A Meditation on Bodhidharma’s Way and Ours

James Ishmael Ford

3 February 2012

Boundless Way Temple

Worcester, Massachusetts

Be patient to all that is unsolved in your heart

And try to love the questions themselves,

Like locked rooms and like books

That are written in a foreign tongue.

Do not now seek the answer,

Which cannot yet be given to you

Because you would not yet be able to live them.

And the point is, to live everything.

Live the question now.

Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it,

Live along some distant day into the answer.

Ranier Maria Rilke

I no longer recall when I first heard the verse. But, somewhere early on it became the great pointer for me, an invitation to something I didn’t fully understand, but which I fully desired.

A special transmission outside scriptures,

Not founded upon words and letters;

By pointing directly to one’s heart mind

We see into our own true nature and attain Buddhahood.

It was sung to us by Bodhidharma, it was sung directly into my heart, it was a beacon that I followed, a distant light in the fog, the north star guiding me across the great ocean.

And, I no longer recall precisely when I learned that Bodhidharma never spoke these words. The four-line verse has no older textual foundation than the early twelfth century in the Collection from the Garden of the Ancestors. Which is, what, six hundred years give or take after the old monk died?

Whatever turmoil that roiled within me, fortunately I also realized the deeper truth continued, the pointer was right, we don’t rely upon texts, however rich and wonderful they may be, we look within and without, making as few judgments as possible, and in that find who we are. Our way is dynamic and has taken shape within history, just as it should.

I’ve long realized that what makes this way so important for me is the reality that if every Zen practitioner were killed and every Zen word written were burned, immediately after people would realize the way and describe it in terms recognizable by our ghosts. The mutability of Zen’s history was just one more bit of evidence that the reality does not lie in ink on paper, or even words spoken, although and there’s the wonderment of it all, they also do contain it.

As I grow older and find myself delving into the traditional texts with the eyes of what a generation or two ago would very much have been considered an old man, and even in our time, getting there, I find it like reading letters from a lover from long ago. The words touch my heart, even the lies comfort me, and the truths, the truths I find ever clearer. I continue to find new lessons, new pointers each useful in the ways I need them to be to direct my life as it is today to deeper insights, more healthy perspectives, and ever richer possibilities.

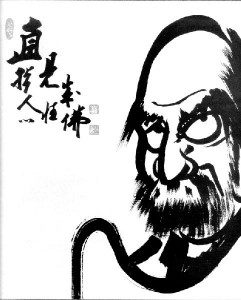

Of late, I find myself returning to our ancestor that red-bearded barbarian, who didn’t sing the song, but did, really did; that song which caught my heart and directed my life’s course. It turns out the oldest textual reference to a Bodhidharma is found in the Records of the Monasteries of Luoyang, dating from the middle of the sixth century of the Common Era. According to the scholar John McRae this Bodhidharma is a fairly stock-figure foreigner whose main purpose is to witness to the grandeur of Luoyang’s monastic establishment. The first reference we get to someone generally recognizable as the founder of our school in China is found in the mid-seventh century Further Lives of Eminent Monks, a sequel to the Lives of Eminent Monks compiled roughly a century before.

This is a very important text. While many of the details that will flesh out Bodhidharma’s story as the second of the three founding myths of our way, following the story of the Buddha’s awakening and prior to Huineng’s “autobiography,” are not yet in place, some important terms are introduced, such as “wall gazing,” skillful means,” and “putting the mind at rest.” This biographical sketch also cites and even outlines “The Treatise on the Two Entrances and the Four Practices,” which, as you know, we’re reflecting on throughout this intensive practice period at the Temple.

At this point it is impossible to say who actually wrote “The Treatise on the Two Entrances and the Four Practices,” although it has been published under Bodhidharma’s name since the second half of the seventh century. His principal disciple Huike has always been associated with it, and some argue he compiled his teacher’s message as the treatise, which was then later edited more or less into the document we have by the monk T’an-lin. I find it interesting that all other texts attributed to Bodhidharma, in the consensus view of the scholarly community are of much later date. So, if there is a Bodhidharma teaching, this is it, including from pretty near the beginning “wall gazing,” “skillful means,” and “putting the mind at rest.”

