There remain many open questions. My point here isn’t so much to defend a radical read of Scripture as much as it is to give a sketch of the possibilities. We read Scripture in ways that support authoritarianism because we learned how to read Scripture in authoritarian contexts. Once you start pulling the loose threads, you begin to find the whole authoritarian fabric unraveling. For sake of brevity, I’ll address the two most commonly raised passages against Christian radicalism.

The first is Romans 13, where Paul tells his readers to “submit to the governing authorities”:

Let every person be subject to the governing authorities. For there is no authority except by God’s appointment, and the authorities that exist have been instituted by God. So the person who resists such authority resists the ordinance of God, and those who resist will incur judgment (for rulers cause no fear for good conduct but for bad). Do you desire not to fear authority? Do good and you will receive its commendation, for it is God’s servant for your good. But if you do wrong, be in fear, for it does not bear the sword in vain. It is God’s servant to administer retribution on the wrongdoer. Therefore it is necessary to be in subjection, not only because of the wrath of the authorities but also because of your conscience. For this reason you also pay taxes, for the authorities are God’s servants devoted to governing. Pay everyone what is owed: taxes to whom taxes are due, revenue to whom revenue is due, respect to whom respect is due, honor to whom honor is due.

Romans 13:1-7

When interpreting this passage, there are several things that one must keep in mind:

1) This passage occurs immediately after Romans 12, where Paul challenges his readers to bless persecutors, live peaceably, never avenge, feed enemies, and overcome evil with good. By clear implication, the “governing authorities” are persecuting enemies whose evil needs to be overcome with good. Given that Paul is likely drawing directly from Jesus’ teachings, it may be best to interpret the call to “be subject” as an application of the call to “turn the other cheek.” It is not a call to mere obedience or happy citizenship.

2) Jacques Ellul suggests “the passage thus counsels non-revolution, but in so doing, by that very fact, it also teaches the intrinsic nonlegitimacy of institutions.” In other words, the very fact that Paul has to argue, in light of enemy-love, that the people should forsake (violent) resistance reveals that the “governing authorities” are, in some sense, worthy of revolt. Just like Jesus’ call to turn the other cheek recognizes that, under normal circumstances, one would hit back. To refrain from violence is a testimony to the the Roman Christian’s goodness, not the goodness of Rome.

3) Some scholars have (rightly) challenged translating the Greek word tasso as “instituted.” Rather, they argue that a better translation would be that the authorities are “restrained” by God. Therefore, Paul could be advising his readers against revolt since God is already restraining the rulers.

4) Due to the nature of translation and the dualism in our modern imaginations (separating spiritual from political realms), we don’t often recognize that Paul’s language around the “powers” blurs the distinction between political and spiritual realities. When we read words like “authorities” or “rulers” or “powers,” Paul may be talking primarily about spiritual realities, political realities, or (most likely) both at the same time. This adds complexity to what would otherwise seem like a straight-forward challenge to be “subject” to the “authorities” because, elsewhere, such “authorities” are enemies to Christ.

5) It is a mistake to take Romans 13 as a universal message of how Christians everywhere ought to relate to government. Wes Howard-Brook states:

We can say, though, that whatever Paul meant to convey to the Christians at Rome in the 50s, it was not a general principle of subservience to imperial authority…we’ve seen how Paul’s letters regularly insist on attributing to Jesus titles and authority that his audience would certainly have heard as “plagiarized” from Roman sources…The most likely explanation of Romans 13 is that it was a message addressed to specific concerns of Roman Christians under Nero.

And so, from Paul’s perspective, the Christians in Rome in the 50s should not revolt. Rather, they should love their oppressors and leave wrath to God. This wasn’t because the Roman government was good, but because followers of Jesus are called to the way of love. Furthermore, God has restrained the authorities and will judge them.

Much more could be said about what such teachings could mean for us. At the very least, it encourages us to trust God and love our enemies. While Paul argues against violent resistance, his words leave room for nonviolent struggle. It would be foolish, I think, to extrapolate universal principles of governmental engagement from this passage. Nevertheless, once we understand Paul’s sentiments, we can better discern how to express the love of God in our own contexts.

