The news here in Quebec – and in many other parts of Canada – has been flooded in the past few weeks with stories about the newly-proposed Charter of Quebec Values. Formally announced on Tuesday, September 10 (although some details had been leaked a couple weeks prior), the charter, if eventually passed as law, would prevent people working in the public sector from wearing “conspicuous religious symbols,” including headscarves, face veils, kippas, turbans, and large crosses. Framed as a way of ensuring a secular and religiously neutral state, the charter would apply to jobs including civil servants, teachers, professors, judges, police officers, daycare workers, healthcare workers, and many others. For those wanting to know more, this article gives a good overview of what the charter would and wouldn’t do, and this translation of a Manifesto for an Inclusive Quebec is a good summary of the main things with the current proposed charter. It is currently open for “consultations” (defined in a pretty flaky way; you can call them or leave a message on their website), and the government has announced that it will be formally proposed as a bill in Quebec’s provincial parliament sometime this fall.

It took me a few days to think through this enough to write anything at all that wasn’t full of ranting and raving. I have a bunch of thoughts about this, but to be honest, my main reactions are anger and frustration. This policy, if it becomes law, will have huge material impacts for a number of minority groups in Quebec, while reinforcing narratives that privilege only one group as the “we” of Québécois identity, and increase suspicion and marginalisation of Muslims and other minority religious communities. By some accounts, this has already started; one woman was recently verbally harassed for wearing hijab, and her son was spat on and hit. This is not to say that Quebec – or anywhere else in the rest of Canada – was perfect before this charter was proposed, but the news is nonetheless infuriating and incredibly discouraging to those of us living here.

But here’s my attempt at an actual analysis – with pictures, because apparently we’re all about visible symbols in Quebec these days.

Exhibit A: Inventing religious symbols to make us feel better

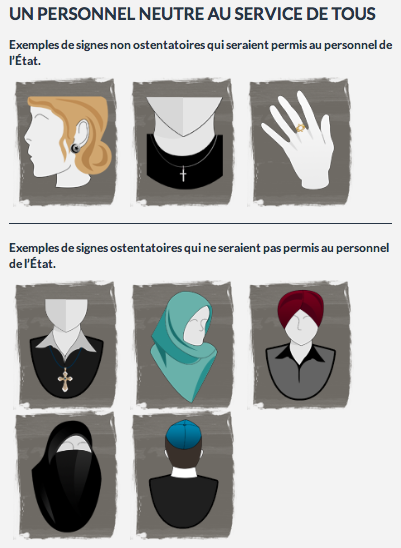

This is a graphic put out by the Quebec government as part of the charter proposal, to show us which “religious symbols” will and will not be acceptable under the new charter. Hijabs and niqabs, along with turbans, kippas, and large crosses, will be banned for those working in the public sector, while small, “non-ostentatious” symbols like a small cross, a ring with a star of David, or earrings with stars and crescents, will be allowed. The most obvious problem with this is the completely false equivalency between a headscarf and something like a cross necklace (where the former is understood by many as a religious practice and even an obligation, whereas the latter may indeed be simply worn as a religious sign); letting people wear small religious symbols is really not a helpful substitute for the clothing that is being banned. Not to mention that I have never in my life seen star-and-crescent earrings. I realise that it’s just an example that they’re giving of an acceptable size, but it’s still a pretty strong symbol of the government’s ignorance (and/or complete apathy) that they’re suggesting replacing clothing that has really deep religious resonance for many people with pieces of jewellery that they pretty much made up.

Exhibit B: Taking a role in people’s religious practices in the name of religious neutrality

Articles like this one, which states point blank that Quebec should, in fact, impose its culture on others, make it clear that the headscarf is the primary religious symbol targeted by the charter, at least in the minds of many of its proponents. The women pictured here, wearing headscarves and holding Quebec flags in the protest against the charter this past Saturday, are clearly oppressed and in obvious need of rescuing, right?

In the past few weeks, various news sources have included articles, interviews, and letters by Muslim women and others living in Quebec, many of whom were born and raised here, about how the proposed charter would affect them. It’s these women who, if the charter passes, will be denied the chance to work as teachers, doctors, or civil servants, unless they take off their scarves. When the government representatives talk about getting rid of religious symbols in order to preserve the “neutrality of the state,” it’s people like these women who will be affected, and bodies like theirs that will be left out of the image of the state created within the new charter and “our values.” And in the process, the state – instead of separating itself from religion – is inserting itself into the religious decisions of its individual citizens, claiming that that it knows better than that do which clothing they should be wearing, and telling women that they are not welcome to work in this province without removing certain articles of clothing. This is neither a religiously neutral nor a pro-woman charter.

Exhibit C: But REALLY big crosses are totally cool

This is the crucifix that hangs in the National Assembly, Quebec’s provincial parliament:

And this is the cross on top of Mount Royal, in the middle of Montreal:

These? Are staying. Quebec’s “cultural heritage” apparently trumps the religious resonance of these particular symbols, so the government sees nothing wrong in keeping one cross in the very place that government decisions are made, and another on top of a really high point in Quebec’s biggest city, where people can see it for miles.

So, in other words, a ten-centimetre cross worn around someone’s neck might be seen as too ostentatious, but a 30-metre cross lit up at night on Mount Royal is somehow not a conspicuous religious symbol at all. And a person wearing a turban or headscarf can’t possibly be neutral, but the crucifix in the National Assembly, which was put there in 1936 precisely to symbolise the strong relationship between the parliament and the Catholic Church, is absolutely no threat to the religious neutrality of the state.

Personally, I don’t have strong feelings either way about the crosses themselves, but these contradictions are really hard to swallow, and they make it hard to take seriously the claims that this is really about neutrality. It also says quite a lot about who has the power to deem their own religious history as “part of our heritage” and thus supposedly neutral, while certain ways of dressing are seen as only ever religious and necessarily threatening.

Exhibit D: Defining “us” and “you”

This is an ad, put out by the Quebec government as part of this whole “values” kick, that recently appeared in a metro station in Montreal; I’ve seen variations of it popping up around the city. On the left panel, certain religious books are acknowledged as sacred, and on the right, gender equality and religious neutrality of the state are acknowledged as sacred too. It’s not that I disagree with these points, obviously, but given that these ads are being linked to this particular charter, there’s a suggestion wearing visible religious clothing necessarily puts you outside of these sacred values. The bottom left of the right panel says “Un Québec pour tous” – “A Quebec for all.” It’s pretty clear who is actually being referred to as part of this whole, and who Quebec might not really be “for” after all.

There will, no doubt, be many other images and actions on all sides in the next few weeks. For the moment, it is clear that there is much at stake in the questions of who has the power to define the meaning of religious symbols, who gets to say that they truly belong here in Quebec, and what this will mean for Muslim women.