A Few Words on Zen Practice

10 October 2011

Jan Seymour-Ford, Senior Dharma Teacher

Practice Leader, Benevolent Street Zendo

I’d like to say a few words about our practice together, and why it’s important.

Lately there’s a crew of folks who are training to become chant leaders. If you’ve arrive a few minutes early for our sitting period, you’ve probably seen us here. It’s lovely that so many people who are willing to serve the sangha.

Boundless Way Zen has a strong lay perspective. That’s largely a heritage from our Harada-Yasutani lineage. The great gift of this is that it’s a way of living the Dharma that complements our lives here in the west. I won’t elaborate on the history and background of Buddhist monasticism, which is the norm in Asia. Attempts to import that reverence for and insistence upon monastic life along with the teachings of the Dharma creates difficulties, because we don’t have a heritage of supporting monasteries here in the West.

Boundless Way Zen has a rebel streak to it, which it gets from two sources. One of our grandfathers in the Dharma, through the lay-oriented Harada-Yasutani lineage, is Robert Aitken. He dedicated his life to the Dharma and was never a priest. His Dharma heir, my first Zen teacher, is John Tarrant, who is also most decidedly not a priest. The second source is the strong influence of Unitarian Universalism. Three of our four Guiding Teachers are UUs, so even if you have never heard of Uuism, it is influencing our practice – non-liturgical, strong emphasis on democratic principles, and questioning authority.

The great gift of this rebellious streak is a fresh questioning, testing the teachings against our own experience, and lively, empowered sanghas. So what’s the shadow? Rejecting formalism also has its consequences. Sometimes it tips over into anticlericism and a sweeping rejection of much of the form of our tradition.

Over the years, and also very recently in this room, I’ve heard sangha members say that they have no affinity for the liturgy, and even find it off-putting. I hear you, because I used to be one of these people.

So why is it important to chant sutras together? Why does it matter how we hold our hands, how many times we ring the bell, and which way we turn? Over the years, the liturgy itself has taught me why it’s important. I’ve discovered three reasons:

For the first, here’s a Joko Beck’s version of a Zen story from her book, Nothing Special:

A student said to Master Ichu, ‘Please write for me something of great wisdom.’

Master Ichu picked up his brush and wrote one word: ‘Attention.’

The student said, ‘Is that all?’

The master wrote, ‘Attention. Attention.’

The student became irritable. ‘That doesn’t seem profound or subtle to me.’

In response, Master Ichu wrote simply, ‘Attention. Attention. Attention.’

In frustration, the student demanded, ‘What does this word attention mean?’

Master Ichu replied, ‘Attention means attention.’

If you’ve sat zazen for five minutes, you’ve probably asked yourself this as we’re sitting: “Is that all?” Yep! The Dharma always brings us back here to the preciousness of this fleeting moment of life. Everything we do, every moment, is a teaching that reminds us to be present, to pay attention. When we pay attention to the detail of the liturgy we’re expressing our gratitude and reverence for the Dharma and training our minds to be present and attentive.

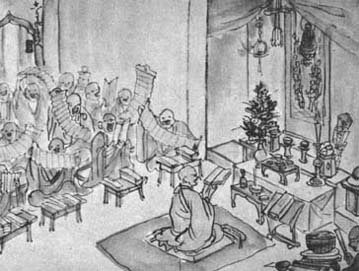

The second great gift of our liturgy: when we chant together, we’re actually embodying the teachings. We breathe the teachings together, we’re being the teachings together. In this practice, breath is the anchor of presence and attention, and chanting the sutras is a way of experiencing the teachings right down to our cells.

The third great gift of our liturgy: it reminds us that this is a group practice. When we do this together, we’re embodying the teaching: “all beings one body.” I especially treasure the awareness that practioners have been chanting some of these teachings and bowing together for hundreds and hundreds of years. When I practice as a member of the sangha, I’m reminded that it’s not about me. It gives me an opportunity to put aside my narcissistic perspective and experience that connection with the Buddha nature that pervades the whole universe.

And finally, I’ll share this experience. Melissa Blacker is one of the Guiding Teachers of BWZ. At one of our very first multiple-day retreats, about ten years ago, we were introducing the oryoki meal ceremony. I was the only individual familiar with the method of serving food. Melissa needed to learn it, so I told her to watch how I did it. Afterward, she said I didn’t do anything the same way twice. I was really stung, because I really did my best to be attentive and consistent! But as hard as I try, I simply don’t remember the details of the very well.

So don’t worry, we’re very merciful to screwing up! The point is not to get it right! The point is experience the gifts of attention and embodiment and connection with all beings.