THE ART OF CONVERSATION

Reflecting on Spiritual Practices Within Liberal Congregations

James Ishmael Ford

5 October 2008

First Unitarian Church

Providence, Rhode Island

Text

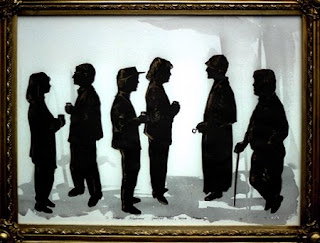

Long ago, a rural village in Japan decided to build a temple and invite a Buddhist monk to come and minister to them. There were two applicants who seemed qualified, so the village decided to put them to a test in order to determine which one would be their new spiritual leader. In the middle of the village two gigantic iron pots were set up and a fire was lit under each one, bringing the water inside to a boil. Then the two applicants were asked what they would do with the pots to prove their worthiness. The first monk was an advanced tantric meditator. Without batting an eye, he calmly climbed into the first pot, which reached up to his neck. Unaffected by the boiling water, the monk meditated for hours. The villagers were amazed and impressed – here was a monk who truly had amazing powers. The second applicant was a Shin priest (Shin, not Zen. If Zen is more like Unitarian, you could think of Shin as more like Universalist. This is a really rough analogy…). He didn’t have impressive robes like the tantric monk, and he didn’t even shave his head. Everyone wondered how he could possibly do better than the first man, especially since while the tantric monk had been quietly preparing himself for his intense meditation, the Shin priest had just been chatting casually with the villagers, asking about their families and how the harvest was going. But when his turn came, the Shin priest gave a big smile and walked up to the second boiling pot. “Quick!” he called out. “Bring me some vegetables and salt!” Puzzled, the villagers gave him what he requested. Whistling to himself, the Shin priest chopped up the veggies and threw them in the pot with the salt. After a while he called out, “Soup’s ready!” He served the whole village supper from the big pot, and talked with them late into the night about their hopes and fears, offering advice and telling them to take comfort in Amida’s never-abandoning compassion. In the morning, the villagers thanked the tantric monk for coming and asked the Shin priest to stay and minister to their village.

Jeff Wilson “In the Pot,” from his forthcoming book Buddhism of the Heart

Forrest Church, Unitarian Universalist theologian and until his declining health recently forced his resignation, minister of our All Soul’s church in Manhattan, laid out the question, the question when he observed, “Religion is the human response to the dual reality of being alive and having to die.” This dual knowledge is the gift of our humanity, and it is our curse. We live within that tension. We are alive. It is sometimes awful, sometimes glorious, and always precious. And somewhere along the line, sooner or later, we will absolutely, without any doubt, no matter what anyone may tell us to the contrary, we, that is you and I, will each of us, die.

Some of us have become rather skillful at avoiding this point, and so the concerns of religion may play lightly in our lives. A very few of us can ignore these questions right up to our death. Denial is a powerful force in the human heart, and not without value. But, most of us, somewhere along become aware of that tension. And so, sooner or later most of us find the questions of life and death, of religion, of spirituality as deeply personal questions. With that we begin a quest to understand, to seek meaning. And, my goodness – where that quest might take us! I look at my life and I shake my head at the peregrinations of a contemporary quest for spiritual insight.

There’s an old story, I no longer recall where I first heard or read it, but since that time I’ve run across several versions. I think pretty much all of them begin in Brooklyn. One day out of the blue Sadie says to her closest friend, Frankie, “It’s time to go to India and see the Guru.” Her friend was taken aback.

Frankie tries to dissuade her. In one version the friend says, “But it’s a long journey. And what will you eat? The food’s too hot and spicy. You can’t drink the water; you can’t eat fresh fruit or vegetables. You’ll get ill. Plague, cholera, typhoid. God only knows. Can you imagine? And no Jewish doctors. Why torture yourself?”

But Sadie persists. She obtains a plane ticket, she flies to New Delhi, she takes a train, then a bus, then hires a car, and finally, finally makes her way to the ashram where the guru lives and teaches. It turns out even in this remote location there are a lot of people who want to see the guru. She’s told the line could take three days. She doesn’t hesitate, she agrees and waits.

Finally, as she gets to the door the attendant says whatever question she has for the guru must be framed in no more than three words. Sadie says that’s okay, and finally she’s ushered into the room. She looks at the guru, a thin man with long black hair and a thick beard sitting on an elaborate throne-like chair. He looks at her, great kindness in his eyes. And she says, “Marvin, come home.”

