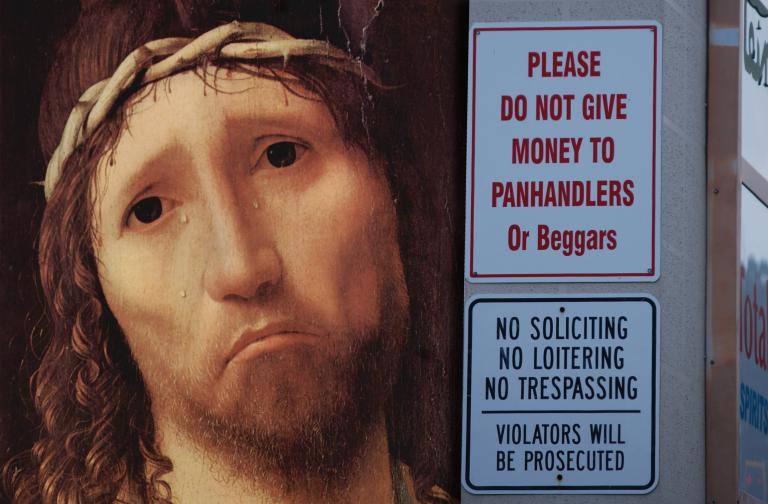

Traditional kingship (with absolute power, hoards of wealth, and power over the weak) has nothing to do with Jesus; it’s something Jesus rejected.

Traditional kings demand allegiance and servitude, but Jesus offers liberation—from suffering, sickness and death, exclusion, persecution, and sin. Jesus is a “king” who serves the “least of these” and who finally receives torture and execution to bring freedom to others.

As we see in the Gospels, Christ’s kingship is inconsistent with traditional structures of power. And for this reason, Jesus tells Pilate that “my kingdom is not from this world” (John 18:36). Passages like these have, unfortunately, fostered an ineffectual other-worldliness among Christians. And they have been used to legitimate “real-world” kingdoms. Jesus rules some magical sky-kingdom, while princes and emperors can dominate flesh and land.

But Jesus’ reign isn’t other-worldly. It isn’t apolitical. It’s just political in a radically different way. Rather than taking Caesar’s throne (or any throne—including the one Satan offered him), Jesus is saying that Caesar’s days are numbered. By saying “my kingdom is not from this world” he isn’t saying “my kingdom is only spiritual, so you don’t have to worry.”

Jesus’ kingship renders Caesar’s obsolete. It isn’t a mere “trumping” as though Jesus is simply greater than Caesar; it is an entirely different sort of kingship.

As heirs to Jesus’ kingdom, we are ambassadors of the new reign, privileged to share the mercy, love, peace, and justice of Christ with the world. In the early days—the first century of the Jesus movement—the church was invisible to most people in the Roman empire. However, they had a growing reputation as an alternative and seemingly anti-social community that lived in the nooks and crannies of Empire.

Christians were thought to be extreme, subversive, stubborn, and defiant. The Roman writer Tacitus called them “haters of humanity.” They rejected the central facets of Roman religious and political life. In his view they actively undermined society with their indifference to civic affairs. Some critics even blamed Christians for the fall of Rome.

So, when Jesus said his kingdom wasn’t of this world, he wasn’t understood by Pilate or by the Jews or by his earliest followers as talking about the afterlife or some abstracted spiritual truth. Based upon the lethal response to Jesus (and the early reactions to Jesus’ movement), the “Kingdom of God” was understood as a challenge to Caesar and his reign. Their two kingdoms clashed.

The kingdom of God that Jesus announced and embodied is what life would be like on earth, here and now, if God were king and the rulers of this world were not. As we read the Gospels, we are invited to imagine what it would be like if God ruled the nations.

But in order to imagine that, we’d need to recognize that Jesus’ kingdom isn’t the sort that one holds with an iron fist. Rather, it is an unkingdom. We may have inherited a cruel and domineering of God, but Jesus us reveals to us a God who rejects hierarchy or control.

Where the President of the United States insists on a troop surge, Jesus calls people to love their enemies. When he demands a wall, Jesus calls us to embrace strangers and aliens. Where dictators seek to secure their own power and prestige, Jesus calls people to serve one another and lay down their lives for friends. Since Jesus is (as Christians believe) the truest revelation of God, then he defines for us what the reign of God looks like.

The social, economic, political, and religious subversions of such an reign (or un-reign) are almost endless—peace-making instead of war mongering, liberation not exploitation, sacrifice not subjugation, mercy not vengeance, care for the vulnerable instead of privileges for the powerful, generosity instead of greed, embrace rather than exclusion.

In a very real and disturbing way, Jesus is calling for a loving anarchy. An unkingdom. Of which he is the unking.