Last evening, as news spread of the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, social media predictably lit up with reaction. Admirers hailed her as an icon of the fight for equality and an inspiration to those who must carry on with their duties even as they suffer grave illness.

Last evening, as news spread of the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, social media predictably lit up with reaction. Admirers hailed her as an icon of the fight for equality and an inspiration to those who must carry on with their duties even as they suffer grave illness.

Public officials on both the political left and right stepped up to offer condolences and commentary. Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden called Justice Ginsburg, “an American hero, a giant of legal doctrine, and a relentless voice in the pursuit of that highest American ideal: Equal Justice Under Law.” Donald Trump, in an official statement, refrained from his usual incendiary rhetoric and said of Justice Ginsburg that she was a “titan of the law” and was “renowned for her brilliant mind.” (Whether either or both men had help in preparing their statements, we can’t deny both statements were appropriately respectful.)

Needless to say, given the political stakes involved in choosing Justice Ginsburg’s successor, some officials couldn’t refrain from releasing news that they plan to try to confirm a Trump nominee before the end of the year (and the end of term for the U.S. Senate, which may change hands after the election in November). Senate Majority Leader, Mitch McConnell, while nodding his head in the direction of Justice Ginsburg’s survivors, saying that “the entire nation … now grieves alongside her family, friends, and colleagues,” pledged to give Trump’s nominee the Senate hearing and vote he refused to give President Barack Obama’s nominee Judge Merrick Garland in 2016 after the death of Justice Antonin Scalia.

This is but a small sampling of official statements in response to Justice Ginsburg’s passing. I offer them here as necessary context, but I’m more interested in looking at a sampling of responses from conservative Catholics, who identify as pro-life and opposed Justice Ginsburg’s legal opinions on Roe v. Wade in particular and abortion legislation in general.

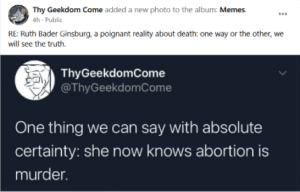

Thy Geekdom Come, produced by a Catholic cartoonist devoted to offering “family-friendly Catholic comics,” tweeted “pray for the soul of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.” Not content to finish there, he continued, “… and also that she is replaced by Amy Coney Barrett because honestly that’s the storybook ending here.” Still not finished, he followed up with a tweet that he cross-posted to Facebook: “One thing we can say with absolute certainty: she [Justice Ginsburg] now knows abortion is murder.”

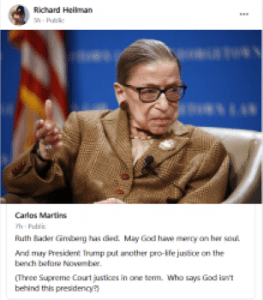

Richard Heilman, a Catholic priest of the Diocese of Madison (Wisconsin), wrote on his personal Facebook page: “The Feast of Trumpets [Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year] began at sunset. Just as the announcement of RBG’s passing came. I’m in prayer and reflection.” Within a couple of hours of his notice that he was “in prayer and reflection,” he had reposted a Facebook post by Carlos Martins, a priest of the Companions of the Cross, a Society of Apostolic Life, in which Martins reflected on Justice Ginsburg’s death, saying, in part: “Three Supreme Court justices [to be nominated by Donald Trump] in one term. Who says God isn’t behind this presidency?” In the context of Justice Ginsburg’s death that very day, it’s hard not to suspect that Martins thinks Ginsburg’s death is proof that God endorses Donald Trump.

Leila Miller, a conservative Catholic blogger and influencer in Catholic social media, tweeted Donald Trump’s initial reaction to Justice Ginsburg’s death, a short sound-byte in which the only adjective Trump could think of to describe Ginsburg without the help of speechwriters was “amazing” (which he used four times in a response of less than a minute). Miller said nothing about Ginsburg’s passing, merely describing Trump’s reaction as “respectful.”

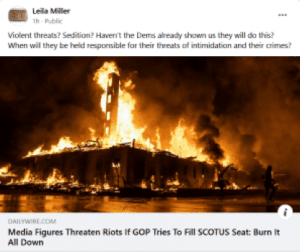

On Facebook, Miller didn’t bother to express personal sorrow, condolences to those who mourn Justice Ginsburg, or even a perfunctory “RIP.” Rather, she focused on attacking Democrats, pointing to an inflammatory tweet by Reza Aslan, an Iranian and American academic who specializes in religious studies, saying of Aslan, “He seems nice. I wonder what political party he belongs to?” She then turned her attention to an essay posted at the conservative media site, The Daily Wire, which is already stoking right-wing panic with the headline: “Media Figures Threaten Riots If GOP Tries To Fill SCOTUS Seat: Burn It All Down.” Miller commented, “Violent threats? Sedition? Haven’t the Dems already shown us they will do this? When will they be held responsible for their threats of intimidation and their crimes?”