I have at least two take aways from this story. One is that the spiritual quest may take us across the globe, and I think we really need to be open to the many ways people have found depth. The other is that no matter how far we may travel, no matter how deep our immersion, at some point we have to come home.

I know how on my own spiritual path, even though I found a pearl of great price in the Zen traditions, at some point I also felt a need to come home, to find a Western spiritual expression for my life. At some point I discovered my mom insisting I do so. If not literally, she actually was much too circumspect to ever actually speak a word. But moms occupy our very being and whispering from somewhere in the back of my brain she did call me home. I felt even though the deeper points were universal the Asian trappings were not mine, somewhere along the line it all had to find a Western expression.

Eventually that led me into a Unitarian Universalist congregation. The truth is what I found was rather light on spiritual practice, at least in the formal discipline sense of that term. I’ll return to this. But first just a little about what I did find that made me stay. I found a community of people with a deep tradition of rational religion, that is religion tested through the fires of the mind, who had created a democratic spiritual community, concerned with finding ways to nurture and support each other, to raise children with wide hearts and deep minds, and to reach out to the world and help.

Now, becoming UU worked for me so well for a couple of reasons. Zen is a powerful discipline, but also Zen as a practice in the West was pretty much a personal discipline. The organizations, other than for monasteries, were pretty much put together on a school model. You came, did your practice, and left. So, each, for me, filled a part of the whole I needed. I found doing Zen and Unitarian Universalism was like putting crunchy peanut butter and strawberry jelly together. Just perfect.

In the quarter of a century that has passed since that time, increasing numbers of Unitarian Universalists have become acutely aware of a need for spiritual disciplines. That tension of being alive and knowing we’re going to die just inclines people that way. We have folk who faithfully engage TM, Yoga, Zen, Insight, Tibetan practices, just to begin the list. However, I’m pretty much convinced importing Eastern disciplines will be the happy solution for only a minority among us. I think most of us who desire spiritual disciplines will need to find a spiritual practice in some sort of Western context. Could be prayer, a very important option, it might be found in the Western Gnostic or Earth centered traditions. But, today, I want to explore how it might be Small Group Ministry.

Originally Small Group Ministry was pitched to me as community building, which it is. And, it was pitched as a way to grow churches; something dear to minister’s hearts, but which it doesn’t seem to be. However as I sat in a trial group I thought to myself, there’s something big here. Then I listened to people talking about what happened to them over time. And I knew from my years of spiritual discipline this was one, as well.

Let’s return briefly to today’s reading. I rather enjoy the fact this traditional Japanese story has such close similarity to our European story “stone soup.” I savor those moments of parallel evolution, when we stumble upon them. But there’s another point. There are many different paths and the ones that work for me are the ones that are predicated in the assumption the world we live in is enough.

I suggest, with plenty of room for individual variance, in general, practices that work for us as Unitarian Universalists are going to be simple and this worldly, about cooking veggies rather than withstanding boiling water. Practices that pull us to pay attention to this world, this body, this mind, right here, right now, are the ones most consonant with our traditions as Unitarians and Universalists.

And that’s Small Group Ministry in a nutshell. It takes our UU proclivity to talk, and in general we UUs love little more than the magic of words, it takes talking and makes it a spiritual discipline. What’s not to love there? We gather into small groups, nine or ten or twelve people, occasionally fewer, rarely more, and we covenant to come together regularly. Then when we gather we engage in a highly structured conversation on a theme. Usually this theme is established through a study sheet that contains a few paragraphs of materials, a quote and maybe a question or two to consider. The subject may be God or death or mother or water. There’s an endless supply of themes. But, the conversation is constructed in a way that no one can dominate, and to which all are expected to bring themselves as honestly as possible.

As I like to observe, well maybe I don’t like it, but it’s true; when I’m speaking only one ninth of the time even I cannot spend the rest of the time thinking about what I’m going to say next. At some point one must begin to listen. And that’s when it becomes a spiritual practice. I like to call this practice the Art of Conversation. But, given the built in time constraints, in reality, it is the Way of Listening. This is a spiritual discipline.

Let me unpack that phrase spiritual discipline, just a little. First, “spiritual.” For me the meaning of that word is found within its etymology. It comes from the Latin spiritus, meaning “breath.” Similar usages are found around the world. The Hebrew ruach, the Greek pneume, the Sanskrit prana, and the Chinese chi all derive from their language’s word for breath and each stands for that deepest thing in human life, that which gives life, that which gives meaning. The spiritual enterprise is about life and meaning. Spirituality is the task that arises out of our knowing we are alive and knowing we are going to die.

