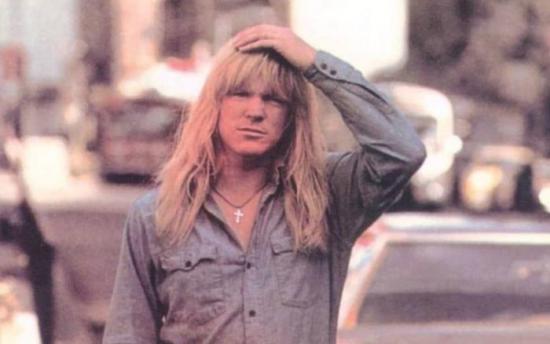

Possibly the most prominent figure of the 1960s Jesus Movement, Larry Norman single-handedly started the Christian rock genre. A provocateur who rubbed shoulders with Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin and The Who, he had mainstream success even though his songs were about Jesus, and in concert he seemed more concerned with pricking his audience’s conscience than giving them a rollicking show. Today, it’s almost unheard of for a Christian rock star to be embraced by both the evangelical and “secular” worlds; Norman found success and controversy in both.

The first time I ever heard his name was in the mid-1990s. I was attending a dc Talk concert at the Palace of Auburn Hills when the trio launched into their now-famous rendition of Norman’s Rapture-ballad “I Wish We’d All Been Ready.” As a kid terrified of being left behind, the song left a mark. While I only recently got around to listening to Norman’s work, I was a ‘90s youth group kid who soaked up the culture he helped create. Without Larry Norman, there would be no dc Talk, Michael W. Smith, Audio Adrenaline or Rich Mullins. The fascinating thing is that Norman, who was often frustrated by the evangelical world, might have been okay with that.

Norman’s the subject of Gregory Alan Thornbury’s new book “Why Should the Devil Have All the Good Music: Larry Norman and the Perils of Christian Rock.” The book is a fascinating look at the mercurial singer and his often complicated relationship to faith and fame.

These days, faith-based art is everywhere. As I write this, you can head to the movies and choose between “I Can Only Imagine,” “God’s Not Dead 3” and a film about the life of Paul. This past Sunday, NBC scored big ratings with its broadcast of “Jesus Christ Superstar.” The Christian music scene has been a multimillion dollar industry for decades.

The problem? Not all of it is good and some of it is justly derided. Rather than engaging the world, it pushes further into isolationism and comes off not as art for the soul but product for the pious. Reading Thornbury’s book, I was struck by what an anomaly Norman was and the lessons he might have for Christian artists, 10 years after his death.

Be Good

Prior to reading Thornbury’s book, I was unfamiliar with much of Norman’s music. I’d heard his original take on “Why Should the Devil Have All the Good Music” (later redone by Geoff Moore and the Distance), but any other exposure to his music had come through covers. As I grew older and aged out of my CCM days, I chalked up Norman’s music to being of the Maranatha/Gaither variety. I assumed it was a pale shadow of what we heard on mainstream radio and had only gained popularity because of the hippie Jesus Movement.

Reading this book caused me to rethink those assumptions and pull some of Norman’s recordings off the shelf (er, the Spotify). I found an artist whose music was compelling and often strange. It wasn’t “safe,” and it didn’t sound like anything I was familiar with. There was, of course, something Dylanesque about it, but only because Norman and Bob Dylan were contemporaries.

“Only Visiting this Planet,” Norman’s sophomore album, is one of the best Christian albums I’ve heard. It’s an eclectic mix of love songs, societal ruminations and angry prophecy. There is poetry to the lyrics (“Pardon Me” is a haunting, embarrassingly earnest ode to love and sex) and the music runs the gamut from folk to ballad to rock. It sounds fresh and vital, even more than 40 years after its release.

That’s an odd thing to say about modern Christian music, which too often apes fads to provide an alternative to what’s playing on the radio or MTV. I worked at Family Christian Stores for several years, and we had a large chart that told people what CCM bands were comparable to their favorite mainstream bands (ex. “If you like Green Day, you’ll love Relient K”). While I’ll defend some Christian rock, the truth is that much of it sounded like a copy of better music. The difference, of course, was that the lyrics were cleaner, substituting “Jesus” for “baby,” as the old joke goes. Ostensibly, the goal was to introduce mainstream artists to Christ through music, but the truth is that it just provided further reason for Christians to isolate and form their own culture. Those who liked Green Day could just listen to Green Day. Besides, they were too often turned off by the preachy lyrics.

Norman wouldn’t have taken umbrage to this description of most Christian music. He was one of its biggest critics, stating:

Music is a powerful language, but most Christian music is not art. It is merely propaganda. It never relies on — in fact it seems to be ignorant of — allegory, symbolism, metaphor, inner-rhyme, play-on-word, surrealism, and many of the other poetry born elements of music that have made it the highly celebrated art form it has become. Propaganda and pamphleteering is boring, and even offensive unless you already subscribe to the message being pushed…which is why Christian records only sell to Christians.”

When I was regularly reviewing films, my Christian friends would often ask me if I’d seen the latest “God’s Not Dead” or other faith-based films. My answer was often a polite no, but inwardly I was recoiling. I knew the reputation that most Christian movies had. They were bad. They were poorly made, badly acted and often preachy to the point of offensiveness. I would rather point a filmgoer to a movie that was made with quality and passion, even if it was sometimes theologically shaky, than to have them take in bad art that just wanted to get a point across. After all, the best art provokes questions instead of preaching. Christians made in the image of a creative God should be honoring him with quality, imaginative art. And if you can’t make a film entertaining or music listenable, people simply won’t stick around to hear what you have to say.

