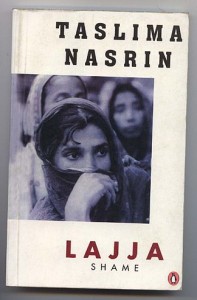

I have been hearing about Taslima Nasrin from the time I was a child. The Muslim Bangla woman was accused of writing blasphemous anecdotes about Islam in her 1993 novel Lajja, which drew a number of protests, including at least one group calling for her death and offering a reward; Lajja was banned in Bangladesh following widespread protest against its contents.

So it was natural that I picked up a copy of Lajja when I recently found it in a roadside bookshop, as it was hard to find a copy in established book houses in India. Nasrin’s work over the last twenty years since the publication of Lajja has been controversial as well, but this post will focus on Lajja specifically.

Lajja is about a Bengali family, the Duttas, who are Hindus by birth, but are atheists in their belief system. The family consists of Sudhamoy and his wife, Kiranmoyee, and their two adult children, Maya and Suranjan. Though the book is written about the 1992 Riots in Bangladesh following the Babri Masjid Demolition, during which there was widespread violent riots in Bangladesh, against its Hindu minority community, it also mentions in detail two other significant events in Bangladesh history:

1. The 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War, which was fought with the State of Pakistan, where Bangladesh fought to become an independent secular state. This is told through flashbacks from Sudhamoy’s experience as a young man.

2. The 1990 Babri Masjid dispute in Ayodhya India, during which large scale communal disturbances were caused in Bangladesh.

The book chronicles the story of the family in the 13 days following the Babri Masjid Demolition. While news of an ensuing riot fills the news channels, Sudhamoy is reminded of his grim experiences during the Bangladesh Liberation war, where he was captured by Pakistanis and tortured. His wife had to stop wearing the Sindhur, which is a compulsory custom among married Hindu women, for fear of being identified . However, following the declaration of Bangladesh as an independent state, Sudhamoy believed all his trials and tribulations would be over. Much to Sudhamoy’s dismay, Bangladesh, which was founded on secularism, was later converted to an Islamic state.

There are constant references to partiality against the Hindus in government offices. Sudhamoy, who is a medical practitioner, is not promoted duly in his jobs; Suranjan, his son, is still unemployed at 33 years of age. There is also mention of Muslims’ general disconcert with music, where Kiranmoyee is treated as unchaste because she sings in public. Despite all of the cruelty and discrimination they face, Sudhamoy and Suranjan find it belittling to leave their motherland and move to India as most of their Hindu relatives and friends have been doing. (The Bangladesh Liberation war led to about 10 million refugees moving to India.) Once the riots reach their door step, the Dutta home is attacked, and the rioters abduct Maya, the daughter, following which she never returns home, and her whereabouts remain unknown until the end of the book. Suranjan, haunted by his sister’s abduction, seeks his revenge, by picking up a Muslim prostitute and physically assaulting and raping her in his home. There is news that Maya’s body may have been discovered; however, Suranjan doesn’t confirm it and chooses to live with the hope that she will return. Much to Kiranmoyee’s relief, Sudhamoy and Suranjan decide to leave for India, unable to suffer anymore, in the name of their motherland.

All through the book, we can see people tortured, humiliated and living in fear for no fault of their own. People who are atheists, and who have fought for the independence of their country, being ostracized due to the religion they were born into. Most importantly, it’s written from a Hindu’s perspective, by a woman of Muslim background. Nasrin’s book is well researched and is interspersed with pages of factual knowledge of the various and immense attacks carried on Hindus by Muslims in Bangladesh all throughout history. It is also written with anger and sadness that anyone who believes in equality, human rights, democracy and secularism, would feel.From a literary point of view, Lajja is an average book, where a new writer is trying hard to bring a riot to life, but is caught up between journalism and fiction. However, nowhere in the book is any reference made to Islam, in a way that should hurt Islamic sentiments. When reading it, I wondered if some of the protests had to do with the graphic description of rape in the book, but it runs for only about three lines, and as this woman’s rights activist points out, the sexual violence in the book is not unrealistic. Islam or the Hadith aren’t quoted anywhere in the book, and it’s hard for anyone Muslim or otherwise to understand why this book was banned. It talks about oppression of a minority ethnic group; it just happens to be that, in this scenario, Muslims are the majority, and Hindus the minority. Nasrin questions the conversion of Bangladesh into an Islamist state, leading to the treatment of Hindus as second class citizens. For this non-Bangladeshi Muslim reader, Lajja reads as an at times boring account of a riot. This book by no means deserves any fatwa, and if left alone, might have been dismissed as average writing, instead of getting so much attention.