A JOYFUL NOISE

A JOYFUL NOISE

Reflection on

Encountering

the Psalms as

Spiritual Practice

A Sermon by

James Ishmael Ford

6 January 2008

First Unitarian Society

West Newton, Massachusetts

Text

O come, let us sing unto the Lord: let us make a joyful noise to the rock of our salvation. Let us come before his presence with thanksgiving, and make a joyful noise unto him with psalms. For the Lord is a great God, and a great King above all gods. In his hand are the deep places of the earth: the strength of the hills is his also. The sea is his, and he made it: and his hands formed the dry land. O come, let us worship and bow down: let us kneel before the Lord our maker. For he is our God; and we are the people of his pasture, and the sheep of his hand. Today if ye will hear his voice…

Psalm 95:1-7

The other day I was speaking with a colleague who teased me about my biographical blurb at the Society’s website. What seemed to tickle her, way beyond necessary, I thought, was how I was described as a “social justice activist.” Knowing me rather well she observed that other than working for marriage equality in the Commonwealth and sitting on various boards dedicated to good things, “you seem more about sitting in silent meditation and organizing retreats than standing on picket lines and organizing protests.”

I fear I blushed. And it seemed my suggesting how contemplation informs and sustains social engagement only evoked a smirk from my friend. I should probably say so-called friend. Since then I’ve been thinking a lot about this and today I’d like to share some of what I’ve thought about the place of contemplation, meditation and prayer, the whole of the inner quest, within our liberal religious communities. And from that a little bit about how we might engage spiritual practices.

First, this probably needs underscoring. I’m absolutely not suggesting we put off acting in the world. We need to reach out to others every step of the way, as we begin this spiritual path and as we mature on it. How that reaching out might best happen is rich and complicated and is the subject for a different sermon.

Here I want to address what I believe is the foundation of our common lives. Now over the years I’ve come to believe several things about the spiritual life. The first of these is pretty well summarized in that line attributed to Jesus in John’s gospel. I quote it in my preferred childhood King James translation, chapter three verse eight. “The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, and whither it goeth: so is every one that is born of the Spirit.” That is the spirit goes where it will and rests where it will when it will.

A bottom line of the spiritual journey is that we can’t control it. The recent revelations of Mother Teresa’s life-long doubt and general lack of spiritual experiences confirming or consoling her in the life of sacrifice she chose is telling. If anyone can earn those moments of consolation one might think it should be she. What Teresa got is a deafening silence. I find this very important and I’ll return to the silence of God in a bit.

The truth is spiritual practices don’t guarantee spiritual experiences, or at least the experiences we think we should get. Rather, our encounters with the spirit are more like being hit by a runaway bus. And our spiritual practices just make us accident-prone.

When these accidents will come, we can’t say. And, where they take us to, we can never predict. Perhaps you’ve heard the joke about how the pope called his cardinals to Rome for an important and urgent meeting. They moved quickly and within two days all of them who were able to travel gathered in the Sistine Chapel where the pope announced, “I have good news and bad. The good is that Jesus has returned. We haven’t met yet, but I’ve spoken to him on the phone.” There was a long silence. Finally one of the cardinals stood and said, “This is wonderful news, your holiness. What possibly can be bad about that?” The pope sighed and replied, “He was calling from Salt Lake City.”

Spiritual practices, creatively engaged, open us to moments of surprise, shift our worlds and allow us to change. That’s the miracle of our disciplines. I think. I feel. Deeply. And whether the shifts are conscious and come as gifts of grace and consolation, or we never actually sense the shifts; what I’ve seen all around me, is that people who give themselves over to the practices, in fact do change. And as we hope to be of use in the world, to work for justice, to be better parents, to be decent human beings, that opening to change is absolutely critical. So, I suggest, our consciously engaging spiritual disciplines really is important.

One of the joys for us as Unitarian Universalists is that we’re open to many different possibilities for our spiritual practices. In fact I suggest it is prudent to look widely, not only to find our own right path, but also within that wide looking we discover how we open our hearts and find ourselves more tolerant, and better able to glean the real lessons to be found in our disciplines as we choose them, and settle into them.

As my taunting colleague suggests I’m rather well known in our small circle as someone who has delved fairly deeply into the practices of Buddhist meditation. I’m particularly devoted to the Zen discipline of zazen, seated silent meditation. But today I want to reflect a little on a more traditional western practice and suggest it might be a good UU practice. Today I want to hold up for your consideration, if only briefly, as an example from our common culture, the way of the Psalms.

As a child I loved the fact that I could always quickly find the Psalms in my Bible. In the King James Version, which we believed was written in the language of Jesus himself, if you hold the book in both hands and simply open it at the middle, it should open to the Psalms. Pretty cool, certainly seemed so when I was ten.

