BY THE WATERS OF BABYLON

Longing, Denial, Murder & Dreams of Homeby

James Ishmael Ford

29 April 2012

First Unitarian Church

Providence, Rhode Island

Text

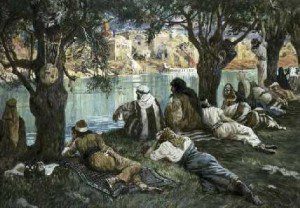

By the waters of Babylon, there we sat down, and we wept when we remembered Zion. In the midst of it all we hung our harps upon the willows. They that carried us away captive required of us a song. They wanted us to sing of joy. “Sing to us,” they demanded, “one of the songs of Zion.” But how shall we sing the Lord’s song in this strange land? If I forget you, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget its skill. If I do not remember you, if I do not hold Jerusalem as my chief joy, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth.

Psalm 137 1-6

Today we’ve received more members into this thriving community of hope and promise. For some it will prove a way station on a longer spiritual journey. For many this will become the place of exploration and depth, where the promise of fulfillment can be found, a genuine spiritual home. And so, wherever we are on our various paths, today is an invitation to consider that journey, and our home, what might be our true home.

The one hundred thirty-seventh Psalm dates from the Babylonian captivity, somewhere in the sixth century before the Common Era. This is a very important moment in history. What we have there is a small community of intellectuals and craftsmen part of that mix of people living in what we today think of as Israel and Palestine who when their land was conquered had been carried away to Babylon.

Who they really were is complicated, and further complicated by the contending myths of peoples who claim that land today. But, for our purposes here let’s call them Judeans. It’s hard to say how much they thought of themselves as a separate people from their neighbors in that land before this time. But during that captivity something happened, a spiritual alchemy, a distillation of more ancient fables and stories into a holy book containing a more or less coherent history and, even more important, a promise. During those years birthed much of what we have come to call Judaism.

All brought together in a dream of home, of separation, of exile and a promise of returning to that home. And so it has always been. Whoever we are, wherever we’ve come from, that story of being lost and found, that’s always ours, as well, isn’t it? Do you notice how it lives in your heart?

It does seem most of us are not settled, are not at home. We have different ways of saying this, smaller, larger. A popular one here is to listen to a sixty year-old ponder what he thinks he’ll do when he grows up. But there are more serious ways of speaking to that sense. Somewhere within our hearts there is always a sense, which whispers, which calls to us in our dreams. In the midst of whatever conditions we’re caught up in, we feel this urge, this need, this longing of our hearts.

And, as natural as this is, without our attending to this movement of our heart, we find ourselves lost. This is true for individuals, and it is true for peoples. This longing is one of the most powerful currents of our hearts. And when not tended to in healthy ways, it will emerge in very dangerous and sometimes terrible ways.

So, this past Tuesday, the 24th of April marks the ninety-seventh anniversary of the beginning of what the Armenian people call the Great Calamity, and what the rest of the world calls the Armenian genocide. That terrible event visited upon a small nation is sadly, part of a litany, possibly, probably endless, of people bringing terror and death to their neighbors. The Jewish holocaust in the 1940s was the most notorious bead on this string of deliberate and systematic destruction of a people, of a culture, justified because they are the “other,” and therefore are a threat whose destruction offsets the basic morality of every culture. Sadly, there are nearly endless examples.

Thus it has been, thus it is. More recently we have Rwanda and Srebrenica. Glaringly, our own American history is marked by the genocide of the Native American peoples, together with slavery one of the two original sins resting a rot at the foundation of our nation.

I find myself considering the Armenian genocide in particular, and how it is denied. We have a similar problem here in how many are not willing to consider the genocide of the Native American peoples, as well. I suggest this is one of the most dangerous things we can do for the health of our hearts, for the possibilities of change. We need to not turn away.

Indeed, that is the nut at the heart of it all. Today I want to reflect on the nature of our longings, remind us of how dangerous it is to ignore them, to not attend to the currents of our hearts. And, also, to share a word of hope, to say what comes with attention, in our bringing full presence to what is.

