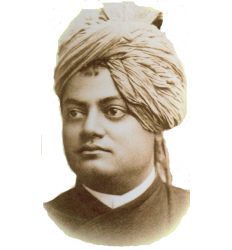

Swami Vivekananda and Unitarian Universalism: A Footnote

Swami Vivekananda and Unitarian Universalism: A Footnote

James Ishmael Ford

A few years ago I had the privilege of preaching at the First Unitarian Church of Oakland, in California. Among the mix of reasons I was so pleased to be standing in that pulpit was how I felt a connection like a current of electricity to the great Swami Vivekananda who had stood in that very same pulpit something more than a hundred years earlier.

Swamiji was an important figure in my own spiritual development. What for a very long time I was only vaguely aware of, was how important he also was to Unitarians and Universalists at the time of his visits to the West, an importance that may continue down to this day.

There is no doubt Swami Vivekananda’s visits to America were watershed moments in interreligious encounter. In 1893 he captivated the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago and from that moment drew large crowds wherever he spoke. He introduced America to the idea, startling at the time, that a non-Christian and a non-European could be both saintly and scholarly, and could advocate another religious perspective as compellingly as any Christian preacher. And for some hearing him, much more compellingly than what they’d heard before. Swamiji heralded a spiritual revolution in the West.

As a Unitarian Universalist I can take pride in the fact that while the swami may have given talks to one or two small groups earlier, his first real public talk was at the Annisquam Universalist Church, in Gloucester. Within the week he gave his second talk to a significant audience at the East Church, 2nd Congregational, Unitarian, in Salem.

During his time in the West he would speak at many houses of worship as well as at secular halls. Significantly, however, during Swamiji’s two visits to America he visited Unitarian and Universalist congregations and spoke at them some twenty-seven times. In addition he spoke another four times at a Unitarian congregation in London. In aggregate he spoke at vastly more liberal churches than at the churches of any other religious tradition.

And some of these were the most prominent congregations of the two denominations that encompassed liberal religion at the end of the nineteenth century. He preached in Chicago and Detroit and Minneapolis, at a number of churches in New England, in Pasadena and in Oakland.

Oakland seemed to be particularly significant for him. He preached at the First Unitarian Church of Oakland in 1900. According to Swami Nikhilananda, “Swami Vivekananda journeyed to Oakland as the guest of Dr. Benjamin Fay Mills, the minister of the First Unitarian Church, and there gave eight lectures to crowded audiences which often numbered as high as two thousand.” Having been to that church, I can’t imagine how they fit so many into the building, and I understand they used every available space. At one talk it was estimated five hundred people were turned away.

In the following years his memory was particularly cherished within the congregation. Two pictures and several plaques memorialize his visits, and a chair is preserved with the unlikely story of his having been carried around in it. Rather more likely is that he sat in it while it rested firmly on the ground. What is more important is how his connection to that chair had made it so special to his memory in that congregation.

The admiration and attention to this meeting of traditions in Oakland continues among the Hindu and particularly within the Vedanta communities in America, and the church is frequently visited by swamis and others seeking places clearly marking this remarkable teacher’s visit here.

During these visits Swamiji also met some of the leading lights of the liberal religious communities. Before the Parliament began, as the guest of Kate Sanborn in New England, he first was introduced to her cousin, the remarkable Franklin Benjamin Sanborn. Sanborn was a Transcendentalist, intimate friend of both Thoreau and Emerson, a fierce abolitionist, in the years running up to the Civil War a supporter of John Brown, and one of the “secret six.” And this would simply be the beginning of his connections to prominent Unitarians and Universalists, often those at the cutting edge of religion and culture. Among them Swamiji would meet with Unitarian reformers Jane Addams and Julia Ward Howe as well as the Reverend Jenkin Lloyd Jones, one of the leaders in the trend leading Unitarianism away from its Christian roots.

At first the subjects of the swami’s talks were non-controversial, touching on culture and encouraging tolerance. Gradually however, he began touching on more important themes. Swami Vivekananda believed the rift between rationalism and spirituality that marked religions in modernity created a wound that needed to be healed. And, as he wrote in the Absolute and Manifestation, there was a healing balm for those with ears to hear, “the Advita of India, Non-Dualism, Unity, the idea of the Absolute, of the Impersonal God.”

And there is one more thing. When Universalism first emerged as a theological perspective within American Protestant Christianity the questions turned on whether a good God would or even could condemn anyone to eternal hellfire. Both Universalists and Unitarians embraced the universalist rejection of damnation.

However, by the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries this liberal religious tradition began to reinterpret the term “universalism.” The new view, the one now current in the successor denomination to these traditions, the Unitarian Universalist Association is that there is a universal current within religions, and that all faiths share in the spark of truth. Anyone familiar with Vedanta knows this is essentially the same view as preached by Swami Vivekananda.

My small speculation is that while much of what would become this contemporary Universalism was obviously influenced by own homegrown Transcendentalism, itself clearly influenced by the new availability of religious texts from the world’s faiths, including the Bhagavad Gita, there is also the unavoidable fact that the remarkable Swami Vivekananda was meeting Unitarian and Universalist ministers and thinkers and preaching in Unitarian and Universalist churches to an educated and questing community. And in these meetings and talks he was sharing a universalist message that would become nearly the same as what was soon to be preached from these liberal pulpits.

The precise connections? Who knows. But I find Swami Vivekanda’s possible influence on a critical theological view we both share a tantalizing thought..