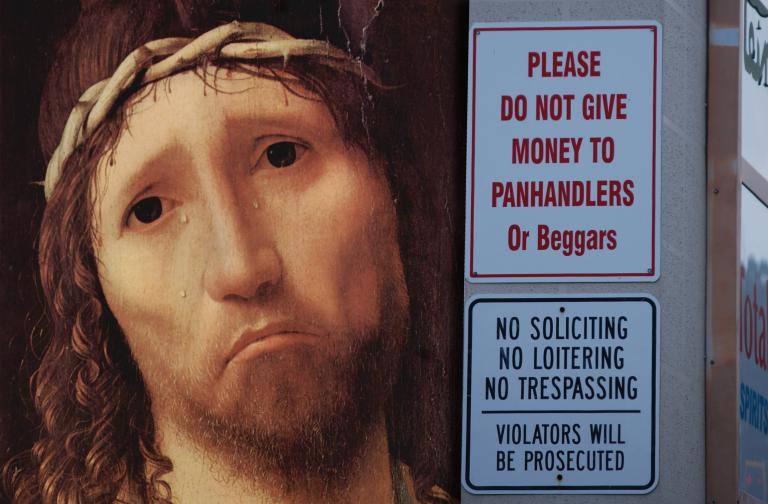

Tied for the most referenced pro-Rome passage is Mark 12:13-17:

Then they sent some of the Pharisees and Herodians to trap him with his own words. When they came they said to him, “Teacher, we know that you are truthful and do not court anyone’s favor, because you show no partiality but teach the way of God in accordance with the truth. Is it right to pay taxes to Caesar or not Should we pay or shouldn’t we?” But he saw through their hypocrisy and said to them, “Why are you testing me? Bring me a denarius and let me look at it.” So they brought one, and he said to them, “Whose image is this, and whose inscription?” They replied, “Caesar’s.” Then Jesus said to them, “Give to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” And they were utterly amazed at him.

Clearly they were trying to trick Jesus into publicly picking sides either would be dangerous. If he sided with Rome, he’d lose the support of the people. If he denounced Rome, he’d be a marked man. The fact that Herodians and Pharisees are working together against Jesus is telling; Jesus is so offensive that enemies have put aside their differences to resist him. What is remarkable about this passage isn’t so much that Jesus is clever. The implications of his statement are remarkable.

Are the implications that we should be Augustinian, creating a distinction between church and state? Or even separating them into two separate kingdoms with different claims as Luther or some Anabaptists have advocated? No. This is a very smart slap against Caesar without simply denouncing Caesar. By pointing to their coin (no good Jew should have a graven image like a coin in their pocket to begin with), Jesus is exposing idolatry and saying that such things belong to Caesar already, not God. If you’ve got any Caesar-stuff, it should be rendered accordingly. But what is God’s belongs to God. Or, to quote Dorothy Day, “If we rendered unto God all the things that belong to God, there would be nothing left for Caesar.”

Lest you think that such approaches to scripture are a recent innovation, I direct you to Irenaeus. Irenaeus was a 2nd Century bishop on the fringes of the Empire in Lugdunum, Gaul. He was a disciple of Polycarp, who was a disciple of the Apostle John. In other words, he was removed from Jesus by two generations; he was a friend of a friend of Jesus:

The Lord himself directed us to “render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s, and to God the things which are God’s,” naming Caesar as Caesar, but confessing God as God. In like manner also, that which says, “You cannot serve two masters,” he does himself interpret, saying “You cannot serve God and mammon,” acknowledging God as God, but mentioning mammon, a thing also having an existence. He does not call mammon Lord when he says, “You cannot serve two masters,” but he teaches his disciples who serve God, not to be subject to mammon nor to be ruled by it…

In other words, Irenaeus believed that the thing we should render Caesar is our renunciation. Caesar’s lordship is comparable to that of mammon 11. He is only your lord if you are his slave.