma San Nyun, I have not spoken—never until today! Now the Sahib must go, for it is not seemly for the Sahib to remain here with an old daghee like Muang Hkin. Do not fear, Sahib! I will do no violence to the Babu! I will sleep and dream.”[12]

“Very well, Maung Hkin,“ I replied, as I rose and patted him on the shoulder. “When the sun sets, I’ll return and open the door. In the meantime, farewell! It was a good tale; such a tale as warms the heart!”

At sunset I came back and unlocked his cell, having in the meantime harassed the blameless Babu concerning his accounts, which though irregular in shape, with some vouchers missing, were in substance accurate. Wherefore the Babu was properly subdued when he came with me for the old man, and hung a little behind me, lest the “irascible old person” might flare up again. But Maung Hkin had had a good nap, and went off quite quietly for his supper.

It must have been about nine that same evening. Punaswami fed me indifferently well on local moorghee—which is to say, chicken—with curried rice and vegetables from the bazaar.[13] The two Punaswamis were the first butler, and first valet, in my household, whom I had imported from Madras. Punaswami the elder, whose gold and crimson turbans were a joy, cooked admirably, yet he once shocked me beyond words by asking for cook-money to buy the makings of a “kerosene pudding,” averring that he had often served just that very dish to the Governor of Madras. Even had the Viceroy, or visiting royalties, feasted on kerosene, I flatly refused. Punaswami pleaded, and finally brought, to convince me, the head valet, Punaswami the second, bearing a much-thumbed Tamil-English wordbook, and pointing in triumph to the word, “Curaçao.”[14] After a comfortable dinner, I was sipping my coffee and turning over the pages of a month old London Graphic, in the cool stillness of my veranda. The crickets in the trees along the square had ceased their vesper concert, and the mosquitoes, happily, seemed to have gone elsewhere.

Something moved out under the flame-flowered acacia across the grass, and then came toward me through the gloom, emerging into the circle of lamplight as an extraordinary pillar of vivid green. It was old Maung Hkin draped in a heavy piece of green baize, that looked as if it had come straight off a billiard table. I admit I was somewhat taken aback.

“But, Maung Hkin!“ I expostulated, rising. “You have no business to be here! You ought to be in jail!”

“It is well known, Sahib. But—I had need to talk with you,” he answered with innocent earnestness.

“That’s all very well, Maung Hkin! But how did you get out?” I twitched the end of his green baize shawl. It is not the kind we furnish to our—guests.

“The Babu was going home, Sahib,” he answered gravely. “He stood at the gate!” Then a glint of humor lit his honest old eyes. “He would have delayed me. Therefore I—butted him in the stomach, and—borrowed this! After we have talked, Sahib, I shall return, taking this back to the Babu!”

“Maung Hkin, this is highly irregular. I am afraid I shall have to put you back in cells tomorrow!”

“It is well, Sahib!” The old gentleman grinned. “I have other stories of the old days! There was the raid on Bghai, and the fight for the river boats, and the meeting with the elephant herd; many stories, Sahib! But that is for tomorrow, in cells! I have another matter tonight; it cannot be said to a Bengali!”

“All right, Maung Hkin! Go ahead. I am listening!” And I made the old man sit down beside me, where I could watch the play of his fine wrinkled old face in the lamplight.

Maung Hkin’s face, sallow, wrinkled, rough-hewn, grew pensive, almost melancholy. No; that does not express it: an otherworldly light glowed in the fine old eyes, and he seemed infinitely remote from the earth.

“Sahib!” his deep voice began, after a long pause which I was careful not to break. “Sahib, the time has come for me to die! It was revealed to me this afternoon, while I slept!”

I was a bit startled. There was nothing weak or sepulchral in his tones as he brought it out in well-rounded Bengali—

“Amar morite hoibe! Shomoy achhe!”

He spoke it well, but with an outland tang.

“Nonsense, Maung Hkin!” I finally broke out; “why on earth should you die?”

“Because my time has come, Sahib. None lives beyond his appointed hour. Karma!—The Sahib knows the law.”

I saw that it was no use protesting. The old man had made up his mind—and might die of that alone. However he had come to his conviction, he was palpably convinced.[15]

“Your time has come, then, Maung Hkin?”

“Even so, Sahib! The time has come. Therefore my petition is this—let me not die here among strangers, among these Bengali—”

“Never mind the Bengalis, Maung Hkin! Your petition is—?”

