Pink princess toy cameras. Pink princess wallets. Pink princess magic meal time cutlery. Pink princess backpacks, pencil cases, water bottles, golden hair extensions, and the most fabulous silver sparkle princess shoes with pink flashing lights.

After only a week in full-time school, my daughter Eryn has embraced this new world of marketing around princess culture — and even though she has never seen a Disney princess film, she can now name all of the popular princesses off by heart.

Princess culture is ubiquitous — from their original fairy tales to lego. As an empire, it’s selling a whole slew of negative gendered stereotypes, unattainable beauty ideals, and a message that a woman’s agency and action is found only through her sexualization. Even the most “brave” anti-princess princess of the Disney franchise, Merida, was at one time subjected to a sexy redesign — which was pulled after a huge backlash favouring her original bow and arrow over huge breasts and a sparkly dress. And let’s not forget the problematic Jasmine of Aladdin, our favourite Muslim princess at MMW, who not only falls victim to orientalized cultural stereotypes, but becomes a heroine by seducing the bad guy with a bare midriff, fluttery eyelids and a hawt kiss.

There is nothing wrong with children loving the colour pink or wanting to “sparkle” — but there is definitely more to life than buying into the message that vapid beauty and inaction will help little girls everywhere snag (and be saved by) a rich, hetronormative prince.

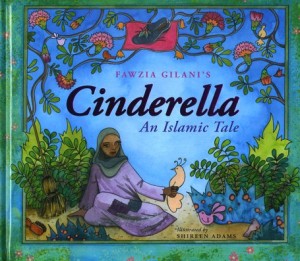

So in looking for alternatives to balance out this growing influence, and to help my daughter find positive examples of Muslim identity in the media she consumes, I was recently overjoyed to find an Islamic alternative to the classic Disney Cinderella story.

Cinderella: An Islamic Tale by Fawzia Gilani-Williams is a wonderful children’s book. Set in medieval Andalusia, the classic tale receives a both religious and pro-woman retelling. The fairy Godmother is replaced by a grandmother who holds real social power and is the one who saves Cinderella. The evil, ugly stepsisters aren’t punished, but turn over a new leaf and are forgiven. They’re also not ugly or necessarily evil to begin with — softening the villainization of stepfamilies that plagues many fairy tales. The prince’s role in chasing Cinderella, after being seduced by her beauty and grace, is downplayed by the actions of the Queen — a strong character who spends the evening with Cinderella and facilitates their marriage. And what I love the most about this story is that Cinderella is recognized for her piety, patience and humble nature — and not necessarily her beauty.

Gorgeous and magical visuals provide the medieval Andalusian backdrop, and include cultural elements from both North Africa and Islamic Spain. Also woven throughout the story are quotes from the Qur’an and hadith, and themes relating to worship during ‘Eid ul-Adha.

Cinderella herself is extremely pious. She prays, fasts, reads Qur’an, and wears hijab — but these religious elements are not presented obnoxiously, which is my usual complaint about Islamic children’s literature. Her story is tragic and the balance between her struggle and her faith doesn’t seem out of place. If Cinderella decides to recall Qur’anic verses when she’s forbidden from attending Eid prayer, it’s further proof of her strength of character.

Author and teacher Fawzia Gilani-Williams was born in England, currently teaches in the UAE, and has one daughter. She was gracious to give me some time out of her busy schedule to answer some questions about her reasons for writing this story.

wood turtle: Why did you decide to become a writer?

Fawzia Gilani-Williams: I didn’t make a conscious decision to become a writer although my father would encourage me to write. I liked to write and as a teacher I did a lot of writing especially in the Islamic schools I worked at because the stories we used in English were ones in which Muslim children were invisible. I never came across characters that my students could identify with. So I wrote for them or I adapted stories while I read to them.

In 2002, Eid coincided with Hanukkah and Christmas. When I walked into the public library, which is required to give equal visibility to all children, there were attractive and beautifully displayed books for children on Hanukkah and Christmas and also on Kwanzaa which I didn’t know much about. Eid is the second largest celebration in the world and there was nothing for the Muslim child. This was my springboard to write Eid stories and that’s mostly what I’ve written although now I’m working on the Islamic Fairy Tale Series.

wt: What inspired you to write an Islamic alternative to the classic tale?

FGW: As a child I loved reading fairy tales. But when my father began to follow Islamic teachings, I saw where some of the fairy tale heroines did not behave or dress in a way that could be reconciled with Islamic teaching. I recall little Muslim girls frowning at Cinderella’s gown. They didn’t think Cinderella was a nice girl. Later I’d written an Islamic version in the late 1990s for my students but it was quite different to this version.

As a teacher I know the importance of a Muslim child having a sense of place and of being able to identify with heroic characters that love God, are caring, helpful, patient and have big, strong hearts. Muslim children need to have their way of life validated in books. They need to see that their way of life represents the best of humans like Abraham, Moses, Jesus and Mohammad, peace be upon them. Certainly research shows that when children don’t see themselves in books, it’s a huge concern.

wt: Could you tell me a little about why you chose to create strong female characters and not only an Islamic tale, but a seemingly feminist one?

FGW: My intention was to portray Cinderella as a practicing Muslim. Her actions and thoughts needed to be in harmony with Islamic values. Having a strong heart is a virtue we want to encourage in children. Sadly Muslim children live under a dark bullying and unkind media cloud and have to defend their beliefs. Muslim children have to be strong so they can respond in the best and most courteous of ways to the false propaganda that is said about Islam.

If a feminist reading of Cinderella can be seen, it is because Islam is feminist in the sense that God Almighty empowered girls and women with rights. When I learned about the rights of Muslim women through the books my father gave me, I was astonished.

wt: Is there anything else you’d like to share with our readership?

FGW: Inshallah that the most beautiful duas are for them and I send my salaam.