No doubt our human minds and hearts are complex things. Events happen and we order them, we give them meanings. At the very center of this is the mystery of our human memory. What we give our attention to and how we shape it creates the narratives of our lives, tells us where we come from and points to where we can go.

An example. My people are the Irish. While my direct ancestors came here at the turn of the last century almost certainly fleeing poverty, the majority of my people came to this nation fifty years earlier, fleeing something even worse, the great hunger. There’s a memory. Fleeing horrors, we came to a country that was reluctant to accept us. Within the mad rush forward of course we wove stories about ourselves. Some of these were useful, others, not so much. For many the stories were little more than maudlin inspirations for tin-pan alley. Green beer once a year is a sorry remembrance of a lost nation.

Other memories were of past deprivation and oppression and out of those came dreams of new hope and possibility. Irish Americans are second to none in our patriotic fervor for our adopted nation and the opportunities we claimed. And, and this is an important point. What we weave together as our stories are always mix of truth and fantasy. And what we deny or forget may be just as influential on future events as that which we remember,

Which raises the other issue for us to struggle with, also deeply connected to memory. That is place. What is home? Where is home? In addition to those more ancient homelands, do you come from the rocky soil of New England? Perhaps the plains of the Midwest? Or, like me, that far country of teeming cities clinging to rugged coasts, high mountains in the distance, and a moderate climate? For each of us, no matter how far away our lives may take us, these places have a permanent part in our hearts, and of who we are.

And, in that sense of where we come from, we also have that ancestral homeland. Germany? England? China? Japan? Armenia? And what if our ancestors were kidnapped? There are those in this Meeting House who know that bitter question. Where in Africa? Where? Or, what if you know, but if you go to that place and there are only a few stones piled upon each other for you to touch and to recall how your people were shaped, and lived? What if that homeland is now a place where the songs of your ancestors are no longer sung? I think of the native peoples of this continent.

And, this is the greatest mystery of it all, the one that must inform every other thought we have: at some point we’re all connected, deeply, truly. One family. We are all bound up in these acts of memory and loss, of place loved and taken. These are not empty words: the harm done one, is harm done to all. If we hope to act with grace in this world, if we hope for peace in our own lives, for joy, for authenticity, we need to remember all this; and we need a place to put our feet.

So, back to memory. Back to the power of presence.

People often, I believe, misunderstand the call to presence, to notice this place, to stand here. A person who cannot take memory into this moment is not fully present. And, that’s not the end of it, either. We need to have the cascade of hopes and fears for the future living in our hearts, as well.

This is how it can be so complicated. The one hundred and thirty-seventh psalm, so lovely, so compelling in its dream of captivity and longing for home, has a line at the end, of wish for vengeance on the captors so terrible that it is always cut from the reading. I suggest turning away even from these dark dreams of vengeance is a mistake. We need all of it.

But, we need it not be the end point. Not the end of our song. We need to never forget the Armenian genocide, never forget the murders of the Jewish people, never forget the killing of so many Native American cultures. And the consequences of those things. We need to not turn away.

If there is no memory, and no thought of the future, then there is no present. Not really. Not in a way that counts. Not in a way that allows the pregnant possibility of our existence to come forth.

And living into that possibility is the task at hand. What does it mean to live full, to be fully present?

I find as I consider the great sadness of the Armenian genocide, along with all the other horrors and indignities perpetuated upon people, great and small, I feel a sense of loss that I have trouble describing to you here today. But when we don’t turn away, when others deny, but we know in our hearts, found through presence to what is, the vastness of our true home, things happen. And within that I feel some sense of hope, some sense of that birthing of possibility as presence itself, shining, fully visible.

Because, and here is a great secret. This place here is our home. All those places that dream in our hearts, and which we should never forget, bring us in their own good time: here. To this place. To this moment.

This is our home.

And this seems to be our call. We must remember. To forget is to collaborate with those thieves of the heart who would deny what we have been and what we might yet become. But if we do remember, however much the world changes, we will find a place to stand.

And it is here. To be here fully, to bring it all together is to throw open the gates of paradise. This is our true home.

Finding that longing. Knowing that longing. Dreaming that longing. And bringing it here. This is the great healing. This is coming home.

Amen.