“That I may return to my own land, Sahib. My heart is hungry for the hills. Let me see again the big forests, and the Great River, slipping through the heart of the forests! Let me go back to the village of Ma San Nyun, that I may see it once more, and die in peace.”

The tears gleamed in the old man’s eyes, as the bright lamp-light fell on his face. He was too proud, or too unconscious, to wipe them away; but when he laid his hand on mine, it was trembling.

Well, a Deputy Magistrate of the Second Class cannot say to a life-convict, “Go home to your own village, and die in peace!” however much might like to say it. I tried to explain that to Maung Hkin with the reasons of it; but he persisted in his prayer and his belief. He was so firmly convinced that I finally gave him a half-promise to see what could be done. He was so happy over this that in his gratitude he told me a vigorous tale of his old band, and how, on a raid, they had spitted a fat headman with boar spears; then, after we had sat a while in the darkness, lit only by the circle of the lamp, I bade him good night and escorted him back under the stars to the gate of the prison. We made up a story to mollify the Babu, who was really very offended about being butted in the stomach, and we gave him back his green baize shawl, of which he is prouder than if it were the finest Cashmere. Only, I think he wishes it was scarlet. Both are fashionable now.

On the next day, with some natural hesitation, I took Maung Hkin’s matter up with Tuite-Dalton. At first the Collector Sahib was astonished. Then he began to laugh. Finally, he said—“Oh, I remember the old chap. Nice old person! So he thinks he is going to die? Looked hale and hearty when I saw him.”

I pressed my plea. The old man was perfectly harmless. He had done twenty or thirty years. Perhaps there was really something in premonitions. And this Delta country was appallingly flat for a hillman! Well the upshot was that Tuite-Dalton allowed himself to be talked over, and we made up the most persuasive memorandum to Sir Steuart Bayley, the Lieutenant-Governor, in fact urging him to let a murderous old person loose on society.[16]

In a week or two we received an answer. “In consideration” and so forth and so forth, Maung Hkin might go free. It being understood, though not baldly expressed, that he must go home to his village and die.[17]

That was just what he wished to do. There was a moving scene of leave-taking in the jail-yard, for he was called “the father of the prisoners,” and he had spoken the truth when he said they all loved him—in part, I think, because he kept Hari Kishto Babu in bodily fear. But the Babu parted from him without regret.

I drove him over to the junction and bought him an intermediate ticket to Calcutta—which was extravagant, also giving him directions to take the steamer thence to Rangoon, and up the Great River among the hills. Poor old chap, I thought, as I drove back through the dust and the sunshine from the junction, there was no “Burma girl a-waiting” in his case![18]

The old man haunted my thoughts a while. Then, with the stress of small criminal cases and excise matters, and with the hot weather coming on, I am afraid he dropped into the background and got forgotten.[19]

← Table Of Contents →

SOURCES

[1] Waits, Mira Rai. “Imperial Vision, Colonial Prisons: British Jails in Bengal, 1823–73.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. Vol. LXXVII, No. 2 (June, 2018): 146–67.

[2] The Administration Report Of The Jails Of Bengal For The Year 1889 stated: “There were 404 Burman convicts in jail on the 31st December 1888, and 200 were admitted during the year under review, bringing the total to 604. Their conduct in jail has been on the whole good, and, notwithstanding the large increase in their numbers, the offences recorded against them during the year only increased from 434 to 455, of which 271 related to work. One of the convicts was sentenced to capital punishment for having murdered another Burmese prisoner, a convict overseer, and there was another co^ of serious assault, in which a Burman attacked a Bengali prisoner, but the measures immediately taken prevented him from doing much harm. The Burmese are a dangerous class of prisoners on account of their instability of character, their impulsive nature, and their great impatience of restraint, but their capacity for work is superior to that of other native convicts, and the Superintendents are naturally inclined to appoint them freely to jail offices. It is not, however, safe to have a large proportion of these men as overseers and convict warders, for even holding offices of trust is not sufficient to restrain their longing for freedom. The Jail Committee have therefore proposed the introduction of a ticket-of -leave system for them, a measure which has been advocated by this* Government for the last three years. The question is now under the consideration of the Government of India.” [Lethbridge, A. S. Administration Report Of The Jails Of Bengal For The Year 1889. The Bengal Secretariat Press. Calcutta, India. (1890): [Resolution: Jails. Dated Darjeeling, the 18th June 1890]: 2.]

[3] Daghee, v., meaning “damaged,” “to blemish,” or “to brand.” [Gilchrist, John Borthwick. Hindoostanee Philology. Kingsbury, Parbury, And Allen. London, England. (1825): 58, 67, 145.]

