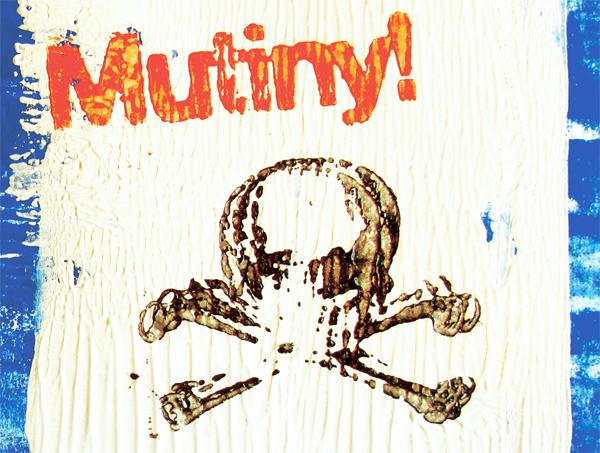

It’s Talk Like a Pirate Day today, and I’m excited to recommend the best possible book for this auspicious occasion — Kester Brewin’s latest Mutiny!: Why We Love Pirates and How They Can Save Us.

I confess I’m only about a third of the way through, which means I’ve already traversed the first two dense chapters filled with rich pirate history. In chapter three, Brewin is beginning to steer the ship into the open waters of the wider implications of this notion of “piracy” for the modern day.

The parallels and connections to the recently revived Occupy movement are very interesting. Everyone involved in or simply interested in Occupy (and we should all be interested, I think!) should certainly read Mutiny! for a primer on the history of where “pirate” movements like that come from and what their true nature is.

Fans of Brewin’s friend and compatriot Peter Rollins will be well served to discover Brewin’s books and blog and add them to their own booty of brilliant theological reflection.

Here’s a taster of Brewin’s Mutiny! (a full review will have to come later):

“We are all pirates now because, in these times of increasing corporate greed, cultural privatisation and financial oppression the fight that was once theirs has now become ours. … True pirates — not common thieves or extortionists — function not just as economic bandits, but also as cultural heretics. Their rebellion is not simply about fair trade, but unjust social structures. … Pirates emerge to rise up against inequitable monopolies and the violent systems of oppression and do so to free the flow of goods and information ‘for the benefit of the poor.’ …

“The idea that the central core of our labour, sustenance, leisure and social life should be based around a space that was outside the bounds of private ownership, which we had to share with others, is so foreign now. But we are exception rather than the norm, for life centred on a commons has been the default human way for thousands of years across virtually every culture. …

“If the commons was the theatre in which the life of the community was played out, it is only in the past hundred years that we have seen that stage reduced into a tiny living room behind a locked front door with space only for a nuclear family, a television, and piles of commodities, things we have bought in the vain hope that the ache of our separation will be dulled.

“The things we buy do dull the ache, but only for a short time. Once the new devices and clothes hae been unboxed and hung in wardrobes and connected to networks, the ache returns again, and it does so because it originates in the human history of shared existence and common ownership which far precedes the modern idea of private property. Hidden beneath our heavily enclosed world, with its high fences, encrypted DVDs and lengthy copyrights, there still hangs over an ancient sense within us that our lives shine most brightly when shared with the lives of others, and become most meaningful in the spaces beyond the objects we consume behind closed doors. …

“This, then, is what we can take ‘pirate’ to mean: one who emerges to defend the commons wherever homes, cultures or economies become ‘blocked’ by the rich.”

What do you think of Brewin’s notion of the “pirate” and how it relates to missional living in our time and our place? Challenged? Confused? Critical?