Over the past few years, I have been quite interested in Chinese Islamic practices. Part of it comes from my own Chinese ancestry, which is often clouded by strong Mexican traditions and marital institutions. Although today my mother’s family acknowledges that my great-great-grandfather was Chinese, a few decades back, no one was thrilled to admit that my great-great-grandmother engaged in an extra-marital affair with a man who “used to bow to pray,” as my great-grandaunt says.

Although I will probably never know if my great-great grandfather was Muslim, the shadow of this sea merchant (that’s as much as we know about him) who randomly happened to make a stop in Mexico and produce two kids within two years, has followed my family around for generations. Years later, after my conversion to Islam, I started wondering if the “bowing prayers” were part of the Islamic salah?

Chinese Islam is, in comparison to others, rarely discussed in the media. It does not appear as often in articles or blogs, and when it does it tends to be treated as completely different from other forms of Islam.

Hui people are a distinct, predominantly Muslim, group in China (although not the only mainly-Muslim ethnic group in the country). They are concentrated in China’s western provinces (Gansu, Quinghai and Ningxia), and they are officially recognized as one of the 56 ethnic minorities of the People’s Republic of China. Many Hui people are also descents of Arab and Persian traders that followed the Silk Road.

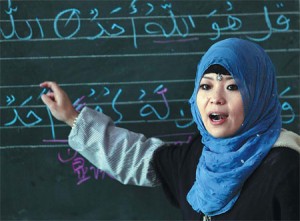

One of the features that is often highlighted in the media about Hui Islam is the existence of only-female mosques. Not only that, but women’s mosques also feature female religious leadership as well as women’s involvement in the community’s matters. This was particularly attractive to me since the woman that my great-great-grandfather hooked up with (my great-great-grandmother) came from a matriarchal society, where women participate in political leadership and religious practices.

Women-only mosques are seen as an orthodox way of opening space for women when it comes to the mosque. Unlike other attempts to bring female presence to the mosque, these mosques do not seem to be too threatening in comparison to having women leading prayers in the West (i.e Amina Wadud or Raheel Raza, both of whom led public mixed congregations) or having all-inclusive mosques, which have caused some unrest within Muslim communities.

Yet, these mosques also face a lot of challenges. They depend almost completely on donations, which can be a difficult way to run a mosque. In addition, some mosques still rely on men’s mosques around the area to lead prayer through loudspeakers, which perhaps also speaks to the status that female mosques hold in the area. Furthermore, China’s quick development and financial opportunities are threatening women’s mosques by providing women with opportunities far from their communities and in non-religious environments, so women’s mosques may not be sustainable in few years.

An article in the NY Times by Didi Kirsten Tatlow sees the Chinese model as a way of inclusion for Muslim women around the world. The article also highlights that female leadership and education in these Muslim communities has been a tradition for over 300 years. Thus, this is not your contemporary Westernized Muslimah supposedly wanting to be like a man (as some would claim), but rather “authentic” Muslim women practicing “authentic” Islamic tradition.

Perhaps the difference is not only that women do not mix with men, but also that this form of practice is seen as “traditional.” The claim that these women have to ancient tradition of leadership and education has given them the opportunity to operate their own mosques and educational programs with some degree of independence.

While I think that the challenges and the status that these mosques hold should be taken into consideration and challenged so they may survive and provide Muslim women with better leadership opportunities, I believe that the idea of an only-women’s mosque is powerful.

An all-female mosque may even be an environment where a lot of Muslim women would not hesitate to participate. No issues with male authority, no problems welcoming children or discussing women’s topics.

Yet, let’s not forget that at the end of the day, as a community men and women have to interact, and for our communities to grow and flourish, we need both. Something that I feel is missing from the discussion in the media is the fact that regardless of the arrangements in terms of space (women’s mosque, segregated spaces, mixed congregations, etc.) mutual recognition should exist.

Women should be recognized as legitimate members of the mosque and should not necessarily be told to “have their own mosque” if they want equal right to leadership. Likewise, in all-women’s space, women should be encouraged to thrive as members of society as a whole, not only among women.

I like to think that mutual recognition was perhaps why my great-great-grandfather and my great-great-grandmother liked each other… possibly it was the understanding of equality and female leadership… but I guess I will never know!