“I don’t think there’s ever been a time in my life when I wanted to pray. My mom always made me think that as Muslims, we should. But as soon as I stopped caring about what Mom thought, I stopped praying altogether. But today—right now—I really want to pray.” (Rebels by Accident, p. 150)

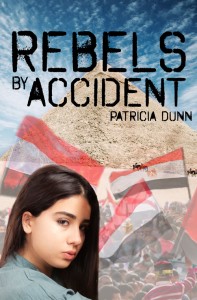

Rebels by Accident introduces us to Mariam, a 15-year-old Arab-American teenager who finds herself in jail after police raid a party she had crashed with her best friend, Deanna. Her horrified parents punish her for this first act of “rebellion” by sending her to Egypt to stay with her paternal grandmother, Sittu, a woman known to her only as someone strict and uncompromising. It is in Egypt where the story unfolds. Under the careful watch of Sittu, Mariam and Deanna are thrust into a foreign culture, where through a series of adventures (visiting the pyramids, going to the mall, ice-skating), the girls come to realizations about who they are as individuals. It is also within the backdrop of the political revolution, exemplified by the mass gathering at Tahrir Square, where “surrounded by thousands of protestors, Mariam finally embraces what it means to be American and Egyptian.”

Author Patricia Dunn joins a growing number of Muslim writers to publish young adult (YA) novels that feature Muslim female protagonists who are neither portrayed as nameless victims nor some veiled, orientalist fantasy in need of saving. It is not too farfetched to suggest that Rebels By Accident is part of a new wave of YA novels featuring Muslim girls whose stories join other teen voices grappling with issues of identity, sexuality, religion, and a myriad of “first times.” These themes are exemplified in books that include (among others) Does My Head Look Big in This? by Randa Abdel-Fattah, which according this post represents a new trend in YA fiction, where the Muslim protagonist isn’t depicted as a terrorist. Another is The Shadow Speaker by Nnedi Okorafor-Mbachu which exemplifies a good sci-fi story featuring a strong, female protagonist who is Muslim. Other books focusing on the experiences of Muslim girls include Ten Things I Hate About Me, Ask Me No Questions, Skunk Girl and A Map of Home.

The real question, however, is where Rebels By Accident stands in terms of building understanding and or reinforcing stereotypes about Muslim girls in popular YA fiction. Thankfully, the book avoids the “save the Muslim girl” narrative described by authors Özlem Sensoy and Elizabeth Marshall (Part 1, 2 and 3), who write about Muslim girls being often portrayed as veiled, silent, oppressed, and in need of saving. Mariam does not veil (and the subject matter crops up only briefly, and as a way to break stereotypes of veiled Muslim women). Nor is she a silent victim – the title of the book already hints to the young woman’s struggle as a Muslim American caught up in another “rebellion” all together.

In a Q & A supplement from the official press kit, Dunn discusses why she wrote the book. She recounts an incident on a bus, where her son was hit on the head and basically ridiculed for being a Muslim American. She says,

“I hope this book helps Muslim teens, like my son, or any teens that have ever been bullied or ostracized because of others’ ignorance, understand that they are okay and it’s the bullies who need to change.”

While the book appears to be targeted towards Muslim Americans, international audiences will also appreciate the manner in which the author has addressed the politics of identity through the actions of the protagonist, Mariam. In my experience, within predominantly Muslim countries, being Westernized and having a predilection for the English language is sometimes perceived as a sense of entitlement and disconnect with one’s cultural heritage. The growth of Mariam’s character throughout the book, particularly through her actions and thought processes of someone coming to grips with her ethnic and religious background, can be eye-opening for those not aware of the challenges facing young adults with such complex backgrounds. Mariam’s trip to Egypt allows her to understand that Sittu is far from the scary authoritarian that Mariam’s father has described. Nor is Egypt just “pyramid land” (p. 14) where “women are second-class citizens who take orders from men and have to cover their hair because the men are so perverted they can’t be trusted!” (p. 16). In many ways, the character of Mariam is representative of those ignorant of Islam and the fallacies that exist between its teachings and the patriarchy that actually condones women’s suppression. Additionally, for others, especially Muslim Americans, these are struggles many face every day and it helps that such delicate subject matter has found additional focus and support in Dunn’s capable hands.

While reading this book, I was reminded of those Scholastic YA books I had read growing up. The only difference is that this time around, instead of featuring blue-eyed, blond protagonists in stereotypical settings where the young adult is exposed to changing circumstances that result in a lessons learned, this book features a young American Muslim woman who’s sent to Egypt for a few days, and where she learns a little bit about her country and culture, and even experiences a first kiss. None of my Scholastic books featured overt references to religion except during scenes where an elderly grandparent or important parental figure passes, all of which is often used as a plot device to keep the drama moving forward. In Rebels By Accident, religion is actually central to the overarching theme of the search for independence.

Initially, my only real critique of the book was that there is so much happening in terms of plot that certain characters appear less developed than others. For instance, both girls have love interests but neither of them seemed fully convincing in their roles as potential boyfriends. After completing the story, I realized two things. Firstly, the girls are in Egypt for barely a week. That means much of the plot takes place over a very short period of time, and the interaction with the young men in terms of dialogue and character development becomes limited too. Additionally, the love interest dimension of the plot echoes a lot of other writing of teenagers as hormonal balls of angst in a perpetual state of ennui, and falling in love (much like everything else they experience) occurs quickly and with almost overtly dramatic consequence. This is something to keep in mind when you (the reader) are introduced to Muhammad and Hassan, the enigmatic, good looking boys that keep you vested in a happy ending and provide us with the requisite drama in terms of who ends up with whom!

Personally, I wish YA Muslim fiction had been around when I was growing up since much of what I read comprised of titles by R. L. Stine, Judy Blume and Caroline B. Cooney. Having said that, while these books were a fascinating look at a culture not wholly my own, the stories of “awkward adolescence” are a common thread unifying all YA novels. Rebels By Accident is not just for teens; it’s for anyone who appreciates a good story about love, family and growing up in an increasingly diverse world. I would recommend the book for the humor alone. Look forward to some poignant one-liners from all characters, several of which I’m sharing below:

Mariam: “They expect me to stand up in front of the whole school and talk about Egypt? Like I don’t get enough shit because everyone sees me as some freak from pyramid land.” p. 14

Deanna: “That’s the same woman I was just talking to; now you see her, now you don’t. She slips the black cloak over her head and presto, change-o, she’s gone.” p. 29

Mariam: “Not strict enough? It already feels like I’m living a life sentence. My only fun is reruns and reality TV. And that’s if my parents aren’t around to tell me to turn it off because people like Snooki on Jersey Shore act inappropriately. Of course she acts inappropriately! Who wants to watch some good girl on TV?” p. 13

Marium: “Can a dress actually make your nose look smaller?” p. 55

Sittu: “Habibti, you never stopped being Muslim. Maybe you stopped praying and doing the rituals, but you’re a woman who shows compassion and love for others. I see how much you care for Deanna. That is what it means to be Muslim.” p. 182