So, what is Dharma transmission in Zen? We know there is a transmission lineage that claims a succession from the Buddha down to any number of people. It doesn’t take a lot of historical research to see this idea was birthed in China and is heavily influenced by the Chinese idea of family and familial inheritance.

At the same time it stands for something, or some things that remain compelling to many people on the spiritual path. As a practical matter Dharma transmission is the only constant marker of proficiency in the disciplines that birthed within the Zen schools. It has also been the way institutions have marked out leadership by both inclusion and exclusion. Nonetheless, William Bodiford in his essay on “Dharma Transmission” in Steven Heine & Dale Wright’s Zen Ritual: Studies of Zen Buddhist Theory and Practice, suggest that in addition to continuing the Chinese familial character of transmission, that “it is inherently flexible and multidimensional, so that no single criteria always exists in every case.” In North America this mutability certainly is true, and with a vengeance.

In 1703 the Soto school laid down two criteria, that there be no more than one transmitter and that the ritual be conferred face-to-face. In America both of these fundamental categories have been challenged, each with different consequences.

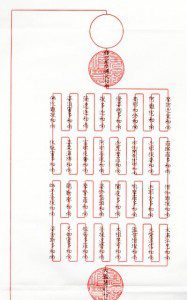

Many Zen teachers claim more than one transmission, including myself. Usually this involves Soto priests who study koans and receive a second transmission in that koan line. Still, at this time, the traditional transmission documents convey a single line and a single transmitter, with the interesting exception on many Soto documents where both of Eihei Dogen’s transmission lines are recorded. Beyond the Dogen lineage I’m aware of no one who has incorporated multiple lines in their transmission documents.

One way the fact of multiple transmissions has been dealt with among some Soto teachers is that the three traditional san matsu documents are received with the original Soto teacher, and a second ceremony, sometimes with a fourth document are given that may or may not include a lineage chart of that second teacher. Some refer to the first ceremony as Dharma transmission, and the second as Inka shomei, a term adapted from the Rinzai school.

As to the second issue at variance with the practices of the Japanese Soto school, at least one Soto teacher is ordaining, although he has not to date transmitted anyone, via ceremonies conducted online. He argues this is in a face-to-face ceremony. That said the Soto Zen Buddhist Association board after consulting the membership sent a letter to the membership in May, 2012, saying such ordinations and hypothetical transmissions would not be registered with their organization, with the caveat that exceptions might be allowed in extreme circumstances such as a deathbed ordination, and then only after consultation with the SZBA board. As one might expect other teachers will begin doing similar online ceremonies, I suspect the last of this has not yet been heard…

Also, there are increasing numbers of Zen teachers and priests functioning outside the bounds of the normative institutions. In a pattern similar to the epsicopi vagantes movement within Catholic Christianity, involving people who can (usually) claim a transmission, but who lack the depth of training that is normally required in the contemporary western Zen world.

For instance, the American Zen Teachers Association, the other nationwide organization of Zen teachers, attempted to define who is admissible to their organization. As there is considerable overlap between the AZTA and the SZBA this may be a helpful. They ask applicants how many days of retreat that person had completed prior to authorization as a teacher. While there is no hard and fast rule, it appears no one has been admitted to AZTA membership who has not had at least three hundred days of intensive meditation retreat experience, most with more, five hundred days being common. How a “day” is defined is not precisely clear, but a good faith assumption is from early morning until evening. It is assumed this is a supervised retreat with a guiding teacher. I’ve encountered transmitted teachers and priests at the edge of the movement with fewer than a hundred days of retreat. It is perhaps also helpful in understanding what this means to note that in Boundless Way Zen one hundred days is the minimum pre-requisite for novice ordination. (I should add there are instances of healing this apparent breach, and people who start out at the “edge” eventually are brought into the mainstream through additional training.)

This all should show the questions of how Zen teachers in the West are prepared, and to what purposes precisely remains open. Still, some outlines are appearing.

Lots and lots of supervised zazen does lie at the heart of this preparation. However, what beyond this is not clear. Many feel a significant monastic experience is necessary. While the specifics of Zen monastic training in Japan are not exactly replicated here in the West, there are training centers that come close in their exacting discipline. However, increasingly the training is home based with regular retreats of three, five or seven days, and which take place over ten to fifteen to twenty years prior to authorization, often with little and sometimes no monastic experience at all. Most communities have become clear that a certain level of academic training is also necessary. Teachers and priests should understand their history and the mainstreams of Buddhist thought. Additionally a number of Soto groups have re-introduced koan introspection practice, mostly through a reform curriculum developed by a Japanese Soto master who completed koan practice with several Rinzai teachers and then modified the curriculum to honor the Soto inheritance. This is usually a central feature, although not an absolute requirement within our Boundless Way community.

Additionally, precisely what Dharma transmission itself is has broken open with various understandings being offered around North America. Within the rhetoric of Zen it has everything to do with enlightenment. But enlightenment is a slippery term with no single objective criteria. And, whatever else may be true, it also has to do with being part of a community of practice for a substantial amount of time, and is a marker of seniority within that community. And perhaps this more modest goal should be held up as equally important to the less tangible sense of awakening. As important, I quickly add, as some sense of awakening is – and, for me, personally, necessarily verifiable through the quasi-objective koan curriculum.

Additionally, in Japanese Soto Zen transmission and ordination have been joined since sometime after the establishment of Soto in that country. Zen teacher Dosho Port speculates possibly no more recently than a hundred or so years ago. I suspect longer, but do not know when. This collapsing of ordination and transmission occurs nowhere else in Zen’s history.

In China ordination had to do with the creation and transference of merit. Lay people giving gifts to the ordained, particularly by way of support, created merit. This is important because as the Zen way came to Japan, in the Soto school ordination and transmission were collapsed together. And clerics became the professional practitioner, and where lay people while theoretically able to do the practices, in reality, rarely did. Much of Zen’s discipline became vicarious, done on behalf of the larger community by this clerical class, and accessed through ceremonial transference of merit, even generations after ordination did not mean embracing celibacy.

In the west this aspect of the clerical and lay distinction has become meaningless to the majority of Western Zen practitioners. In fact in most practice communities the actual distinction between lay and cleric is uncertain, other than most clerics shave their heads and most lay people do not. Each as pretty much the same access to training and increasingly both have access to a reclaimed transmission independent of ordination.

But for the most part even yet, in Western, North American Soto Zen it is clerics who are charged with the guidance of centers and practitioners.

Such is the state of Soto Zen in the West. Here what I find is that transmission is mostly a marker of a certain level of training, the confidence of a specific teacher who has given her or his name as confirmation of that individual’s ability, that becomes the gateway into the guild of Zen teachers.

And that it should or at least can be a marker of insight is important to me. But, even that insight needs to fit within the life of community, not subordinant, but woven together.

That said, more is needed. At least I find this so. But what precisely, is not clear.

And so the conversation continues.