This post is part of a weekly series focused on the National Geographic Channel’s documentary miniseries “The Story of God with Morgan Freeman.” I’ll be tackling the topics of that series from a Christian perspective over the next few weeks, usually by Tuesday night or Wednesday morning. This post is based on the next episode, “Apocalypse,” which will air on 4/10 at 9 p.m.

I think most evangelicals go through a Rapture obsession.

I remember when it happened for me. I was 15 and my parents had taken me to a dc Talk concert. During the show, the trio played a cover of Larry Norman’s “I Wish We’d All Been Ready.” When the group got to the last verse of the song, what had been a light-hearted, energetic show suddenly chilled me to the bone:

The Father spoke, the demons dined

How could you have been so blind?

There’s no time to change your mind

The Son has come and you’ve been left behind

I wish we’d all been ready

I’d been raised in a Baptist church since infancy, so I knew that my family believed in the Rapture — the time when many Christians believe Christ will take His living and dead followers up to Heaven. According to that interpretation of Scripture, nonbelievers will remain to suffer through a period of suffering (the Tribulation) that culminates in the reign of the Antichrist, the battle of Armageddon, the fiery destruction of the planet and, ultimately, the Final Judgement. I’d heard about this for years, but this was the first time I began to consider its implications.

Would I be alive when Christ returned? What if I wasn’t truly saved? Would I be left behind? What would it be like for those who were? I had nightmares of friends and family suffering catastrophic war, giant locusts and continent-demolishing earthquakes.

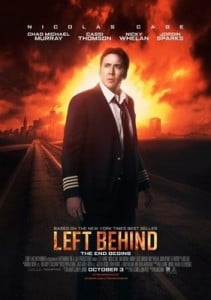

A few months later, Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins published the first “Left Behind” novel. Like many other evangelicals, I devoured it. I also read other books that promised to unlock the code of Revelation, listened to church leaders theorize about the Antichrist’s identity — often the Democratic presidential candidate — and sometimes jumped if I heard something that sounded a little too much like a trumpet.

This wasn’t a new fad. Hal Lindsey ignited Christian culture’s end times obsession with his 1970 book “The Late, Great Planet Earth,” which theorized that the Rapture and Tribulation could play out in the ’70s and ’80s (spoiler alert: they didn’t). Russell S. Doughton’s “A Thief in the Night” and its three sequels depicted the Rapture and Tribulation for Christian filmgoers several decades before Kirk Cameron and Nicolas Cage were left behind. And any time a new war or global conflict occurred, writers found a new way to link those events to the Biblical warnings of trumpets, seals and horsemen — all for a price. Rapture culture is so pervasive that even Homer Simpson got in on it.

It’s easy to understand the evangelical obsession with the end times. We love doomsday stories, and Earth under the Tribulation is the ultimate dystopia. It’s the perfect plot for a movie, complete with apocalyptic weather, a world war and supernatural beasts; it’s no wonder Christian bookstores are filled with Rapture films and books. Plus, there’s a smug satisfaction evangelicals get from Rapture narratives. Not only do the bad guys get judged, but we don’t have to suffer; we get to sit on a cloud in Heaven watching the show.

Two decades after that concert, I’m a bit chagrined about how into all of this I was. Many Christians, including myself, actually believe “Left Behind” is way off base. The word “Rapture” doesn’t appear in the Bible at all. The idea of Christ coming to rescue believers before the Tribulation was popularized by an Irish priest in the 1800s. While Christians do believe Christ will return, judge the living and the dead, and bring Heaven down to Earth, we’re a bit muddy on how that all works. Some still believe in a pre-tribulation Rapture; others believe it might happen afterward or halfway through. Still others believe that Revelation is symbolic of events that have already happened, or is both a warning to the early church and a political allegory. The ominous number 666 conjures pictures of tattoo’d barcodes in some believers’ heads, while others believe it’s actually a reference to Caesar Nero, who was persecuting Christians around the time Revelation was written.

The truth is, I don’t know how the world is going to end. I also don’t know when it’s going to end, or if I’m going to be around to see it. I’ve stopped worrying or trying to figure it out. As a Christian, I rest in Jesus Christ and His finished work. If He chooses to take me away before things get bad, through death or Rapture, I’ll welcome it. But if it’s His plan for me to endure the Earth’s final days, I believe that He’ll give me the strength to do that as well. My job is not to try to predict events or look for hidden Bible codes. My job is not to fear the end times or pray for judgement. My job is to trust.

And to hope, which is something that goes missing in all the Rapture obsession.

In a culture that peddles fear and tension, end times theology has taken on a grim tone. Yes, the Bible says that things will get dark before Christ’s return. And looking around our world, it’s easy to see violence and disaster everywhere and wonder just how much worse it’s going to get. Admittedly, sometimes it feels like I’m just waiting for God to step in and say, “Time’s up.”

But what gets lost in the Rapture hysteria is that the promise of Christ’s return is not one of destruction, but of renewal. It’s a reminder that no matter how dark this world gets, there’s coming a day when Christ will make it right. This world might be destroyed by war, but it will be renewed by love. Oppressive regimes will be wiped away, replaced by a good king who’s died for his subjects. Sickness and death will be replaced by a life more vivid and vibrant than anything we can imagine. Revelation ends not with a war but with a feast. Not with enemies, but a family. Not with screaming, but with singing.

Contrary to media portrayals — and, very often, our own words — Christianity is not about licking our lips and waiting for our enemies’ annihilation. It’s about believing a truth so beautiful that we want the entire world to believe it: God has made a way for us to know Him. Many times when I was younger, I wondered why Jesus didn’t just take the disciples with Him to Heaven and end the story there. Why wait several millennia to return? It’s only been in recent years that I’ve discovered two reasons. One is that we know this world is a mess, and Christ’s followers are tasked with making it less messy. We have the job of preparing for the king’s arrival by pushing back the effects of sin. We’re called to love and serve others, live peacefully, take care of the planet, and pursue justice. And the other reason? Christians believe in “the more, the merrier.” We believe that the reason Christ hasn’t returned isn’t because He’s lazy or slow, but because He’s patient and has given us time to reach the world with His message. Those two things drive missionaries in every corner of the world and should be the beating hearts of our churches. That — not politics, morality or nationalism — is the heart of evangelicalism.

One thing that Morgan Freeman mentions at the end of the episode is that the word “apocalypse” doesn’t mean annihilation or ending. It’s actually a Greek word that means “unveiling.” And these days, when I look out at our world and think of what my faith tells me comes next, I’m no longer filled with fear, but with hope and expectation. For the Christian, the apocalypse isn’t the war to end all wars. It’s the wedding to end all weddings, and the start of the true story we’ve been preparing for all of our lives.It’s not an end; it’s the beginning of forever.

Read the next post in this series: “Who is God?”