Now, here’s the real bottom line. Let’s be frank. In the last analysis life itself is the teacher. One could say life is the only teacher. Some of the wisest people I’ve ever met wouldn’t know a spiritual discipline from a dog’s bite. Some of the deepest, kindest, largest hearted people I’ve ever met would never darken the doorway of a church, temple or synagogue. Life was their teacher, and they paid attention. And without a doubt it was enough to find the deep moment that transforms lives.

Let’s talk just a moment about that finding, about what is found whether on one’s own or within a spiritual discipline. Birth-right UU, and Buddhist scholar, Jeff Wilson, who wrote the book from which we derived today’s reading, in that book quoted Ludwig Wittgenstein saying, “I believe the best way of describing (my deepest experience, that life-shifting experience) is to say that when I have it I wonder at the existence of the world. And I am then inclined to use such phrases as ‘how extraordinary that anything should exist’ or ‘how extraordinary that the world should exist.’”

If we are gifted with spiritual insights, they come to us something like that. How extraordinary! How wonderful! That’s the turning heart into awe. How sad and how beautiful! When we find that moment we discover the boundaries between our individual lives and the life of the world begin to dissolve. And, further along, we notice the boundary between that moment and the rest of our lives begin to dissolve. And somewhere along the line we notice we are vastly larger than we had previously dreamed.

And, I suggest, finding this insight is worth a great deal. It brings a certain peace to us as individuals, and it can inform how we encounter each other. So, rather than just hope life teaches us, and wait, some of us take the bull by the horns, and add that second word, “discipline.” We take on the disciplines of spirituality, like those found in Small Group Ministry. Of course, there is no guarantee in this spiritual work. Those precious moments of insight, they come to us out of the blue, sort of like being hit by a bus. But, spiritual disciplines make us accident-prone. As such they’re worth a lot of effort.

As we wind down here, I hope you’ll indulge a few thoughts on how we might dive deep with Small Group Ministry, or frankly, any other spiritual discipline. Jeff Wilson’s book, which I’ve cited, I think, twice now, is in the last stages of preparation for publication. I’d been sent a manuscript with a request if I liked it would I write an endorsement? I liked it, a lot; I think it’s wonderful. It addresses Shin, a school of Buddhism I know little about but which I keep encountering, and which increasingly I realize I need to know more about. But, for our quickly running out time here, one thing Jeff addressed seemed just exactly to our purposes.

It turns out that Shin’s principal spiritual discipline is often called Deep Hearing. And, when describing what this meant, I felt Jeff was describing what you and I might find in our own Small Group Ministry encounters as a Way of Listening. Admittedly, I’m slightly adapting what he offers. If you want the original, you’ll have to wait on the book, which will be coming out soon from my publisher, Wisdom Publications. The title is Buddhism of the Heart.

There are three stages to this practice of deep listening as we might encounter it in our Small Group Ministry. The first arises as we listen to each other hopefully, believing if only hesitantly that there is something larger to encounter, and that our friends’ words may take us in that direction. It is a kind of faith, which as UUs, and knowing our friends, it can be hard for us. But we don’t need a lot of faith, just the most tentative faith in the possibility of finding something deeper, something truer than we have right this moment. And this is the magic invitation: if we engage the conversation with just this bit of hope, then doors are thrown wide open.

The second stage happens when we walk through the door, as that hope drops away and we simply listen. Just listen. Just this. In that just this, just listening, we find a powerful moment. It is a surrender into what is, letting go of our stories. It is a letting go of trying to be in charge, or thinking we’re not good enough, or whatever the demon is we usually like to go to the dance with. As we just listen, it almost doesn’t matter what is said. We find an intimacy that is the opening of our hearts, and the discovery of a larger life.

What is lovely is it doesn’t stop there. The third stage is where the two things are integrated as one, where hope returns but floats in the background, kind of our personal theme music, the pulsing current of life itself. At some low level it permeates our listening, but at the same time we are just listening. Here we find something lively, a dynamic that shifts who we are, that genuinely changes our lives.

From this place we discover a moral compass that can inform how we relate to others, the people we meet in that group, our families and friends, and beyond that everyone and everything in the world.

As easy as pie. And as difficult as can be. But it is the way home.

And, I really believe, worth every minute…

Amen.