[4] Johnston writes: “It has often seemed to me that even the best Sanskrit scholars in Europe and America alike have no very clear insight into the purpose and tendency of their work; and I know more than one, among those who hold high rank as unquestioned authorities, who candidly admits an entire ignorance of the use of Sanskrit studies,—supposing them to have any use. And there is, I think, a very obvious reason for this dim and uncertain attitude; for, even though it may sound somewhat venturesome to say, so, it seems that, for the most part, our Sanskrit scholars study the wrong things, or, if they find themselves, by accident, among the right things, they study them in the wrong way. If we look at the history of Sanskrit studies during the past century, we shall probably be able to find the reason of this. To begin with, the first generation of Orientalists, setting to work in Lower Bengal, naturally came to study the works most familiar to the Bengal pundits—the artificial, or at least too ornate, poetry of Kalidasa; and the law-books, with Manu’s Code at their head. Now, no one who has read Kalidasa’s best verse can deny its possession of a very perfect and delicate beauty, gorgeously vivid coloring, great subtlety, and refinement of fancy, and rich and ever varying music, which makes up in skillful modulation what it lacks in spontaneous freshness. Of our European poets, Kalidasa comes closest, perhaps, to Theocritus and Petrach; and much that is characteristic of his style is very marked in the verse of Rossetti and Swinburne. Yet we need no prophet to tell us that the treasure of the East is not with Kalidasa—for all his enameled beauty; and as little would we expect to find the justification of our studies in the wonderfully elaborate polity of Manu’s Code. If that were all India had to offer, it is doubtful whether Sanskrit could claim an intellectual position much higher than that of Syrian or Ethiopian—both of which contain much to interest specialists; something of more general interest, but almost nothing of universal value.” [Johnston, Charles. “The Culture-Language Of The Future.” The Theosophist. Vol. XIX., No. 3. (December, 1897): 146-148.]

[5] As was the case with other Bengal jails with Burmese prisoners, such as Shahabad, Moffuzerpore, and Monghyr, Maung Hkin was allotted a certain portion of meat in lieu of dal. [Lethbridge, A. S. Administration Report Of The Jails Of Bengal For The Year 1889. The Bengal Secretariat Press. Calcutta, India. (1890): [Judicial Statement No. IX]: xliii-xliv.]

[6] Bradley Bradley-Birt, Francis. The Romance Of An Eastern Capital. Smith, Elder, & Co. London, England. (1906): 246.

[7] These men, like the prison cooks, were also prisoners. Inmates who displayed good conduct were selected as prison guards, of which there were three grades. The third, and highest grade, was convict warder who functioned, for all intents and purposes, as a regular paid warders and given handsome uniforms. [“By-Paths Of Crime In Calcutta: I. The Jail Birds.” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (Calcutta, India) July 6, 1889.]

[8] Johnston, Charles. “The Reincarnation Of Maung Hkin.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXVI, No. 5. (November 1915): 616-624.

[9] The names given to Burmese girls were an indication as to their character. The name was selected from a certain arrangement of consonants used for people born on particular days, and therefore presented a certain limitation to the names. The first part of Ma Sun Nyun’s names, “Ma,” means something like the English word, “Miss.” San means “moon.” [Fraser, John Foster. “The Burmese Girl.” The Lady’s Realm. Vol. V. No. 2 (December 1898): 211-217.]

[10] W.W. Hunter observed that the Karenni were a tribe “whose traditions have a singularly Jewish tinge.” With traditions analogous to the Fall, the Flood, the dispersion of nations, and the origin of the differences in language, some contemporary scholars were of the opinion that [Karenni] were descended from the lost tribes of Israel. [Merriam, E.F. “The Karens.” Ford’s Christian Repository & Home Circle. Vol. XL, No. 2. (August, 1885): 147-149; Anon. “Something About The Karens.” All The Year Round. Vol. XLIII, No. 1045. (December 8, 1888): 536-542.] The American missionary, Dr. Francis Mason, went so far as to suggest that these Karenni customs might be “relics of some primeval and universal revelation, granted to all nations, which is supposed by many to have preceded the later and special revelation,” noting that the Karenni had a prophecy to the effect “that at some future day ‘white foreigners’ would appear amongst them, and teach them the true religion.” [Fytche, Albert. Burma Past And Present: Vol. I. C. Kegan Paul & Co. London, England. (1878): 169.] This, perhaps, might explain the reasoning behind Ma San Nyun’s receptivity to “sahib” visitor. There was, however, an old Karenni proverb of which Maung Hkin would have been aware: “He that awakens a sleeping tiger, the girl that loves the white man, and he that sleeps in Bonnee Forest, will come to grief, and be ruined for life.” [Anon. “Dietrich Brandis.” The Indian Forrester. Vol. X., No. 8. (August 1884): 343-357.]

