This post was written by guest contributor Amina Jabbar.

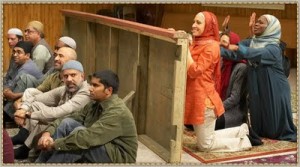

As I was sifting through the internet, blogger A Bengali in T.O. caught me with a personal question: “Where are the Girls in this Mosque?” The women’s prayer space at the mosque he was visiting was completely separated, with no direct view of speaker in the main prayer hall, only connected via a set of speakers and a monitor. In reflection, he aptly noted,

“This is the problem, the big problem, in today’s Muslim organizations. If you take a look at this picture, there is a LOT of empty space behind the men, in the MAIN prayer hall. Why can’t girls sit here, in close proximity to the speaker, so they can personally ask him questions, or be inspired in way that only a face-to-face conversation can?”

Shiri Yusuf provides an equally raw account of that same, familiar struggle to be visible within the Muslim community but just on a more intimate, micro-level. As an educated, British woman, she writes about the difficulties of finding a Muslim husband: “I am a woman who according to culture is very much pass [sic] her ‘sell-by’ date…” She attributes the trend to attitudes taught to young Indo-British men; that Western Muslim women with an education don’t know how to be wives and mothers.

I’ve been trying to read deeply between the lines of both of these entries and the many other articles, accounts, blogs, and documentaries written on the same issues. And there are many, written from a range of perspectives and each offers their own analysis. On mosques, Zarqa Nawaz’s documentary Me and the Mosque offers an analysis still extremely relevant eight years after its release. An article on Mosque Makeovers also offers a broader look at reimagining mosque spaces. On marriages, AltMuslimah and GOATMILK encompass a multitude of views on all aspects of dating and matrimony. While the conversations about women’s spaces within mosques may seem unrelated from those about finding mates, assuming a strictly heteronormative perspective, the subtle undercurrent underlying both media discourses appear to share a similar assertion: Muslim men don’t know how to relate to Muslim women.

I don’t think the dynamics are specific to Muslims or Islam, but are symptoms of a silent, implicit system of patriarchy that is endemic to Western society and seeps into all aspects our lives. Acclaimed writer Junot Diaz has remarked

“I think that most of us are not aware how we have acquired a vision of women that doesn’t really encounter or doesn’t really think of them completely, entirely as human beings…I grew up with this idea that women were either kind of a mom-like figure, someone who did stuff for you, or a figure of your sexual attention. And that doesn’t leave much room in there for there to be more nuanced, more complicated and more human relationships. ”

In other words, the exclusion of women from mosques and marriages are the manifestations of patriarchy and misogyny in the Western, Muslim context.

Few mosques and Muslim organizations, for example, genuinely engage women. Even among those women that do organize within the community, they’re commonly and frequently squeezed out. Wahida Valiante and Asma Warsi, two Muslimah community activists local to Toronto, expressed those sentiments in an interview on Canadian Politics and You (at 15:00 and 30:00). I spend the vast majority of my life in unsegregated spaces, talking to and closely working with men. As Warsi specifically points out, double-standards appear within the mosque context; plenty of Muslim men will shake a non-Muslim woman’s hand. I’ve shaken many hands of non-Muslim men. Yet, I can count the number of times a Muslim man has offered to shake mine, oddly enough, on just one hand.

Scratch beneath the surface and the issues related to finding Muslim male mates aren’t so different. In her article for the Guardian, Syma Mohammed alludes that the growing number of single, Western, Muslim women is attributable to their higher levels of education, professional lives, and careers. She writes:

“Moreover, in line with national trends, Muslim women academically outperform the men. …This means that professional Muslim women have an even smaller pool of intellectual and economic equals to choose from. This is exacerbated by the fact that Asian men are likely to choose partners of lower economic and intellectual status as they traditionally grow up with working fathers and stay-at-home mothers, and generally choose to replicate this model.”

For all the social encouragement to pursue post-secondary education, Muslim men seem mentally stuck with preferences for wives who prioritize the home over the professional. In no way should this suggest that marriage is the yard-stick by which Muslimahs should measure their self-worth, nor that every Muslim woman is dying to get married. An AltMuslimah article, “Chasing life,” itself is interesting and nuanced. But the description of the processes and challenges inherent in getting married for many Muslim women offers a window into the complicated gender dynamics deeply embedded within the community.

To be clear: I write a blunt, critical analysis because I truly, radically love the Muslim men in our community, but I despise the systems of patriarchy and misogyny that infiltrate our Western cultures. I don’t think most men of any community engage in sexist, patriarchal beliefs or behaviours with explicit intention. But that doesn’t preclude men from recognizing and embracing individual responsibilities. I’m not asking men to feel guilty. I’m not asking men to undermine their masculinities. But I am asking our Muslim men to acknowledge that they benefit from pre-existing systems of patriarchy and misogyny at the expense of Muslim women’s place and space within the ummah. For a more pragmatic peek into those benefits, Jamerican Muslimah provides the “Muslim Male Privilege Checklist,” a smart adaptation of Peggy McIntosh’s “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.”

I have lived in Toronto for fourteen years, and the gender dynamics within mainstream mosques feel largely frozen. Every imam I know can defend gender equality in Islam with lightning speed. Meanwhile, we’re praying in the same cramped closets with growing numbers of women who feel matrimonially constrained. Yet, I’m filled with hope because Muslimahs and their male allies have taken to speaking through a spectrum of media. From articles featured in national newspapers to the blogs that scream all that is raw and personal, Muslim women are engaged in the complicated, frustrating discussions that don’t occur within mosques and Muslim organizations but are so critical to women’s lives. Muslim women already light the way to having uncomfortable conversations in productive ways. Muslim men have immense opportunities to learn from that wisdom, only if they choose to genuinely listen to, engage with, and make space (literally and figuratively) for women within mosques and Muslim organizations. Growing genuine, deep, and nuanced relationships with each other creates the path to a vibrant and illustrious ummah. That can’t happen without its Muslimahs.