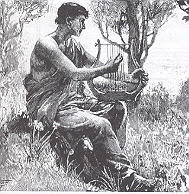

They are attributed by tradition to David, the “sweet singer of Israel.” There are 150 of them in the traditional Masoretic text, 151 in the Septuagint the standard Greek version. The arrangement is a little different depending on whether it’s Jewish, Orthodox Christian, Roman Catholic or Protestant. But the gist is the same. And from pretty much the beginning the Psalms have been used for contemplation and prayer. They inform the spirituality of both Judaism and Christianity. Among the Jewish community, the whole of the psalms might be read in either a weekly or monthly cycle, by individuals or in groups. A similar rhythm has been a pattern of prayer for the Christian church, and has continued down to our Puritan and congregational ancestors.

Earlier, I made a passing reference to God’s silence. I’ve mentioned this once before, but I think it’s important to recall here. When I was an adolescent, having been raised a Baptist but wracked by doubts, more than doubts actually, my fervent prayer to the unknown god was for he or she or it to manifest to me in some tangible way. I even offered a deal. Reveal yourself and then kill me. I meant it. Absolutely meant it.

In response I got nothing but silence. In reaction to that silence was a journey that included a bit of time as an angry atheist, studying with Hindus, becoming a Zen monk, studying with Episcopalians and Gnostics and Sufis. And eventually becoming a Unitarian Universalist. And finally from that, becoming, of all things, a UU minister. All through this journey for me that prayer continued in constantly mutating ways. I came to know that silence intimately. I delved deeply into it. I came to treasure it. And at some point I discovered that silence itself spoke to me.

God speaks. But, it turned out, not in the way I wanted, or rather in the way I thought I wanted. The revelation of God as love and joy, yes. But, also, it turns out God manifests as some very terrible things, or so it seems. I can never forget the story of Robert Oppenheimer witnessing the first atomic blast at Alamogordo. As many here know Oppenheimer was also a Sanskrit scholar, and as he witnessed that great and terrible event could only think of that passage from the Bhagavad Gita where the prince Arjuna begs the god Krishna to reveal himself in his full glory, only to be granted that vision. As they say, bad move. “If the radiance of a thousand suns/Were to burst at once into the sky/That would be like the splendor of the/Mighty one…/I am become Death,/The shatterer of Worlds.” Or, maybe, it wasn’t a bad move.

My encounters with the Psalms are rather like this. And I’ve given it some serious attention, in the time after I left the Buddhist monastery following a version of the Psalter, that is a collection of the psalms, for almost two years. It was disconcerting, difficult, boring, offensive, and kept opening doors.

The voice that speaks out of the psalms certainly is not entirely nice. Beautiful passages like that haunting lament beside the waters of Babylon ends with a wish to have the head’s of enemy baby’s crushed against rocks. I recall an Episcopal priest who once excused herself from a meeting saying she had to prepare to conduct the “ancient war chants” service. She meant lead Evening Prayer with its collection of psalms. In the Psalms we encounter that shatter of worlds, in it we hear the voice from the Whirlwind.

The practice is to encounter the psalms over and over again, to sit with them, to reflect on them, to pick at them, and to allow them to sit with us, to reflect on us, to pick at us. My friend and colleague Christine Robinson has sat with them, read the many translations, and has come up with her own versions. I encourage anyone thinking of these as a spiritual discipline to consider such a thing for your self. We do this and sometimes there is nothing but silence in response. And sometimes the silence roars out, and if we’re lucky we’re shaken to the core, we find ourselves much bigger than we thought, and we get a hint of why and how we should act in the world. Here I find the sustaining possibility for a life worth living.

So here again, the 95th Psalm, which was our text for today. Let me read it here in the poetic rendition of Norman Fischer, those first seven verses:

We are here Singing to you Erupting into shouting At the place of the rock of our salvation Coming gratefully and gracefully before you here Affirming with our words, the music of our mouths That we are possessed by you, yours entirely For you give us the gift of sovereignty A power above all others The majesty of our absolutely being You whose hands touch the earth’s depths Whose heart pierces the mountain peak The always changing sea is yours for it exists because of you And your hands have formed the firmness of the lands So we come in awe, offering the earth and sea of ourselves to you Bending what we are toward you, shaper of us For you are our beyond and we are your doing Sheep who graze in your pastures, animated by your hand If only we could awaken to it! The voice out of the silence. And, I believe, the sustaining possibility of every action in this world that counts. It is the call of a deep love and our response. This is what I feel spiritual practice is all about.

Amen.