[11] In the mid 1850s, just before the Sepoy Mutiny, the imperial dreams of British expansion in the sub-continent were checked by “primitive” hill peoples. [Fytche, Albert. Burma Past And Present: Vol. I. C. Kegan Paul & Co. London, England. (1878): 165.] In Burma the British, who occupied the province of Pegu, found their efforts hampered on the Toungoo frontier by the Karenni, a people “declared to be so wild, and so untamable, that the authorities [the British] supplanted were only able to exact nominal tribute at irregular intervals, and never ventured into the country occupied by them excepting in armed force.” They lived up to their reputation for “turbulent and undisciplined behavior,” and their defiance toward the British won them a “unique and independent position.” [MacMahon, A.R. “Karenni And The Red Karens.” The Asian Quarterly Review. Vol. VIII, No. 1. (July, 1889): 144-167]; During this period, a messianic Kaya emerged named Ming Luong, who led a small band of rebels, and gave “considerable trouble to the English authorities.” Ming Luong proclaimed himself the incarnation of a deity, and it was his mission to drive the English out of Burma and establish a Karenni dynasty in Pegu. Maung Hkin, like several other desperate men, placed his implicit faith in the divine mission of this mysterious leader, and joined the rebellion. From their base, hidden in a large cave, thirteen miles from Shoay Gyeen, between three immense ranges of hills which “defied the engineering skill of the British,” these rebels launched their raids in the jungles of Burma. [“The Rebel Leader Min Loung.” The Dublin Daily Express. (Dublin, Ireland) April 15, 1857; Fytche, Albert. Burma Past And Present: Vol. I. C. Kegan Paul & Co. London, England. (1878): 170-171.]

[12] The Karenni believed that all objects, animate and inanimate alike, had a presiding spirit, or kelah, whose presence was necessary for their existence. The kelah resided on the back of one’s neck, and wandered forth at night during sleep. The Karenni placed a premium on their dreams, for it was believed that they were a record of what the kelah witnessed its wanderings. [Mason, Francis. Burmah, Its People And Natural Productions. Trübner & Co. London, England. (1860): 108; Tylor, Edward B. “The Religion Of The Savages.” The Fortnightly Review. Vol. IV. No. 31. (August 15, 1866): 71-86; Fytche, Albert. Burma Past And Present: Vol. I. C. Kegan Paul & Co. London, England. (1878): 353; Hackney, J. “The Karens Of Burma.” The Gospel In All Lands. (May, 1890): 203-207.]

[13] Johnston, Charles. “Okhoy Babu’s Adventure.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXIV, No. 3. (September 1914): 309-316.

[14] Johnston, Charles. “Helping To Govern India: Kandi Subdivision.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CIX, No. 2. (February 1912): 265-273.

[15] Johnston, no doubt, would have remembered his conversations with T. Subba Rao concerning “sushupti,” and that “deeper consciousness sometimes floods back into dreams, and makes them prophetic, visions of things to come.” [Johnston, Charles. “East And West: Helping To Govern India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CIX, No. 3 (March 1912): 324-331.]

[16] For context, Tuite-Dalton was just a few weeks shy from beginning his two-year leave of absence. [“Bengal Government Orders.” Civil & Military Gazette. (Lahore, Pakistan) February 25, 1889.]

[17] Steuart Bayley long championed a “ticket-of-leave” scheme for Burmese prisoners who served for a certain time. The responsibilities of jail officials having greatly increased since their arrival, it was now deemed more favorable to return them home then to imprison them. [Purves, H.B. Administration Report Of The Jails Of Bengal For The Year 1888. The Bengal Secretariat Press. Calcutta, India. (1889): [Part D. Miscellaneous Statements Prescribed By The Government Of India: Resolution. p. 2.]]

[18] Kipling, Rudyard. The Barrack-Room Ballads. Heinemann And Balestier. Leipzig, Germany. (1892): 57-61.

[19] Johnston, Charles. “The Reincarnation Of Maung Hkin.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXVI, No. 5. (November 1915): 616-624.