Norman believed this. He was dedicated to making quality music first, believing no one would listen to him if his art was subpar. The artists he signed to his production company were expected to undertake a yearlong mentorship program to ensure that they produced innovative, artistic works. Particularly in his early years, Norman pushed the bounds of creativity, even when it put him at odds with the Christian community. In doing so, he angered some and angered others. But he also gained the respect of many in the music industry, including Dylan and Paul McCartney. They were willing to listen to what he had to say because they respected him as an artist. I wish today’s Christian artists were as disciplined about quality.

Be Provocative

As stated above, Norman knew that the majority of Christian music finds its way into the hands of people who already subscribe to the artist’s message. As the Jesus Movement grew, it began to be corporatized, the way many of the hippie movements did. Christian music became an industry, and Norman found himself singing for Billy Graham, of all people. But he didn’t become buddy-buddy with the church.

Instead, Norman saved some of his harshest criticisms for fellow believers. He attacked hypocrisy and held other artists to high standards, some of which he was unable to keep. He challenged Christians’ attachment to their country and politics. He made them confront what the words of Jesus actually meant.

If you listen to “Six O’ Clock News” or “Great American Novel” today, those songs haven’t aged a day; they’re still equally confrontational and angry in an age of 24/7 media and an evangelical community that’s traded in conviction for political power. Norman believed that if art by Christians was going to be consumed mainly by Christians, it had to dig deeper than simple praise and worship or seeker-friendly sermons. Norman wrote Christian protest music that sought not to make audiences comfortable but instead get under their skin and make them examine whether their actions lined up with their beliefs.

We desperately need this today, in an age where the majority of Christian music offers positive pats on the back that comforts and encourages. There’s certainly nothing wrong with that, at times. But if we believe our faith is holistic and good for every situation, we must be aware that at times it won’t be positive or comfortable. If Christians are supposed to come together to grow in love and be more like Christ, that will often require art that includes lament, conviction, confession and prophecy. Sometimes it will prick at us and drive us to our knees instead of warming our hearts and having us raise our hands.

Contrary to what some may believe, I’m all for art that is made for Christian audiences. Every community has its own needs and nuances that art can engage. But, like Norman, I believe that if art is going to preach to the choir, it must dig deeper. Instead of movies, books and music that only evangelize, we need to move from cultural milk to cultural meat, with art that engages deep theology and holistic Christianity. We need songs that protest, films that lean into our questions, books that encourage us to think deeper.

We need worship music, yes. We also need songs of lament. We need films that ask hard questions, where the football team loses, the marriage fails, the baby is stillborn and the pastor questions whether God is still listening. We need protest lyrics that make us confront our love of guns, our trust in politicians, our callousness toward the unborn. Christians need to be encouraged to create art that serves as confession of sin and grapples with doubt. We need comedies that allow us to see our faults, dramas that address marriage and sex, and music that is creative and experimental because we serve a creative and experimental God.

It’s not that Christians don’t deserve an artistic niche. It’s just that God deserves a better one.

Be Flawed

Thornbury’s book is far from hagiography. Its greatest success, in fact, is its picture of a complex figure. Larry Norman was a man of contradictions. He sung about love but was often at odds with his fellow musicians, producers and managers. He wrote about Christ but had a contentious relationship with the Church. He preached purity and wrote about our culture’s problem with sex, but his first wife was promiscuous and modeled for scandalous photos; it’s alleged that Norman had a son he never openly acknowledged.

Larry Norman was a flawed man. One of the fascinating things in Thornbury’s work is how the mainstream press often saw him as a figure who modeled Christianity, but Christian media often looked at him suspiciously, even doubting his health problems late in life. It seems that the flaws that made him so accessible to those outside the faith made those inside the circle maintain their distance.

That sounds a lot like the Christian world I know. We want our pastors to be unwavering in their convictions and our artists to be models of purity. We often expect our friends who don’t share our beliefs to be flawed; we tut-tut the slightest misstep in fellow believers.

But one look at our Bible shows not a long line of revered holy men but a millennia-long history of adulterers, hypocrites, murderers and warmongers. David took advantage of a woman in his kingdom and then had her husband killed. Noah was a drunk. Peter was a hot-head when Christ walked the earth, a racist when he didn’t. Paul murdered Christians before his conversion, and questions still remain about how misogynistic he may have been. In the 2,000-year history of Christianity, there’s been exactly one perfect individual.

And yet, we hate to acknowledge that. We bristle when people make jokes about churches being filled with hypocrites, even though the teachings on sin should make that apparent. We hide our struggles with lust and anger, swapping them out for more ‘acceptable’ sins like pride, avarice and gluttony. We point fingers at our sinful culture, not realizing the Gospel points three more back at us. And we turn our back on flawed saints because we believe that their behavior doesn’t line up with the story we’re telling the rest of the world; their struggle is bad marketing.

And yet if we believed the Gospel, we wouldn’t be surprised when some of our most public leaders and artists struggle with the temptations of acclaim and celebrity. Maybe we’d realize that our self-righteousness and pretend piety often makes us appear isolated and aloof from the people we’re called to love and serve. And maybe we’d be more thankful for men like Larry Norman, who lived with imperfect passion and flawed creativity simply because their love for Jesus made them reckless.