Among the things that interest me about this document is how it stands in the place of our Zen orientation. The Dharma as we receive it in the Sutras is highly didactic, laid out in order, and formalized in stages each spelled out. Within this the anecdotes of awakening turn on the Buddha explaining things clearly and people realizing the truth of his teaching. Ta da!

Zen as we practice it, particularly within the koan introspection disciplines, plays out differently, as you may have noticed. Particularly if you try to get some simple from point “a” to point “b” instructions. Instead of lists and stages, stories are told. Sometimes with directions in them, but often even a point is hard to discern. We are, instead, each of us, invited to look within our own hearts, into a rich but also desolate place, a jungle or a desert, or a deep frozen mountain range. And as we trek all along the way surprises, shocks, offense and joy erupt, pretty much unbidden, often at the strangest moments, and from those moments, we pick ourselves up, dust ourselves off, and, strangely, mysteriously, our lives take new courses.

Now are these approaches different or the same? I suspect the answer is yes, different and the same. There are stylistic differences, no doubt. That’s pretty obvious. But, there’s something else to this document. If you’ll pardon the metaphor which shouldn’t be pushed too hard, we find a shift from a left-brain encounter that is more analytical that characterizes much of classical Buddhism to a right-brain experience that is more intuitive and is very much characteristic of the Zen way as we normally encounter it.

Here in this treatise we start with an invitation to the leap from the hundred-foot pole. But, most of it is within that older more formal didactic expression of our heartful way. If you don’t push it too hard, the treatise is sort of a platypus, part mammal, part reptile, part classical Mahayana Buddhist explanation, part Zen presentation. You get to choose which is mammal, which is reptile. But all of it, I suggest, alive, and, for our purposes, useful.

That said the first two or three or four reads, I didn’t really like the treatise very much. As one friend pointed out, every paragraph is open to misunderstanding. Not to put too fine a point on it, it is possible to read the instructions to include “believe what you’re told,” “blame the victim,” “hate your life,” “don’t care,” and “give us money.”

I prefer the pure Zen version of Bodhidharma who we get in the first case of the Blue Cliff Record, with rough and ready encounters, direct pointing to the matter at hand and throughout a deep call to not knowing as the way to the end and the end, itself, surprises like volcanoes, bubbling, waiting to erupt into our lives.

Of course that’s all taste buds. In fact the invitation is really the same, classical Mahayana or as the way of surprise, two ways to the same place. First we’re offered the Zen way in through the teachings themselves, as they are. Here, the great principle, the Dharma fully present, here, now.

Here we’re called to believe, not in the dead letter sense of affirming that which we know isn’t so, but rather as my friend the scholar Joan Richards says, believing as loving, belief as experience, as an act of surrender into something joyous and intimate. Not someone else’s experience, but yours, but mine. Believer, lover, this is a dangerous path, no doubt. And it is good to check out that which you’re going to surrender your life into before going too far. It is surrendering our idea of separate selves as permanent and abiding things. And instead, it is opening ourselves as wide as the sky, and including it all as part of our interior landscape.

Just step off.

And if that is too hard, well, there’s another way that is the way, stages for the heart’s opening. It comes out of a contemplation of the classical teachings. And it’s a pretty clear roadmap. It involves paying close attention to the mysterious actions of karma not in our lives, but as our lives.

Personally, as someone who stands in the liberal camp, that doesn’t hold the need to believe in literal transmigration of lives, in contemplating the guidance found in the treatise, I’m delighted and informed to see how absolutely the doctrine works in this life of many lives.

Here we’re invited to surrender to the realities of the flux of events, and out of that to learn the dance of relationships, to see into the reality that we are, all of us, boundless, our essence is no essence at all, just openness, and from there to realize our lives just as they are, when not clung to, are the Dharma, the dharmakaya, the great open itself. No difference.

Step one, step two, step three, step four.

And then what?

Like that Tarot card, with all the vigor and foolishness of youth, looking to the sky and stepping off the cliff. Like that person who has made it up to the top of the hundred-foot pole, only to discover there is still that next step, away from the pole. Off the cliff, away from the pole. Looking, not looking. No rules, or following the guidebook.

The invitation ultimately is one thing, breathing, living, inviting.

However you got there, however you got here.

Step out.

Into those five hundred lives as a fox.

Into the way of true passion: wholly, holy, present without clinging to any particular story.

Stepping out into our true lives.

Just this.

Only this.