Naturally, Catholics and pro-life advocates who aren’t public figures have also jumped on their social media platforms to react to Justice Ginsburg’s death. Friends reported to me that they’d seen comments expressing sentiments such as “praise the Lord” and “rest in piss.” A Catholic I’ve known personally for years left this comment on my Facebook post about Justice Ginsburg’s death: “May she RIP. I’m hopeful this opens a seat to overturn the unjust Roe v. Wade.” I stared at that comment for a full five minutes, wondering what I could possibly say in response. Finally, I decided the most charitable response I could give was to unfriend that person.

When a public figure dies, there’s an understandable temptation to react to the news in a manner that reflects how we related to that person. If we admired the person, we praise the good they did and express sorrow for our loss. While we hope we remember to express condolences to the survivors of the deceased person, they’re not usually our first concern. All too often, we’re our first concern, our feelings and personal agendas taking precedence. That may explain why people who ordinarily may be decent human beings devolve into expressing indecent sentiments when the deceased is someone they either didn’t agree with or actively disliked.

However natural such a response might be, Catholics are called to rise above the natural and strive to respond to Christ’s call to “be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect” (Matt. 5:48). In his letter to the Romans, St. Paul gives some practical advice on how to strive for Christian perfection:

Rejoice in your hope, be patient in tribulation, be constant in prayer. … Bless those who persecute you; bless and do not curse them. Rejoice with those who rejoice, weep with those who weep. Live in harmony with one another; do not be haughty, but associate with the lowly; never be conceited. … Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good (Rom. 12:12, 14–16, 21).

How can we apply this to creating a response to the death of a public figure? Here are some suggestions:

It’s not about you. If you didn’t know the deceased beyond that person’s public reputation, then your own feelings about that person’s death are far less important than the feelings of those who did know and love that person. Don’t say anything about a deceased person that you would be ashamed to find out his or her survivors found out about. For example, before offering commentary on a public official’s passing, think about how you might feel if someone attending your mother’s funeral casually commented that they hope that your mother’s death means that her job will now be available for someone else to perform. Are you going to feel any less devastated if they preface that remark with “I hope your mom rests in peace”?

Find something positive to say about the deceased. Very few people live lives of evil incarnate, making them unfit for anything but revilement when they die. Most people, even those we have reason to dislike, are more good than bad. There is almost always some aspect of their lives for which you can express sincere admiration. In Justice Ginsburg’s case, you won’t lose one iota of pro-life cred if you talk about her accomplishments as a trailblazer for women, or her long, happy marriage, or her friendship with conservative icon, Justice Scalia.

Offer prayers—full stop. In the examples I gave in this essay, several of the commentators remembered that it’s a spiritual work of mercy to pray for the living and the dead. So, they started there. The problem was that they didn’t stop there. If the only thing you can do for someone you can’t say something kind about is to pray, then pray and do nothing else. It’s not that hard to tweet, “I just heard Justice Ginsburg died. ‘For the sake of his sorrowful passion, have mercy on us and on the whole world'” (quoting the Divine Mercy chaplet).

Bury the dead. Most Catholics know that prayer for the living and the dead is one of the spiritual works of mercy. They often forget that the corresponding corporal work of mercy is to bury the dead. “Burying the dead” isn’t limited to grave digging. It can refer to participation in all of the rituals surrounding death. With a public figure, you can watch a televised funeral, write a letter of condolence to the family, or make a donation in the name of the deceased to a cause that mattered to the deceased (you get no credit for spite donations to causes the deceased would have hated). You can even observe a form of “a moment of silence” by refraining from criticizing the deceased until after she’s been buried.

Be kind to those who admired the deceased. You may never get a chance to directly offer condolences to the family of a public figure. But you can offer those condolences to people you know who are feeling the loss, even if that sense of loss is of a much lesser degree than immediate survivors. If a Facebook friend is expressing sorrow over the death of a public figure, your friend doesn’t want to hear how much you disliked the person he or she is mourning. All you have to say is, “I’m so sorry. I know how much you admired her.”

(Images: Angel statue, Pixabay. Screenshots from public Facebook posts.)